17.0 COMMERCIAL VEHICLE SURVEYS

Note: Significant components of this chapter come from Chapter 9 of the FHWA Travel Survey Manual. Material has been reviewed and updated by Frank Southworth, Rob Tardif, Zak Patterson, Chris Simek, Stephanie McVey and Matt Roorda .

Commercial vehicle surveys are used to collect profiles of goods and commodity movements, and truck and commercial vehicle characteristics, within particular areas of study. Surveys of this type have been conducted for several reasons, including for use in statewide, regional, subarea, and local travel forecasting models, in goods movement studies, in management systems (in particular, intermodal and congestion management systems), as well as in international border crossing freight movement studies.

At this point in time, commercial vehicle surveys are not typically performed to support most statewide and Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) travel model forecasting efforts. In most cases, states and MPOs estimate commercial and truck travel models outside of the formal travel modeling process. Secondary data sources are often used as post-processors to develop commercial/truck vehicle trip tables and models. However, as the analysis of commercial vehicle travel becomes more important in urban planning, the collection of commercial vehicle survey data will become quite important, as well.

Lau (1995) provides a comprehensive overview and analysis of the types, uses, methods, response rates, and comparisons of recently collected commercial vehicle data in metropolitan areas throughout the United States. It also describes the needs and requirements of commercial/truck data collected to support regional travel models as well as the MPO transportation planning and management system (pavement, bridge, etc.) process. See also Lawson and Stratham (2002).

A number of research reports discuss this topic of combining travel survey data with additional forms of non-intrusive, IT-based data collection (Skszek, 2001), (TRB, 2003), (Southworth, 2004), including the use of GPS technology for vehicle tracking (see Battelle, 1999) and growing number of active and passive and other roadside, on-board the vehicle and wide area sensors, including developments under the US Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration's CVISN program (http://cvisn.fmcsa.dot.gov/). GPS seems particularly well suited for commercial vehicles. Since the travel patterns of vehicles, rather than persons, are desired, the use of a GPS device on the vehicle is more likely to be accepted by the respondent. GPS also greatly reduces the burden on the respondent since destinations would not have to be recorded. This could be a substantial advantage for vehicles that make many stops per day. The use of RFID technology to track cargo movements by truck, rail, water and air is also now spreading across the freight movement industry (http://www.rfidjournal.com/).

17.1 Assembly of Background Information

Three types of background data are likely to be especially helpful to the survey team:

- Available commodity survey data;

- Data on the commercial vehicle population; and

- Commercial vehicle flow data.

These data are discussed below.

Available Commodity Survey Data

Typically, secondary data sources are used to model and forecast commercial vehicle travel patterns in lieu of collecting new survey data. Although there are a number of sources of data required to support commercial vehicle surveying efforts, there is little information collected by others which can be used directly in the development of truck/commercial travel models. Ideally, available recent survey data should provide information on commercial vehicle trips by origin and destination, vehicle type, commodity type, and time-of-day.

Following a sixteen year hiatus in federal freight activity data collection the 1993, 1997 and 2002 U.S. Commodity Flow Surveys (CFS) filled a large gap in this U.S. freight data universe. Since 2005 this gap has been further reduced by a merging of CFS data with many other federally supported freight and trade (inports and exports) data sources, and combined using a variety of data integration and synthesis methods to produce a more comprehensive picture of US freight activity for the years 1998 and 2002. Termed the Freight Analysis Framework, or FAF, this FHWA supported data and analysis program provides access to commodity flow matrices broken down by major commodity and modal classes.

Limited in its level of spatial resolution has limitations the following limitations to 131 domestic and international traffic analysis zoned, the FAF can be used to provide control totals, notably of external flows into and out of major metropolitan areas, border crossing gateways and rest-of-state regions. Built around the CFS it also provides useful value to weight (i.e. dollar per ton) and broad regional commodity by mode trip length statistics. It cannot substitute, however, more detailed spatial and commodity class specific truck or other modal flow data: and the microdata records collected as part of the nation's Commodity Flow Surveys have remained unavailable for general use due to strict controls over the release of potentially proprietary data collected as part of the US Economic Census. A detailed examination of the content and limitations of CFS data can be found in the 2005 TRB Conference Proceedings devoted exclusively to this topic (TRB, 2006).

At the local level, systematic surveys of truck travel are generally unavailable. The closest to the type of information desired by urban planners and travel modelers are usually the trip logs maintained by many commercial vehicle operators such as delivery services (United Parcel Service and Federal Express), the United States Postal Service, and many on-site repair establishments. Although these trip logs can be used to create limited commercial vehicle trip tables, they are the property of the privately held businesses/establishments, and are therefore difficult to obtain.

Potentially, an aspect of a survey team’s commercial vehicle surveying effort could be to request the voluntary provision of these commercial vehicle trip logs for a sample of local establishments. In addition, survey teams could also obtain applicable information from the CFS in order to supplement the primary data collection efforts envisioned for the survey effort.

Data on the Commercial Vehicle Population

Two data sources have typically been used to provide transportation planners and modelers with commercial vehicle population information which can be sampled to obtain commercial vehicle travel data:

- Vehicle registration lists; and

- Commercial establishment lists.

Vehicle registration lists by vehicle type and owner address are generally available to local planners and travel modelers from Departments of Motor Vehicles (DMVs). The vehicle type classifications from these lists may or may not meet the planners’ needs, depending on whether or not vehicle weight and type codes are maintained in the files, and on whether or not licenses are differentiated by vehicle type. There may also be problems in identifying passenger vehicles, pickup trucks, and small delivery vans used commercially. This source typically fails to match the population of vehicles actually operating in the study area because commercial vehicle ownership, garaging, and usage often involves two or more locations, some of which may be outside of the study area and therefore impossible to survey.

A second type of data source is an establishment listing. Commercial establishment lists are available in many forms, ranging from telephone listings to publicly maintained lists. Typically, State Departments which administer unemployment and work compensation insurance programs and proprietary databases created for sale by private firms, such as Dun and Bradstreet, maintain these listings.

No source will provide perfect data for the survey sampling frame. Potential problems involved with data obtained from these lists include:

- The lack of coverage of branch office operations in employment-based lists;

- Lists can become out of date relatively quickly;

- The lack of not-for-profit and governmental organizations in the listings; and

- The lack of employers with small numbers of workers.

An additional difficulty in using lists of this type is that they typically include many establishments which do not operate commercial vehicles. This leads to low survey eligibility rates, which, in turn, lead to increased data collection costs and longer than estimated field periods. It is for this reason that it can be useful to stratify businesses/employers by SIC/NAICS code to target industries most likely to operate commercial vehicles (See Section 17.4 below).

Commercial Vehicle Flow Data

Information on commercial vehicle flows is often valuable for model validation. This information can also be used to monitor commercial traffic into and out of major facilities such as large warehouses, piggyback rail yards, and ports. When state-of-the-art technology is available, classification counts based on the number of axles and length per vehicle can be obtained automatically at traffic count stations. More typically, planners and modelers must rely on available short-term manual classification counts, frequently collected as part of traffic operation and impact studies. Fischer and Han (2001) review the use of these and other data sources for creating a set of truck trip generation rates for use in planning models.

17.2 Commercial Vehicle Survey Design

The most basic design decision for the commercial vehicle survey team is the selection of the appropriate survey population and unit of analysis. Commercial vehicle surveys can be performed by sampling:

- Commercial vehicle trips at certain geographic locations;

- The commercial vehicles themselves; or

- The establishments that commercial vehicles serve.

If the vehicle trip is chosen as the unit of analysis, the commercial vehicle survey is a simple extension to the vehicle intercept survey described in Chapter 7.0.

When the intercept method is insufficient for the anticipated analyses, a general population survey is needed. Often, the population chosen for analysis is the commercial vehicles registered in the study area. In this type of survey, the survey team contacts the owners of a sample of the vehicles, and requests them to provide detailed travel information for the vehicle. Some larger truck fleets have been equipped with GPS tracking devices that allow fleet managers to locate trucks at any given moment. These systems can be used effectively for gathering truck-specific travel patterns continuously, with dwell times and other infrastructure specific operations information between origin-destination pairs with measures of speed and congestion systems performance, fuel consumption and hard brake events (Tardif R., 2007) with little effort by respondents. Until all trucks are equipped with GPS tracking devices and all of their information shared for transportation planning purposes, the uses of this unique data are likely to be limited to micro and macro operations analysis. While the activities of large samples of carriers equipped with GPS tracking produce traffic flows and select link matrices that support mapping analysis, expansion of these samples requires detailed link level hourly truck classification counts to expand to the truck population.

A major advantage of this approach is that registered vehicle data can usually be obtained from local DMVs at little cost. The major disadvantage is that vehicle registration lists do not typically match the commercial vehicle population in an urban areas since many trucks not registered in the areas will be garaged and operated within the area, and conversely many commercial vehicles registered in the area will typically operate elsewhere.

Because of the problem with using the registered vehicle as the unit of analysis, many commercial vehicle surveys concentrate instead on establishments (see Chapter 10). The advantage of using employers as the population to be sampled is that nearly all commercial vehicle activity in a region is associated with employment, either of the shipment originator, receiver, vehicle operator, or a combination of the three. Exceptions to this rule of thumb include rare cases of deliveries to households from external study area locations by operators also based outside of the study area. The disadvantages of using employers include the following:

- Many businesses have very limited connections with commercial vehicle trips;

- Establishing a comprehensive population of employers is often difficult;

- The costs of contacting the number of employers necessary to obtain a specified vehicle sample size may be significant; and

- Two-stage, or stratified sampling is required to account for the varying number of commercial vehicles associated with employers of different sizes and types.

The choice of the unit of analysis is likely to depend mainly on the anticipated modeling needs, but also on the schedule and resources available to implement the commercial vehicle survey. A survey based on vehicle registrations can usually be conducted less expensively. However, the primary benefit of a survey based on employers will be that it more accurately represents the entire commercial vehicle population in the particular study area.

General Fieldwork Approach

The fundamental design problem typically faced by surveyors is how to obtain travel behavior information directly from the truck/vehicle operators. In most cases, owners of private trucking and commercial businesses are not willing participants in this type of survey effort, especially if they are asked to provide operational information about their particular business. Past commercial vehicle surveys have shown that response rates may be increased by obtaining the support of the local or state motor trucking association. These organizations act as intermediaries between their constituent organization and the government entity often sponsoring or funding the survey effort and can be invaluable in promoting the survey. (Hunt, Stefan and Brownlee, 2006) In Canada, federal and provincial transport agencies conduct national carrier roadside surveys as part of the Transport Canada - National Roadside Survey (NRS) every 5 to 6 years in conjunction with enforcement staff with 95% response rates. Traditionally, carrier associations have supported these data collection efforts since these agencies have proven the link between improved truck activity knowledge and direct freight supportive infrastructure investments based on the time-series data.

In addition, the survey design must include a convenient mechanism to obtain travel information directly from the vehicle operator, which is not always evident. Therefore, creative methods for obtaining important travel behavior from the appropriate businesses must be built into the survey design process. Standard design features for the commercial survey include the following steps:

- Contact businesses to obtain approval for survey participation;

- Identify survey method;

- Develop data recording method; and

- Develop survey expansion method.

Recent experience in Chicago, Phoenix, Alameda County (California), and Houston has shown that the following multi-step approach is necessary to conduct and administer a successful commercial vehicle survey:

- Contact Businesses – Initial contacts with business owners or employers should be established by telephone. Supplemental contacts should be made by mail and/or in person (particularly for operators of large fleets) to recruit survey participants. Typically, the survey mail-out instrument requests establishment, vehicle, and travel behavior data (trip diary forms) for a single-travel day. Data retrieval is usually conducted either by mailback or telephone contact.

Attempts to simplify this process to a mailout/mailback strategy have been made in at least one recent truck survey (in Phoenix) which was based on vehicle registration data. However, because the response rates were so low in the pretest, the approach was revised to represent the approach described above. Incentives (e.g. chance to win a prize for participation) can help to increase response rates.

Details and potential refinements of this general fieldwork strategy are discussed in subsequent sections of this chapter. An important issue to address during the survey design is the degree of coordination between the commercial vehicle survey, workplace surveys, and vehicle intercept surveys discussed in Chapters 10.0 and 7.0 respectively. For example, if an employer database is used as the sampling frame, then the procedures used to design the workplace and establishment survey should be combined with those documented below. This will minimize the effort required for meeting data needs and reduce the number of business/employer contacts that have to be made. Similarly, specific truck movements may be well captured by vehicle intercept surveys, reducing the data needs for the commercial vehicle survey.

- Data Recording Methods – Typically, the recruitment of businesses/employers to survey is conducted by obtaining vehicle registrations or by contacting businesses directly by telephone. Data retrieval and recording methods for each include the following approaches:

- Vehicle registration information is obtained through the Department of Motor Vehicles. Recruitment of businesses for survey participation are typically obtained through telephone contacts and the use of CATI.

- Retrieval of survey forms is handled by either providing envelopes with return of address and postage or mailback postcard forms. Returned surveys, using either method, are directly input into established computer databases or by using telephone/CATI. CATI is used to directly enter survey responses for several survey types discussed in this manual.

- Employer contacts and subsequent survey recruitment are typically made by telephone and CATI. In some cases, personal contact is made by sending out initial survey participation forms designed to obtain business participation in the survey. Data entry and retrieval use similar methods described above for the vehicle registration approach.

- Survey Expansion Method –For the vehicle registration approach, the sample expansion method includes:

- Developing a vehicle factor based on the number of vehicle registrations divided by the number of responses by weight classification or truck type; and

- Developing a trip factor based on the total number of trips per truck obtained from the trip diary forms (typically, each vehicle operator is asked for detailed travel behavior information for a limited number of trips, e.g., for a given period, day, or week).

The sample expansion method typically used for the employer contact approach includes:

- Developing an establishment factor based on the number of employers divided by the number of establishments participating in the survey;

- Developing a matrix based on employer size, business type (SIC code), and/or geography (location) in order to define the establishment factor identified above;

- Developing a vehicle factor based on the number of vehicles used by a given establishment divided by the number of employers surveyed (this factor can be truck type-specific); and

- Developing a trip factor using similar methods described above for the vehicle registration approach.

17.3 Organizing the Commercial Vehicle Survey

As specified above, the design of the commercial vehicle survey typically considers the vehicle registration or employer contact approach. If the employer contact approach is used, close coordination with the development and implementation of the workplace and establishment survey is desirable. Similar to the other survey types identified in this manual, and once the businesses for surveying have been identified, the following design issues must be determined:

- What is the appropriate survey approach?

- Should the surveys be conducted using telephone interviews or be self-administered?

- What count data are needed for the survey and how can it be obtained?

- Should incentives for participating in the survey be offered?

The fieldwork approach must be identified in the beginning stages of the survey effort. General descriptions of the two typically used approaches, vehicle registrations and employer contacts, are discussed in Section 17.2.

Once this approach is identified, the survey design must be determined. This design should consider either the initial telephone contact, mail-out and follow-up telephone contact/CATI approach or the mail-out, self-administered questionnaire, and mail-back approach to obtain the travel behavior information required for analysis and travel modeling. Both designs have been used for surveys of this type, with the higher response rates associated with the telephone interviews. Similar to other survey types, telephone interviews are typically conducted by specialized market research firms. The procedures required for implementation of telephone surveys are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 6.0.

The problematic issue associated with conducting telephone interviews for this type of survey is to identify the appropriate mechanism to directly contact the commercial vehicle operators. As stated previously, this direct operator contact is essential to ensure that the proper level of trip-making and travel behavior data is obtained. Other potential contact persons at employers and businesses include dispatchers and business owners that may be able to answer specific travel logistics questions about their commercial vehicle fleet. Online alternatives to conducting surveys are also becoming more commonly used.

With the self-administered surveys, similar and additional problematic issues must be addressed in order to meet the needs of the survey. For example, a mechanism has to be identified to distribute the survey material from the employer/owner to the appropriate vehicle operators. This must be defined early on in the survey design once the self-administered survey is selected. Typically, the distribution of questionnaire forms is administered by the business employers’ owner or fleet dispatcher. Additional issues include ways in which completed survey forms are collected and specific vehicles are identified as survey participants. The self-administered questionnaires are sent directly to the surveyor either by the individual vehicle operators surveyed or by the employer/owner who collects the completed surveys from the individual vehicle operators. Similar to the workplace and establishment surveys, better response rates occur when the employer/owner is responsible for collecting completed questionnaires from operators for mail-back. Recent commercial vehicle surveys have shown that some level of personal assistance (in the form of an establishment site visit before the assigned travel day) by a survey firm representative to address any questions or concerns the recruited establishment may have may help increase survey response rates (Hunt, Stefan and Brownlee, 2006).

The following primary and secondary traffic data can be obtained to supplement the information obtained from the commercial vehicle survey:

- Truck classification counts by weight and activity at cordon and/or screenline locations;

- Truck classification counts at area Truck Centers and Weigh Stations;

- U.S. Census Commodity Flow Survey;

- Vehicle Trip Logs from surveyed businesses; and

- Truck classification counts at permanent station locations on state routes and major highways.

Much of this information can be obtained by using the traditional data collection methods designed for other types of surveys and travel models. For example, the traffic data collected for vehicle intercept surveys can also be used to identify commercial vehicle trucks movements at specific count locations. These data can be used to expand the results of the survey to estimate commercial vehicle volumes currently operating on the roadway network. The cordon and/or screenline commercial vehicle data are typically collected at the same locations established for highway network automobile and transit traffic. This ensures consistency with other models developed within the regional travel modeling system such as the development of automobile trip tables by trip purpose using the traditional Four-Step modeling approach.

17.4 Sampling

Sampling strategies are typically conducted in two stages. The first stage involves the selection of the business/employer sample from all the businesses within the study area. The second is the selection of the commercial vehicles (classifications) to be sampled within the businesses selected for surveying. The sampling techniques used for the commercial vehicle surveys can be dependent on other survey efforts taking place, especially the workplace and establishment survey, which use similar methods to define the sample of businesses/employers.

Vehicle registration approach. In order to obtain a reasonable level of information on trips by heavy/large commercial vehicle classifications, sampling should be stratified by vehicle type. Typically, three to four categories are selected for sampling based on weight or the number of axles for each vehicle. Sampling rates are usually established to achieve an equal number of responses by each vehicle type. Or sampling can be weighted based on reported aggregate registrations by vehicle type.

Within each category, vehicles selected for contact should be ordered randomly, by registration number, for example, to avoid geographical and other biases if all vehicles are not contacted.

Employer contact approach. The techniques used to sample workplace and establishment surveys and the issues associated with identifying the sample of employers are discussed in detail in Chapter 10.0. If the commercial vehicle survey is being conducted independently of the workplace and establishment surveys, then it may be desirable to stratify businesses/employers by NAICS code and target the sample on industries most likely to operate trucks and other commercial vehicles. Otherwise, many contacts will be non-productive and inappropriate for surveying because of limited commercial activity. Sampling of vehicles within the businesses will be warranted for establishments with large commercial fleets. This will more than likely be the case for light and medium vehicles because heavy vehicle operators may be difficult to locate and subsequently survey.

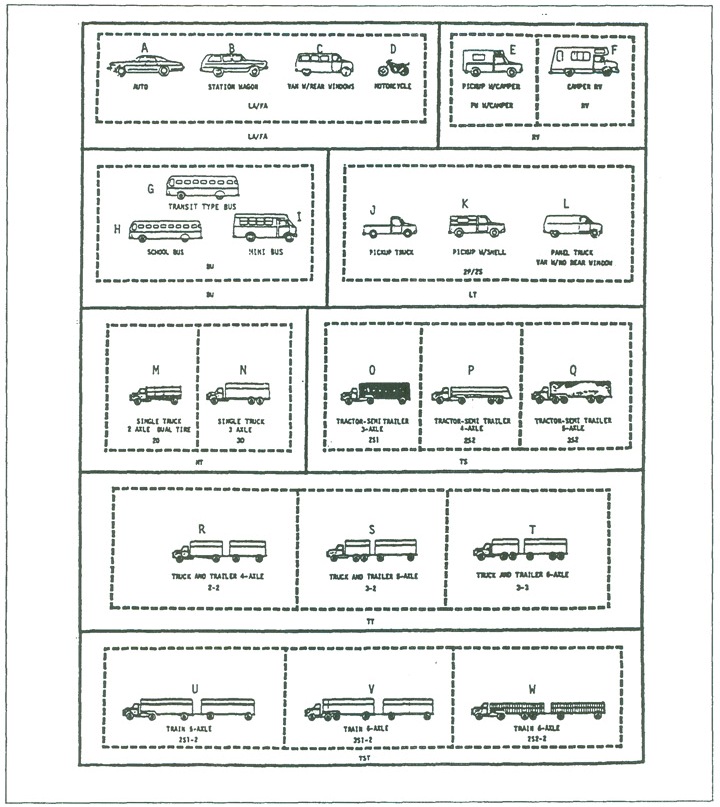

17.5 Drafting and Constructing the Commercial Vehicle Survey Data Elements

Typically, planners design commercial vehicle surveys to determine vehicle owner information such as industry type, number of commercial vehicles, and number of employees; vehicle information such as size, weight, and body type; and information on vehicle usage for a typical travel day. For each commercial trip made on the specified travel day, information to be obtained is typically desired for origin and destination locations, trip start and end times, odometer readings, land use and/or industry type uses at the identified origin and destination locations, activity at the stop locations (loading, unloading, meal stop, etc.), stop location (on- or off-street), and vehicle contents (commodities) during the trip.

The level of detail concerning vehicle contents can vary from simply noting whether the vehicle is empty or loaded, to a detailed commodity description and/or code. Information on the commodities transported is not a necessary element for most urban planning and travel modeling applications, but may be desired for particular urban, regional or interregional goods movement studies.

Survey Instruments

Similar to other surveys described in this manual, the survey instrument should be constructed to elicit the responses to the most pressing problems of interest. Where possible such responses should be suitable for use in the travel demand modeling process. This includes drafting the appropriate questions and constructing the survey instrument to meet travel modeling needs. The telephone and self-administered survey approaches are typically constructed differently and require different questionnaire designs.

The telephone interview questionnaires are typically more detailed and focus on obtaining other information besides travel behavior. For example, surveyors may obtain commodity flow and other non-related travel behavioral data. Telephone interview questionnaires are also designed to allow for quick interviewer tallying of responses by using personal interview scripts and CATI programs.

The self-administered surveys typically contain fewer questions and are targeted for quick response time. The survey questionnaires must also be clear and easy for respondents to fill out. Generally, a series of instructions are provided directly on the questionnaire form to assist vehicle operators with instructions on how to respond to the questionnaire. Return address and postage are required for a self-administered survey that has a questionnaire mail-back option.

In addition, it is recommended that the survey team ask commercial vehicle operators to review, test and comment on early drafts of the survey questionnaire and materials. This step will ensure that common terminology is used and understood.

Survey questions that might appear on a commercial vehicle survey include:

- Business/employer location and address;

- If appropriate, the Truck Center/Weigh Station location where the survey was completed;

- Ultimate trip origin and destination including state, city, and nearest intersection;

- Interim trip origins and destinations specifying segments/previous stop locations of the entire trip (related to long-haul operators);

- Start and end times of the entire trip (including all trip segments);

- Major routes used for travel on the highway network;

- Frequency of trips using this particular route by day, week, and month;

- Frequency of trips using alternative routes by day, week, and month (including reason for using alternatives such as congestion, time-of-day, etc.);

- Truck classification type and size categories (heavy, medium, light, small commercial);

- Commodity/good that is being transported as well as characteristics of the goods (value, etc., including whether or not the load is empty); and

- If appropriate, locations for pickup and delivery of goods.

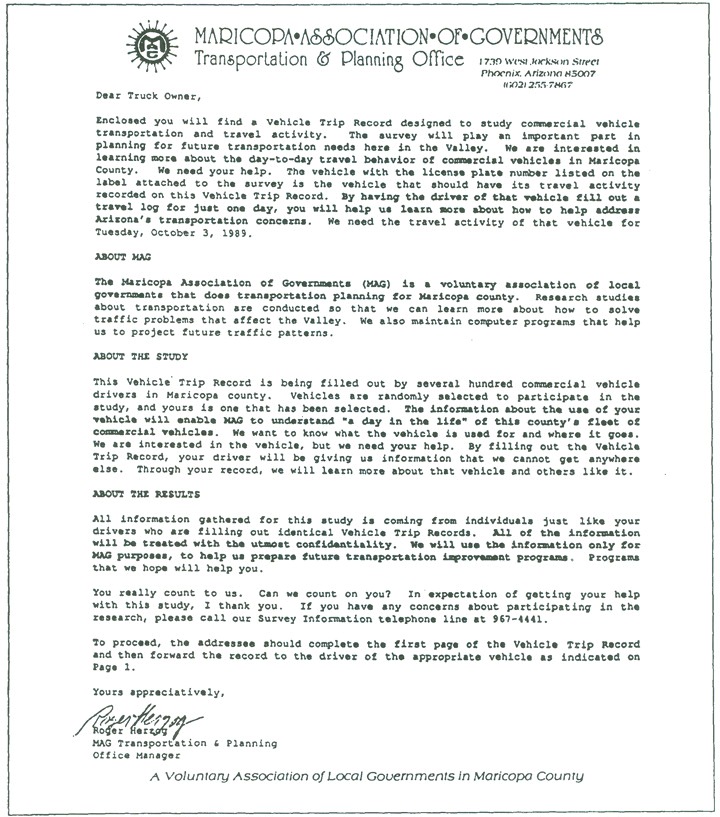

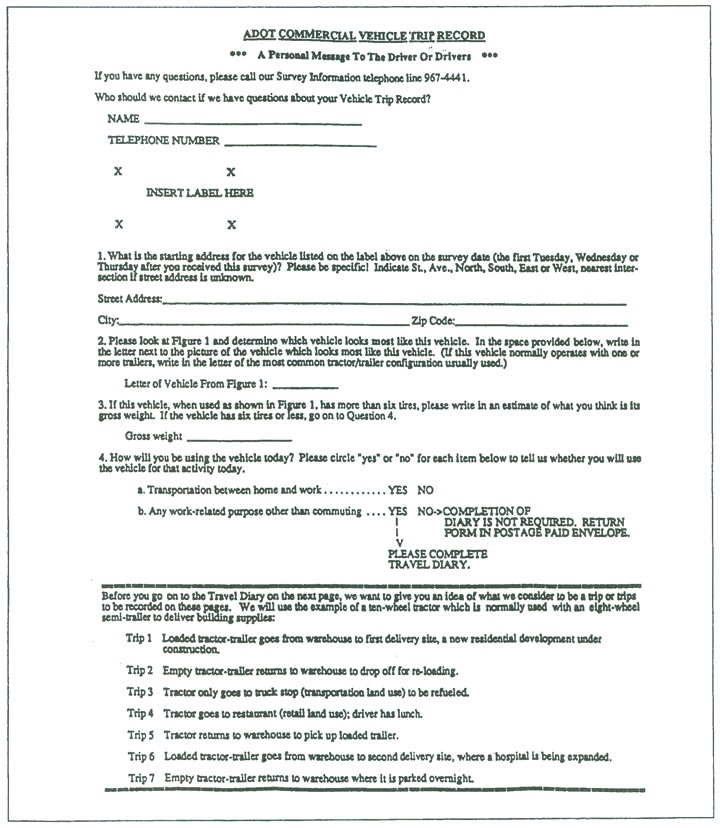

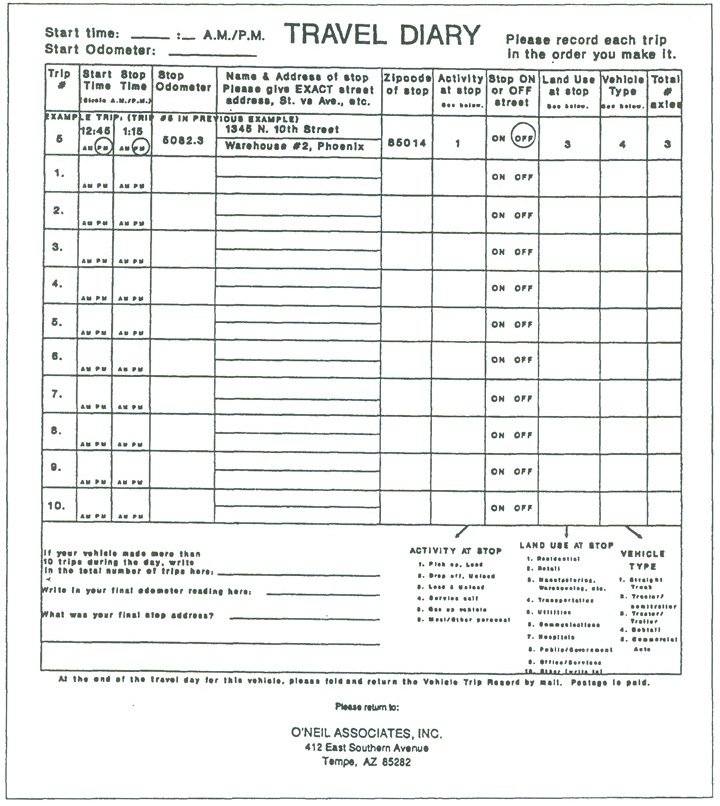

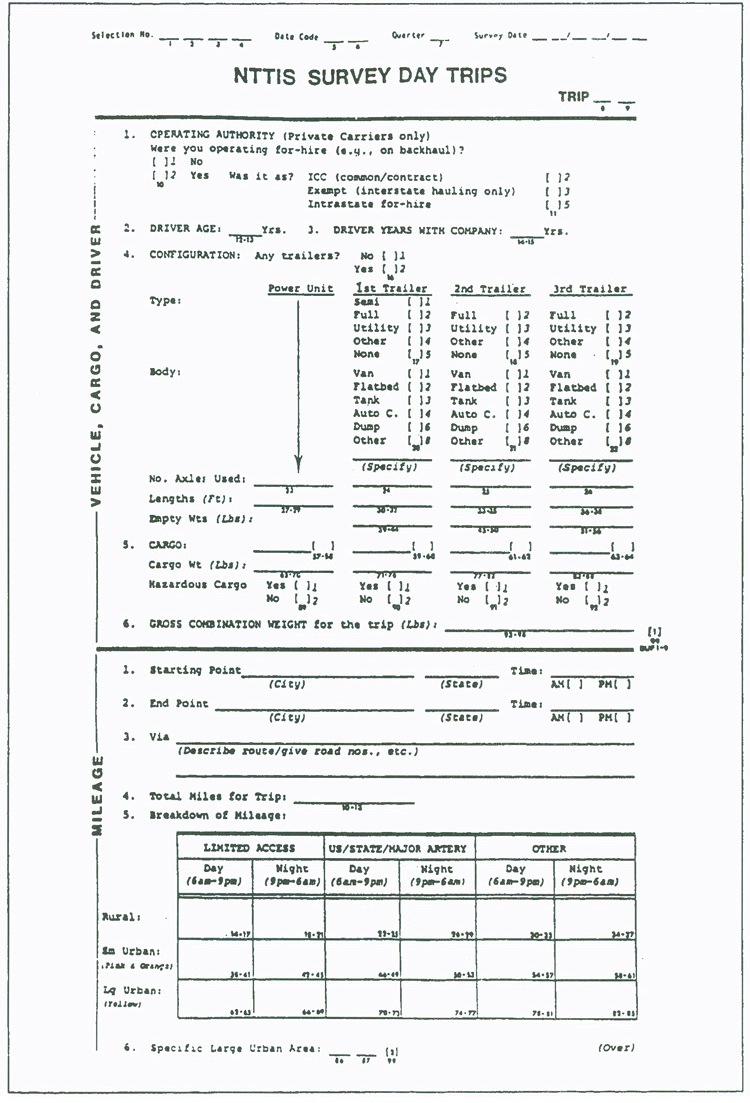

Greater success (i.e. higher response rates) may be obtained by including questions that interviewees are likely to want to respond to such as their opinions about how much, and where, they experience traffic delays, or regulations that make their job more difficult. The survey instruments from several recent commercial vehicle survey efforts are shown in Figures 17.1 through 17.4. The Canadian National Roadside Survey offers an excellent example of such a survey instrument (see Earth Tech Canada Inc., 2008, for a description of the practical issues involved in conducting such a survey).

17.6 Pretesting

As with any survey, pretesting should be carried out prior to the full implementation and administration of the survey. In the case of the self-administered survey, surveyors can rely on surveys already carried out in other locations to reduce the need for extensive pretesting. For telephone interview surveys, it is important that the surveyor test the entire process to ensure each component of the survey is feasible and obtains the appropriate level of information required for analysis and travel modeling purposes.

In some cases, self-administered (mail-back) survey pretesting can be administered on a small scale to persons within your company/agency to identify inconsistencies and other issues associated with the format and wording of the questionnaire. In previous chapters of this manual, procedures and requirements for pretesting are discussed in greater detail.

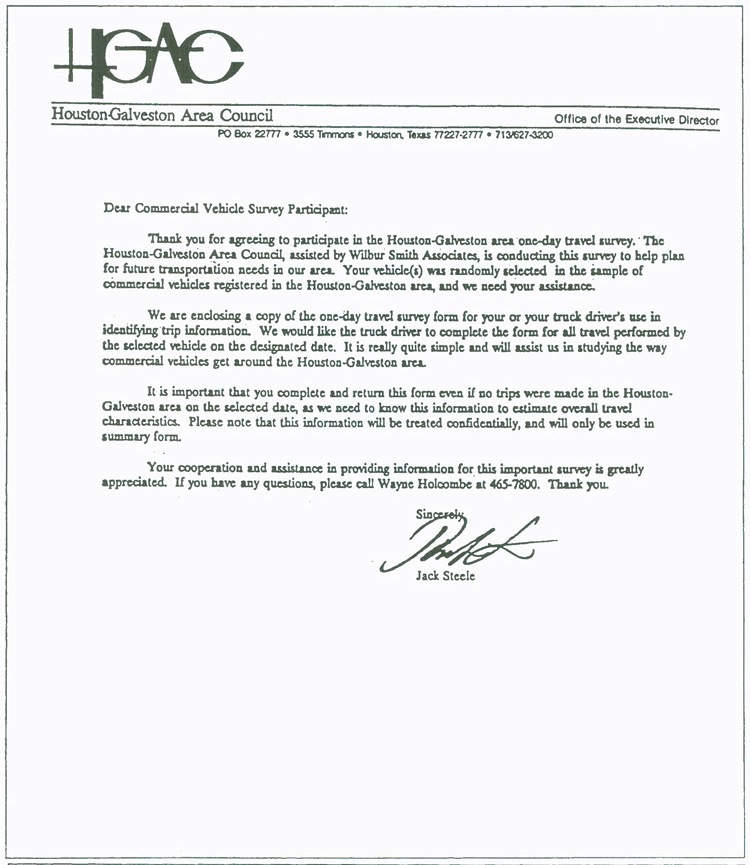

Figure 17.1 Sample Commercial Vehicle Survey Travel Diary Package from Phoenix

Figure 17.1 Sample Commercial Vehicle Survey Travel Diary Package from Phoenix (continued)

Figure 17.1 Sample Commercial Vehicle Survey Travel Diary Package from Phoenix (continued)

Figure 17.1 Sample Commercial Vehicle Survey Travel Diary Package from Phoenix (continued)

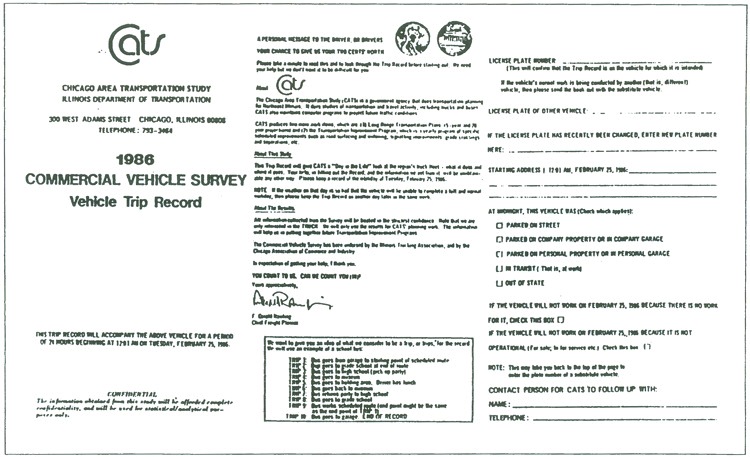

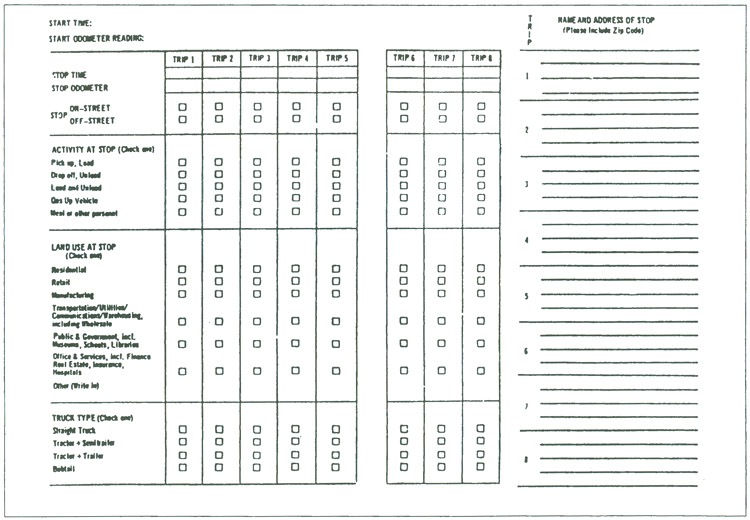

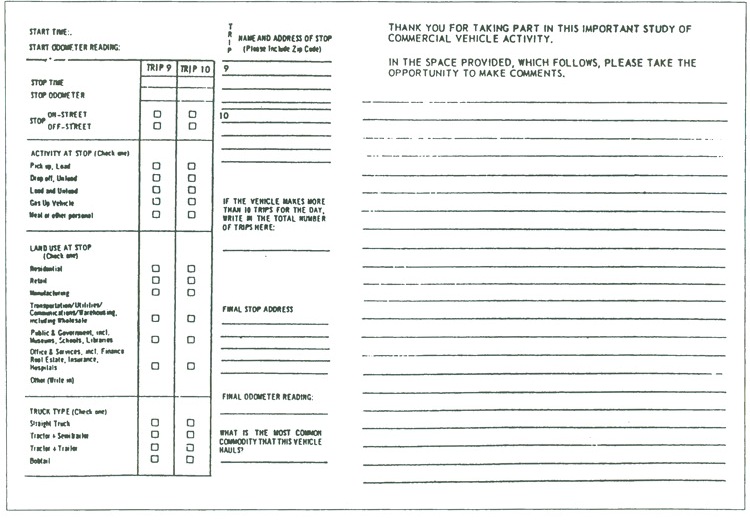

Figure 17.2 Sample Commercial Vehicle Survey Trip Record Forms from Chicago

Figure 17.2 Sample Commercial Vehicle Survey Trip Record Forms from Chicago (continued)

Figure 17.2 Sample Commercial Vehicle Survey Trip Record Forms from Chicago (continued)

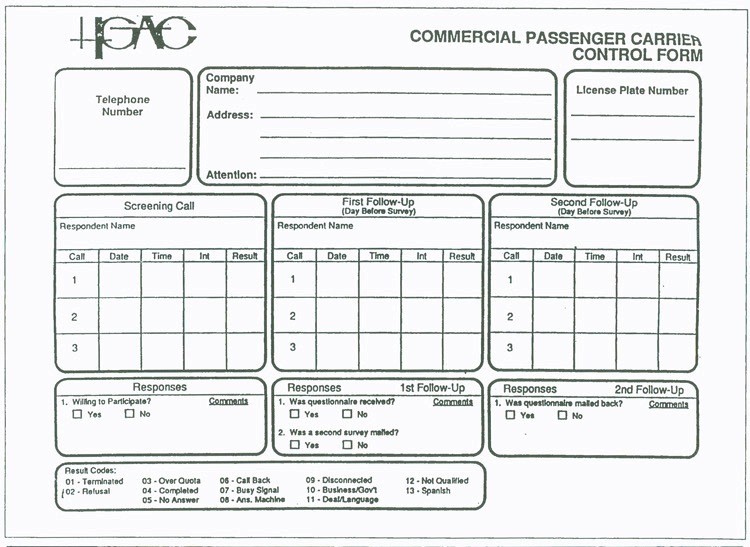

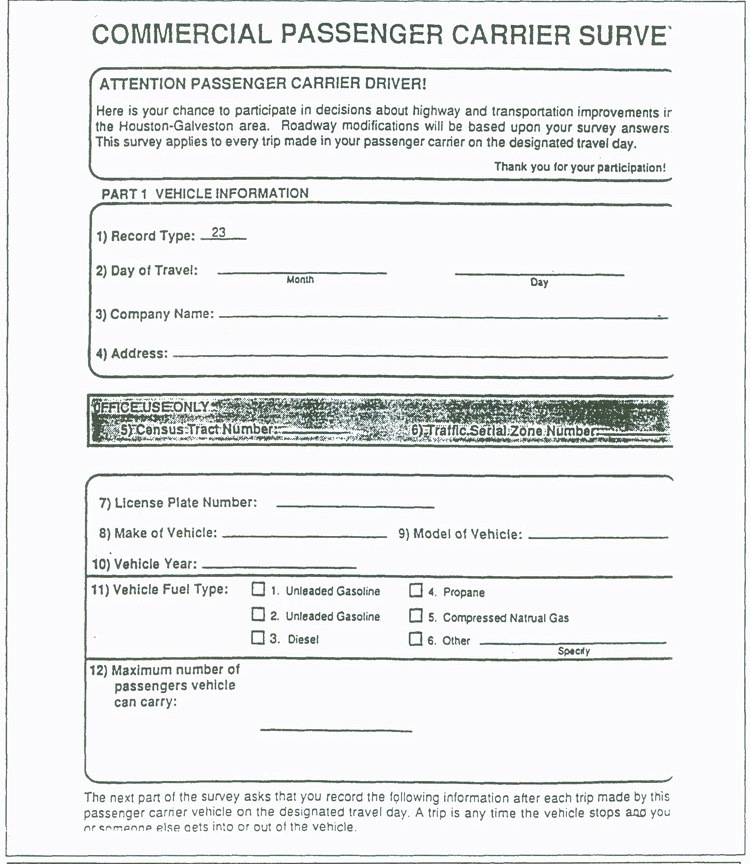

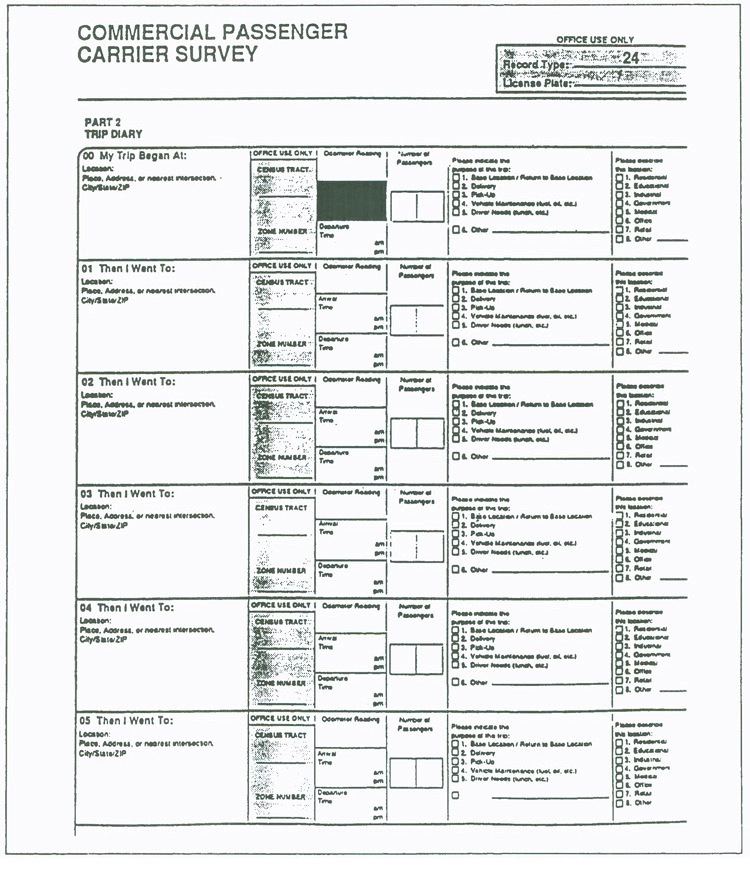

Figure 17.3 Sample Commercial Vehicle Survey Forms from Houston-Galveston

Figure 17.3 Sample Commercial Vehicle Survey Forms from Houston-Galveston (continued)

Figure 17.3 Sample Commercial Vehicle Survey Forms from Houston-Galveston (continued)

Figure 17.3 Sample Commercial Vehicle Survey Forms from Houston-Galveston (continued)

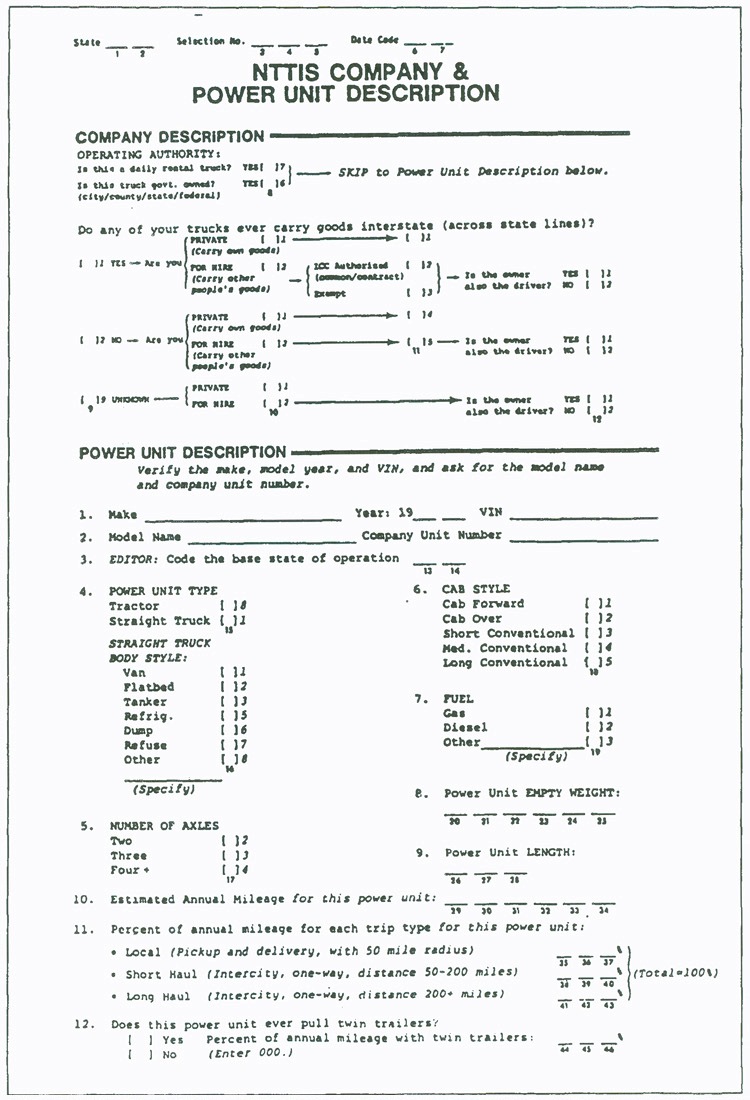

Figure 17.4 National Truck Trip Information Survey Power Unit Description and Survey of Day Trips

Figure 17.4 National Truck Trip Information Survey Power Unit Description and Survey of Day Trips (continued)

17.7 Training and Interviewing

Similar methods for survey training described in other chapters of this manual can be used to train and brief the surveyor (telephone interviewer) staff designated to conduct the commercial vehicle survey in the field. For example, the training methods described for the household travel survey can be used for the telephone interview approach described in this chapter. In addition, the training methods for the Roadside Handout Survey described in Chapter 7.0 and the workplace and establishment surveys in Chapter 10.0 are very similar to the self-administered (mail-back) survey described in this chapter.

Interviewer and surveyor courtesy and persuasiveness in getting cooperation from employers and owners is essential to the successful completion of the commercial vehicle survey. Identifying the ‘path’ from the initial business/employer contact to the appropriate decision maker who will agree to participate and permit the survey to continue is also essential. This ‘path’ also provides the reliable link between the employer and vehicle operator.

In most cases, survey training is conducted prior to the pretest and the implementation of the overall survey with all participating surveyors and interviewers. The training session is typically conducted several days before the scheduled pretest and overall survey dates. Surveyors are briefed on the purpose and procedures on how to conduct the survey. Items generally covered by survey administrators include:

- Project briefing describing the background and purpose of the survey and a description of survey assignments for all surveyors;

- Demonstrations of the procedures of the survey administration describing surveyor/interviewer responsibilities for distributing questionnaires, survey schedules, etc.; and

- Survey procedures checklist provided to the surveyors and/or interviewers during the initial briefing session, including authorization letters and background material.

In commercial vehicle surveys designed for administration at Truck Center and Weigh Station locations, it is important for the survey administrator to coordinate with the surveyors to ensure that they have been distributed all of the necessary survey materials required to successfully carry out the survey. These survey materials may include:

- Survey forms;

- Record keeping forms;

- Writing instruments;

- Handheld devices for data collection; and

- An authorization letter describing the intent of the survey and the request for survey participation.

The survey administrators must also provide additional instructions to the surveyors about the distribution of forms to dispatchers and employers, as appropriate. If the survey questionnaires have serial numbers, surveyors will be able to track the Truck Center/Weigh Station, and employer locations and times of survey distribution.

Variations of interviewing procedures can be used depending on the survey method selected and the sample of commercial vehicles to be surveyed. Also, survey notices should be distributed among businesses/ employers and Truck Centers/Weigh Stations according to the survey method chosen.

17.8 Coding

Commercial vehicle survey coding is conducted using similar procedures used for other surveys described in this manual. Similar techniques are used to code both the self-administered (mail-back) and telephone interview surveys. The survey questionnaires are typically designed to be self-coding (except for the origin-destination information), where each survey response can be coded to correspond to its answer check box number. Data coding can either be completed manually by the surveyors conducting the telephone interviews, by CATI, or by vehicle operators completing the self-administered survey.

Typically, as with other surveys, data are punched into a numerical ASCII data block for a specified width and length as determined by the number of questions/responses and sample size of the survey. Individual survey questionnaire responses are typically given an identification number to track the responses for each business/employer and vehicle operator surveyed. Survey origins and destinations must be geocoded to identify the geographic locations of the commercial vehicle trips surveyed. Chapter 14.0 provides a detailed discussion of survey geocoding techniques.

17.9 Cleaning and Editing

Similar data cleaning and editing techniques used for other surveys described in this manual are also conducted for the commercial vehicle survey. As stated in previous chapters, completed questionnaires should be edited as soon after collection as possible to ensure that the proper surveyor techniques have been used and the appropriate information has been obtained. Range checks should be conducted to identify any data inconsistencies that may occur in the coding process and to verify the accuracy of the data. Clearly invalid responses should be checked for and removed before data are analyzed. If data are collected over the web, this work can be done in real-time and survey appropriateness can be examined (and possibly changed) as soon as data starts to come in.

REFERENCES

Brownlee, A.T., J.D. Hunt and K.J. Stefan (2006). Establishment-Based Survey of Urban Commercial Vehicle Movements in Alberta, Canada. Journal of the Transportation Research Board, No. 1957, pp. 75-83. Transportation Research Board , Washington, DC.

Earth Tech Canada Inc. (2008). 2006-2007 Commercial Vehicles Survey Field Operations Report. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Transportation.

FHWA (2008). Freight Analysis Framework (FAF). Office of Freight Management and Operations, Federal Highway Administration. Washington, D.C. Accessed online 10/3/2008 (http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/freight/freight_analysis/faf/index.htm).

Fischer, M.J. and M. Han (2001). Truck trip generation Data. NCHRP Synthesis 298, Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C.

Lawson, C.T. and J.G. Strathman (2002). Survey Methods For Assessing Freight Industry Options. Federal Highway Administration Report FHWA-OR-RD-02-14. Washington, D.C.

Skszek, S.L. (2001). “State-of-the-Art" Report on Non-Traditional Traffic Counting Methods. Report prepared for the Federal Highway Administration and Arizona Department of Transportation. FHWA-AZ-01-503. Washington, D.C.

Southworth, F. (2004). A Preliminary Roadmap for the American Freight Data Program.

Report to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, United States Department of Transportation Washington, D.C.

Tardif, R. (2007). North American Freight Transportation Data Workshop - Using Operational Truck Location Data to Improve Understanding of Freight Flows. Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C.

TRB (2003). A Concept for a National Freight Data Program. Special Report 276. Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C. (http://gulliver.trb.org/news/blurb_detail.asp?id=1730).

TRB (2006). Commodity Flow Survey Conference. Transportation Research Circular E-2088: 29-46. http://www.trb.org/publications/circulars/ec088.pdf.

TRB (2011). NCHRP Synthesis 410: Freight Transportation Surveys. Transportation Research Board, Washington, D.C.