CHAPTER 1.0 INTRODUCTION

Note: Significant components of this chapter come from Stopher et al.’s (2008) NCHRP Report Chapter 1 and Tierney et al.’s FHWA Manual Introduction (Cambridge Systematics 1994). Other key contributors are Peter Endemann, Kara Kockelman and Charlene Wilder.

Travel is core to human activity, for personal and commercial reasons, of individuals and freight, over short and long distances, via motorized or non-motorized modes. As traveling populations and their communities evolve and adapt, transportation challenges have become more complex. Combating congestion, noise, emissions, loss of life, and other concerns while developing sustainable and reliable transportation systems and facilitating relatively low-cost travel is a tremendous task. Good data is fundamental to this task.

Appropriate solutions to transport and traffic problems require more holistic approaches than have often been pursued in the past, recognizing the complex interdependencies of economies and transport, population and mobility, spatial structure, landscape and environment. A solid sense of a population’s preferences and travel patterns is an indispensable ingredient in the planning, design, and management of transportation systems, at local, regional, national and international levels. Constrained budgets and great uncertainty in future conditions present challenges to the transportation profession, and travel data acquisition and analysis is one of the few low-cost ways of helping ensure more cost-effective solutions, robust to variations in preferences, prices, climate, technology, and other uncertain features of tomorrow’s terrain.

Several decades ago, the travel demand modeling field developed primarily to anticipate the demand for major changes in transportation infrastructure, such as the addition and expansion of freeways and rail systems. In the United States, the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments (CAAA), 1991 Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA), 1998 1998's Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21), and 2005 Safe, Accountable, Flexible, and Efficient Transportation Equity Act (SAFETEA-LU) have evolved to expect more detailed inputs for policy studies. The planning process must now provide a variety of specific values for air quality analysis, evaluation of non-highway investments and transport policies, and support of integrated regional and statewide transportation improvement efforts. New demands on travel demand models include anticipation of congestion pricing impacts, details of trip timing and peak spreading, greenhouse gas emissions, non-motorized travel choices, emergency response, and freight movement, among other behaviors. The Transportation Research Board's Special Report on Metropolitan Travel Forecasting (TRB 2007) concludes that there is a need to improve the state of metropolitan travel forecasting and that the data used in such models are lacking or questionable. In particular, there are insufficient data for model validation (especially relating to non-work travel) and a general lack of data on goods movement. A need for better travel data is a common issue, throughout the world.

The contents of this extensive Travel Survey Manual emphasize one of the most important aspects of transportation planning, demand modeling, and policy-making: the travel survey data. Such data are used to anticipate the future, calibrate and validate behavioral models, and inform a variety of policymaking efforts. Current transportation planning models rely to a great extent on the disaggregate behavioral travel data obtained from travel surveys for establishing trip generation, trip distribution, mode split, trip scheduling, vehicle ownership, tolling response, and other important relationships. Of course, the next generation of travel models will also rely extensively on very detailed household level analyses (Shunk 1994). In fact, given the level of detail required by the newer, activity-based and/or microscopic models of travel choices, the data demands will likely be greater - in terms of route choice and location reporting details. Fortunately, technologies such as GPS-enabled data loggers are helping moderate respondent burden while providing higher-quality data free of many errors of the past, as discussed later in this Manual.

1.1 Background

Personal travel surveys have been conducted for over 40 years, but during that time no attempt has been made to standardize the process or to institute consistent practices of acceptable quality or reliability. Two TRB conferences -“Household Travel Surveys: New Concepts and Research Needs,” in 1995 and “Information Needs to Support State and Local Transportation Decision Making into the 21st Century” in 1997 (TRB, 1996 and 1997) - and NCHRP Synthesis of Highway Practice 236: Methods for Household Travel Surveys (Stopher and Metcalf, 1996) emphasized the need for improved standardization in survey data collection. The contention is that standardization of the survey process can lead to efficiencies in the planning and execution of surveys, in the assessment of data quality, and in the comparison of data between one metropolitan area and another.

Over the past 40 years, many millions of dollars have been spent on collecting household or person-based data for transportation planning. For most metropolitan areas, the largest routine expenditure made from planning budgets is for the conduct of household or person travel surveys. In 1996, it was reported (Stopher and Metcalf, 1996) that the average survey cost was $400,000 for consultant services for the conduct of household travel surveys. Assuming that only half of the approximate 350 Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) in the United States conduct travel surveys within any decade, this represents a total expenditure of $74 million in a decade, or about $7.4 million per year. In spite of this huge level of activity and expenditure, there is no consistency in the process of executing surveys, nor are there recognized procedures for assessing the quality of the end product. Nevertheless, even larger sums of money are subsequently spent on developing and using travel-demand models based on these data and in investments into major capital projects, implementation of far-reaching policies, and other related decisions.

In some cases, the metropolitan regions that commission travel surveys do not have staff with in-depth knowledge and experience in that field. As a result, some MPOs are unable to make informed selections of consultants to perform surveys and are also unable to assess whether a useful product was obtained. Subsequent work in using the data for situation descriptions and modeling often reveals serious flaws in the data that could have been avoided if there were either a sufficient availability of expertise at the MPOs or a set of clearly defined procedures that could be followed by an MPO in guiding the process, selecting consultants, and assessing the work that was done. Some consultants who undertake such work are unaware of the difficulties involved in data collection and lack knowledge and expertise in various aspects of collection and assessment. In addition, the MPOs that may select consultants also may lack basic knowledge of specific aspects of data collection and assessment. They could also benefit from a set of standardized procedures and measures that would aid them in determining the type of survey to undertake, the methods to be implemented, and the means to assess whether the survey was satisfactorily executed.

It has long been determined by most metropolitan regions that data collected in one region has little relevance to another region. While there is no doubt that there will be local contextual issues that may make transfer of data difficult or inappropriate at times, the major reason for this perception is that each household travel survey is usually sufficiently different in design and execution from any other survey, resulting in comparisons from region to region that are completely obscured by methodological and implementation differences. If consistent procedures were applied in the collection of such data, many of the apparent differences between regions may disappear. In addition, there are often slight variations in question phrasings that are sufficient to introduce major barriers when comparing data; appropriate standardization could remove these barriers. This could also lead to a greater willingness of regions to borrow data from each other, and thus reduce the overall necessity to expend so much on collection of new data. It would also help the recognition and capture of travel among regions and, of particular importance, enable comparing local to national surveys.

The issue of standardizing personal travel surveys was investigated in this study. This involved reviewing past practice, conducting analyses on data sets collected in past travel surveys, conducting new travel surveys, identifying individual aspects of personal travel surveys that potentially could be standardized, evaluating these candidate procedures, and then compiling a set of recommended standardized procedures. The execution of this process is documented in the following pages. Forty procedures in travel surveys are recommended for standardization in this study. An additional 20 were identified for possible standardization but were either considered to be less important than those selected or beyond the scope of the project. Included in the report is a sample Request for Proposals (RFPs) to assist metropolitan areas in commissioning travel surveys that are consistent with the proposed standardization.

1.2 Purpose of This Manual

This survey manual provides transportation planners with guidance for developing and implementing the most common types of travel surveys, including:

- Household Travel and Activity Surveys – Surveys that are used to track the travel behavior of households within the study area, generally employing journal methods.

- Vehicle Intercept and External Station Surveys – Surveys of auto travelers entering or leaving the study area, or crossing key screenlines within a study area.

- Transit Onboard Surveys – Surveys of transit passengers conducted as they travel.

- Commercial Vehicle Surveys – Surveys of taxi and truck owners, operators, or dispatchers designed to track commercial vehicle travel within the study area.

- Workplace and Establishment Surveys – Surveys taken at places of employment to develop trip attraction measures.

- Special Generator, Hotel, and Visitor Surveys – Specialized surveys designed to describe travel by visitors, and travel to and from special trip generators such as airports.

- Parking Surveys – Surveys of auto travelers parking in specific locations or parking lots within the study area.

- Web Based Surveys – Also effective for those not reached by other methods.

- Also, Stated-Response/Stated-Preference surveys, GPS-supported Surveys, Longitudinal and Panel Surveys, and a number of other specialized techniques to enhance data and results.

The first set of travel survey guidelines was published by the Bureau of Public Roads in the 1940s (Highway Research Board 1944). The guide was updated in the mid-1950s and again in 1973 (U.S. DOT 1973, U.S. DOC 1954). Because there have been radical changes in the transportation planning environment over the last 20 years, and as the field of commercial marketing research (and its application to transportation issues) has rapidly improved in the last decades, many of the specific data collection techniques described in the 1973 guide have been supplanted by more efficient and cost-effective procedures.

In this Travel Survey Manual, we assume that the user of this manual has recognized the need for newer or different, disaggregate data, and that the need for survey research of some kind has been defined. We also assume that the user of this manual has developed a detailed modeling plan and has a strong understanding of the data requirements for the anticipated models. This manual does not address transportation modeling explicitly.

1.3 The Benefits of a Travel Survey

As noted earlier, travel surveys are highly meaningful in the context of the design and management of transportation systems and policies. Data applications address a wide range of issues, including traffic forecasting, transportation planning and policy, land use connections, system monitoring and benchmarking, and other important areas. Presently, transportation planning models lack the spatial and temporal detail, the behavioral sensitivity, and sensitivity to alternative modes of trip making needed to provide the forecasts required by current regulations in the United States and abroad. Policies impacting vehicle purchases and retirements, mode and destination choices, route selection, carbon and other emissions, and travel scheduling cannot be developed or ultimately evaluated without data - data that allows for robust estimates of traveler behaviors and, later, data describes actual choices. Some examples of data applications are described below.

In the context of the transportation-land use connection, Siedentop et al. (2005) used the 2002 German National Travel Survey to analyze the influence of spatial structures on travel behavior across metro areas1, and Nobis and Lenz (2005) examined the role of gender. South Africa’s National Travel Surveys contribute to what are termed “Key Performance Indicators” for land passenger transport, as required by national legislation and policy (Department of Transport 2005). Using the United States’ 1985 National Household Travel Survey, Cervero (1996) examined the travel benefits of locating retail facilities close to residential areas. Endemann and Muller (2000) have studied the potential of transit-oriented developments, in terms of reduced automobile reliance. A recent three-wave household survey in Perth, Australia seeks to estimate mode shift along a new planned rail corridor (Olaru and Curtis 2007).

Provision of local transit is another topic requiring high-quality data. In general, on-board surveys are used to understand current use and anticipate future use of existing and new lines, while also distributing resources and revenues (Sommer et al. 2008). German and South African National Travel Surveys are used to identify opportunities for transit markets (see, e.g., Department of Transport 2005, Endemann and Maleika 2005 and Follmer et al. 2004). The German Mobility Panel revealed patterns in public transport use across days and over years by recording participants’ mobility patterns over multiple days, in many cases making use of data tied to monthly travelcards (Dähne and Reinhold 2008, Zumkeller et al. 2005).

The UK National Travel Survey and the Swiss National Micro census are meaningful examples of repeated cross-sectional surveys (up to every five years), offering information across regions while monitoring mobility over time (Chalasani 2005, Bonnel and Armoogum 2005). The German System of Representative Travel Surveys is conducted every five years in several cities and provides insights on mobility indicators across distinct locations. Urban and regional entities benefit from add-ons to Germany’s national sample, allowing comparisons in mode splits among target populations (INFAS 2004). Such benchmarking is an explicit objective in South Africa’s National Household Travel Survey too (Department of Transport 2005). Clearly, there are many travel surveys in regular use around the world, offering value for local, regional, national and international comparisons and policymaking.

1.4 Emerging Issues for Travel Surveys

The newest generation of travel surveys is especially challenging for planners because the surveys need to obtain more and better data for modeling purposes in a time when survey research is becoming increasingly difficult to conduct. Typically, agencies are hard-pressed to assemble the required levels of resources (funding and manpower) necessary for implementing new survey data collection efforts because of competing transportation planning requirements. However, the need for the data continues to grow. New regulations, new aspirations and new tools mean that current and future surveys must provide more detailed data on a number of subjects that previous surveys did not cover. The original travel surveys collected data on how people traveled, including number of trips, choice of destination, and choice of mode. The new modeling requirements dictate that travel surveys not only provide more detail on how people travel, but also yield behavioral information on peoples’ choices of whether, when, and how they would travel under certain conditions. The new modeling requirements have led to the collection of the following types of data:

- Vehicle Characteristics and Usage Data – In recent surveys, respondents have been asked detailed questions about the vehicles that are available to them and about vehicle usage for each trip. This information is being used for many purposes, including analysis of the cold start/hot start phenomena in air quality analysis.

- Nonmotorized Travel – Unlike many of the earlier travel surveys, new travel surveys are asking respondents to provide information on walking and bicycling trips. ISTEA requires that these modes be considered in mode choice models.

- Activity-based Travel Diaries – Some recent travel surveys have collected diary information on activities requiring and not requiring travel. These data will be used to develop activity-based models and to evaluate how people choose between activities requiring travel and other activities.

- Time-of-day of Travel – In response to the need for peak and off-peak travel modeling, newer travel surveys are asking more detailed questions about people’s choices of travel times.

- Stated Response (Stated Preference) Exercises – Historically, travel surveys have recorded actual respondent behavior, or respondents’ “revealed preferences.” Some recent travel survey efforts have also sought to predict the effects of new policies and travel options for which little revealed preference data are available. These efforts usually rely on exercises that ask respondents to make hypothetical decisions involving multiple attributes or parameters.

1.5 Survey Trends

In addition to the changing transportation planning requirements, travel surveys are also being greatly affected by changes in the market research and survey field.6 Travel surveys exist in the wider world of marketing research, and to properly design a travel survey effort, analysts must consider both the transportation planning outputs of the survey and the practical survey-related issues involved.

In his recent review of data collection methods in the U.S., Lysaker noted a number of recent trends in the commercial surveying field. Although this review did not focus specifically on travel surveys, the general marketing research trends are applicable to the travel surveying practice. The key trends in travel surveying over the past several years in the U.S. include:

- Declining respondent cooperation rates;

- Increasing analytical demands on the survey data; and

- The use of new survey technologies, such as computer assisted interviewing and geographic information systems (GIS), to improve survey efficiency.

The net effect of these trends is that travel survey efforts have become substantially more complex than in the past.

1.6 Declining Cooperation Rates

In the past several years, the percentage of potential respondents refusing to participate in surveys has increased. Researchers attribute this trend to a number of factors. First, the proliferation of survey efforts has caused a general feeling of antipathy towards these efforts in a number of people. Almost all potential survey respondents are likely to have had some firsthand experience with being asked to respond to surveys on some subjects. If the experiences were unpleasant for any reason, the potential respondents are likely to balk when asked to consent to another effort, regardless of the subject matter or the survey sponsor, public or private.

In addition to being asked to participate in surveys, potential respondents are also bombarded with the results of various surveys from the media. Many of the results that are reported are contrary to the preconceived notions of potential respondents or turn out to be invalid. For instance, some political polls taken shortly before an election predict the wrong outcome. Many respondents conclude from these events that the inconsistency is the fault of the survey, and they generalize this finding to surveys. Therefore, when these people are asked to participate in surveys, they do not see any reason to do so.

Another important reason for declining cooperation rates is that most of the survey techniques in use today are also used to sell products and services, and to solicit contributions. Practically everyone in the U.S. with a phone has been called (often at an inconvenient time) and asked to purchase something. Similarly, many households could measure their direct solicitation mail, or “junk mail,” by the pound. When interviewers call homes, they are often met with refusals even before they can explain the nature of the call. A significant number of mail surveys are thrown away without ever being opened. Sales efforts disguised as surveys compound this problem.

In addition, the level of distrust in government activities has increased dramatically over the past 20 to 30 years. Many respondents are unwilling to share information with government agencies (such as MPOs and state Departments of Transportation [DOTs]) unless required to do so by law. Americans attach an extremely high value to their privacy rights, so they will often refuse to cooperate with voluntary government data collection efforts. Survey cooperation rates are higher in other countries where survey respondents are more accustomed to government inquiries.

1.7 Increasing Analytical Demands

As decision makers and the public at large are becoming more familiar with (and to some extent, more skeptical of) surveys, survey researchers are being asked to answer ever more complicated questions. Surveyors are being asked to evaluate differences between very specific market segments to help identify market niches for products and services. Such analyses require more detailed survey instruments, and greater reliance on questionnaires customized to specific respondent groups.

In addition, analysts are conducting more robust statistical analyses on the survey results to provide more usable information to decision makers. Twenty years ago, the use of complex statistical modeling procedures on survey data was limited to a few specific fields like travel demand forecasting. Today, most survey analysis efforts employ reasonably complex statistical analyses, taking advantage of advancements in the analytical capabilities of desktop computers. The increased demand for more complex analyses is requiring surveyors to increase the efficiency and quality of surveys.

1.8 Technology Advancements for Surveys

Over the past several years, most travel survey efforts have utilized computer technology advancements. Telephone interviewing is now dominated by centralized interviewing facilities and by Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) systems. In addition, the use of computer assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) techniques is becoming common in intercept surveys. These technologies increase the efficiency of survey efforts by allowing for on-line error checking during interviews and by obviating the need for most coding and keypunching tasks.

The rapid growth in the availability of GIS to transportation planners has also affected the way travel surveys are conducted and analyzed. GIS are commonly used in geocoding travel survey data once it has been collected. In addition, some recent survey efforts have relied on GISs to geocode origins and destinations in real-time during interviews. In these efforts, interviewers are able to determine whether the geographic information obtained is sufficient for analysis purposes or whether additional details need to be sought. This technique addresses one of the most difficult challenges of travel surveys, the need for reliable geocoding of locations.

1.9 Using This Manual

Nowhere is it more true than in developing travel surveys that the “devil is in the details.” This manual focuses on many detailed aspects of travel surveys, because we have learned hard lessons about the importance of seemingly mundane surveying details. This manual is intended to help individuals responsible for implementing travel surveys avoid some of the most common pitfalls.

However, this manual cannot be used as a “cookbook.” Every survey effort and region have specific qualities that must be addressed in the design and implementation of travel surveys. Analysts need to consider their specific data needs and survey constraints before embarking on a survey effort.

The approach adopted in this study was to conduct the research in two consecutive phases. In the first phase, potential areas for standardization were identified, the level of effort to research each was estimated, and a subset selected for potential work in the second phase. In the second phase, those areas selected for investigation were formulated into standardized procedures or guidelines, depending on the level of specificity thought to be appropriate. It must be stressed that it was not the intention in this study to establish standards. Rather, the goal of the study was to develop recommended standardized procedures or guidelines for consistent practice that agencies could require in the surveys conducted in their areas or that survey practitioners would voluntarily apply.

The research in this study was initiated by a literature review on personal travel surveys, as well as a review of relevant research and current practice of state Departments of Transportation (DOTs) and MPOs. Standardized procedures used or promoted by survey research organizations or associations—such as the Council of American Survey Research Organizations (CASRO), the European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research (ESOMAR), and the International Standards Organization (ISO)—were also reviewed.

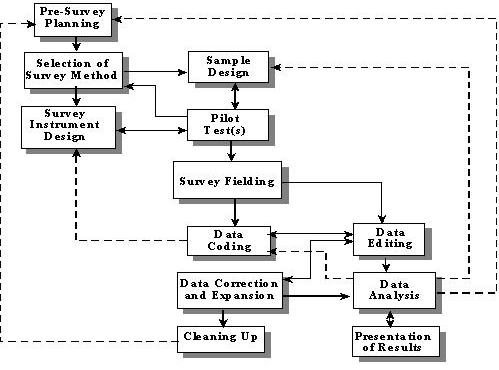

The procedures and assessment measures were identified as candidate procedures for standardization in the study using information from two sources. First, candidate procedures and measures were identified from the literature and practice review. Second, they were identified by considering the chronological steps in survey planning and execution, similar to that defined by Richardson et al. (1995) and shown in Figure 1. In reviewing each step of the process, the elements that appeared susceptible to standardization were identified based on the literature review, on team members’ experience, and on the potential for standardization to aid or stagnate the design of personal travel surveys.

Figure 1: The transportation survey process (Richardson et al., 1995)

Once identified, the candidate procedures for standardization were evaluated. The criteria used to evaluate them included extent of current use, perceived value, affordability, common definition, uniform method of application, and whether there were interdependencies between the procedure or measure and other procedures or measures. Weights were assigned to the criteria and, each candidate procedure or measure was scored on the criteria. A total score for each candidate process was established by summing the product of the weight and score on each criterion. These scores were used to prioritize the candidate procedures for review in the remainder of the project.

Some survey procedures and assessment measures required no further work before being recommended as a standardized procedure, but most required further analysis to assess their effectiveness and applicability. Some procedures and measures were tested using existing data sets, such as the 1995 Nationwide Personal Transportation Survey (NPTS), or recent metropolitan travel surveys. Two surveys were specifically conducted to address issues that could not be answered using existing data. The first survey involved testing the impact of having the same interviewer (or at least a limited number of interviewers) deal with the same household throughout the survey. The results were compared with those using regular interviewing procedures where there was no attempt to keep the same interviewer in consecutive contact with the same household. The second survey involved undertaking a non-response survey to determine the probable reasons for refusing to respond or for terminating part way through the survey process. The results were used to suggest strategies that could be used to increase response rates by changing aspects of the design and conduct of the survey.

It is expected that the information in this report will be useful to transportation practitioners in state DOTs and MPOs in preparing statistically sound data collection and management programs. It is also expected to be useful to travel survey professionals in designing their surveys, training their staff, managing the survey process, reporting the results, and archiving the data. The opportunity to compare results among travel surveys and to assess the potential of transferring data from one location and time period to another will be enhanced with the application of the recommendations in this report. At the same time, these recommendations should not prevent introduction of new procedures to thereby stifle innovation; a balance must be maintained between standardization and new development. Also, allowance should be made to amend or update the recommendations of this report as new and improved information is gained.

REFERENCES

Bonnel, P. and J. Armoogum (2005) National Travel Surveys – What Can We Learn from International Comparisons? Proceedings of the European Transport Conference, London.

Cambridge Systematics (1994) Travel Survey Manual. Travel Model Improvement Project (TMIP) report prepared for the U.S. Department of Transportation and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, D.C. Lead Author: Kevin Tierney. (Available at http://www.travelsurveymethods.org/pdfs/TravelSurveyManual.pdf and ftp://ftp.camsys.com/temp/outgoing/Travel_Demand_Survey_Manual/index.htm.).

Cervero, R. (1996) Mixed Land Uses and Commuting: Evidence from the American Housing Survey. Transportation Research A, 30 (5), 361-377.

Chalasani, S. (2005) Enriching Household Travel Survey Data: Experiences from the Microcensus 2000, paper presented at the 5th Swiss Transport Research Conference, Ascona, March 2005.

Chapleau, R. (1992) La Modélisation de la Demande de Transport Urbain avec une Approche Totalement Désagrégée. In Proceedings of the 6th Annual World Conference on Transportation Research (WCTR). Lyon. Vol. 2, pp. 937-948.

Dähne, O. and T. Reinhold (2008) Monatliche Mobilitätsprofile Vollständig Ermitteln. Internationales Verkehrswesen, 60 (3), 68-72.

Department of Transport (2005) The First South African National Household Travel Survey 2003, Technical Report, Pretoria.

Endemann, P., Maleika, A. (2005) Mobility in Frankfurt/Rhine-Main – Evidence from the German National Travel Survey (NTS), Proceedings of the European Transport Conference, London.

Endemann, P. and G. Müller (2000) Rail-Oriented Development – Potentials, Impacts, Policies. Proceedings of the European Transport Conference, Cambridge.

Follmer, R., Kunert, U. and J. Engert (2004) Wie mobil sind die Deutschen? Der Nahverkehr 22 (6), 8-17.

Highway Research Board (1944) Proceedings of the Twenty-fourth Annual Meeting of the Highway Research Board, Washington, D.C.

INFAS (2004) Sechs Regionen im Vergleich, unpublished work, commissioned by six German regional institutions, Bonn.

Nobis, C. and B. Lenz (2005) Gender Differences in Travel Patterns: Role of Employment Status and Household Structure. Research on Women's Issues in Transportation, Report of a Conference, Volume 2: Technical Papers: 114-123.

Olaru, D. and C. Curtis (2007) Travel Minimisation and the Neighbourhood, Proceedings of the European Transport Conference, London.

Richardson, A. J., Ampt, E. S. and A. H. Meyburg (1995) Survey Methods for Transportation Planning, Eucalyptus Press, University of Melbourne.

Shunk, G. A. (1994) TRANSIMS Project Description. Travel Model Improvement Program. Prepared for the

Federal HighwayAdministration by the Texas Transportation Institute, Texas A&M University, Arlington, Texas.Siedentop, S., S. Kausch, D. Guth, A. Stein, U. Wolf, M. Lanzendorf and R. Harbich (2005) Mobilität im suburbanen Raum. Neue verkehrliche und raumordnerische Implikationen des räumlichen Strukturwandels. Final Report of the Research Project 70.716 in the framework of the German National Research Programme on urban transport, funded by the German Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Affairs.

SAFETEA-LU (2005) Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users. United States Pub. L. 109-59, August 10.

Sommer, C., Bartels, S. and A.J. Beblik (2008) Mit PDA oder Fragebogen – Instrumente der Fahrgastbefragung, Der Nahverkehr 26 (7+8), 48-52.

Stopher, P., R. Alsnih, C. Wilmot, C. Stecher, J. Pratt, J. Zmud, W. Mix, M. Freedman, K. Axhausen, M. Lee-Gosselin, A. Pisarski, W. Brög. 2008. Standardized Procedures for Personal Travel Surveys. National Cooperative Highway Research Program Report 571, Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C. Available at http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_rpt_571.pdf. (Technical appendix available at http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_w93.pdf.)

TEA-21 (1998) Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century. United States Pub. L. 105-178, June 9.

TRB (2007) Metropolitan Travel Forecasting: Current Practice and Future Direction. Transportation Research Board Special Report 288. Washington, D.C.

U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) (1973), Federal Highway Administration, Urban Origin-Destination Surveys, Washington D.C. (reprinted 1975).

U.S. Department of Commerce (USDOC) (1954) Bureau of Public Roads, Manual of Procedures for Home Interview Traffic Studies – revised edition, Washington D.C

Zumkeller, D., P. Ottmann, B. Chold (2005) Car Dependency and Motorization Development in Germany, Final Report, Predit Program.