| | | |

Uploading .... Uploading ....CHAPTER 22.0 LONGITUDINAL SURVEYSNote: Significant components of this chapter come from Chapter13 of the FHWA Travel Survey Manual. Material has been reviewed and updated by Tomas Ruiz Sanchez, with assistance from Guang Xiang Chen and Neil Kilgren. 22.1 IntroductionLongitudinal surveys are methods for collecting dynamic information from subjects. In Transportation studies, we are interested in how travel behavior of people changes over time. Three basic survey strategies can be identified in the Transportation area. The traditional single cross-section (SCS) of data consists of collecting information from a representative sample of a given population. The objective is to characterize that population in one point of time or snapshot. It is possible to use several SCS surveys carried out in the same area, each designed for measuring one specific period, to get estimates of change. On the other hand, in repeated cross-sections (RCS) a new sample is drawn periodically (survey waves) from the same closed population. Consecutive samples do not overlap at all. Recently, this type of survey is also known as continuous survey (Stopher, 2008). Finally, panel surveys (P) are characterized by using the same set of respondents over time. Consecutive samples completely overlap. Longitudinal surveys are required to account for important influences such as the timing of change, the role of habit and expectations, and the degree of stability and/or growth of key exogenous forces (Hensher, 1986).22.1.1 Advantages and Drawbacks22.2.1.1 AdvantagesTime series formed by registers or records are continuous and cheap source of data (Kish, 1987).Longitudinal data contain age and period (secular trend) effects, and RCS data also contain cohort effects (Hensher, 1986). However unlike an SCS is unable to account for these temporal effects, a longitudinal study can identify the important role of the timing of events which may be a cause or consequence of processes being explained.In contrast to multi-wave panel data, RCS data at two or more points in time measure only net changes over the course of the intervening time periods. A panel study enables identification and study of the “changers”.Only longitudinal data can assess the influence of the timing of events in the behavior process (Hensher, 1986). And only panels can give information about the gross change behind a net change (Kish, 1966). Only panels permit studies of individual changes; these may be needed not only for counting the frequency of changes, but also for research on the dynamics of causation and relationships.Longitudinal data can be used to determine causal order of behavioral relationships between two correlated variables (Hensher, 1986). However, lagged causation should not be viewed as the main causal force: simultaneous causation can often be the main link.A panel nearly always measures change with greater precision than an RCS (Kish, 1965). The precision of an estimator of change is measured by the variance of the difference:Var(X1 – X2) – VAR(X1) + Var(X2) - 2ρ[Var(X1)Var(X2)]1/2Where ρ is the product-moment correlation between X1 and X2.With independent (i.e. RCS) samples, ρ is zero. In a panel study ρ is the correlation between the individuals’ responses on the successive occasions. Since the correlation is usually positive, this lowers the variance of the change for a panel study, giving added power of inference.Multi-wave panel or RCS designs enable a more confident conclusion about causal relationships than before-and-after surveys (Hensher, 1986). Multi-wave designs also enable detection of transient effects, subject to the length of time between surveys. Longitudinal designs provide improved evidence on the temporal ordering of variables since no effect can precede its cause (Hensher, 1986). Panel surveys are useful to monitoring the modification in mobility caused by the change in the system (Kitamura, 1990). Panelists are sampled to include individuals (or households) that are influenced by changes in the system (possibly along with individuals that are not influenced as control group members). Repeated observation of the same respondents implies that unobserved contributing factors are well controlled, facilitating more precise measurement of behavioral changes. The direct observation of individuals across time reduces the possibility of being confounded by the typical strong correlation among possible contributing variables, and facilitates the identification of cause-effect relationships. By making the previous wave form available to panelists, it is possible to have a supplementary editing phase, in which certain pieces of data were corrected. Hensher (1986) found a surprising extent of misinformation of some questions, which would not be identified in an SCS. The age of the respondent and other household members was the most inaccurate.Continuous surveys can yield additional information about variations that occur between the periods (Kish, 1966). It is possible to estimate seasonal and secular trends, and to detect the effects of irregular or sudden changes in the predictor variables. They can provide up-to-date information to facilitate and speed decisions that depend on knowledge of fluctuations in the survey variables. The sum of continuous surveys over the entire period under investigation can lead to better statistical inference than a single, concentrated, one-shot survey (Kish, 1966). Probability selection of time segments from an entire interval permits statistical inference from the sample to an average condition over the interval. On the contrary, inference from a “typical” time segment on a one-shot survey to an entire interval demands judgments and assumptions about the nature of variation, or lack of it, over the entire interval. The choice of a single time segment is exposed to the risks of seasonal, secular, and catastrophic variations, known or unknown. Panel surveys present lower costs per interview than RCS surveys (Kish, 1987). First, 22.1.1.2 Drawbacks Time series formed by registers or records present limited extent, accuracy and availability (Kish, 1987).A wide range of issues rises when moving from an SCS to longitudinal data. These issues include missing data (sample selectivity), attrition, decision lags, habit and the dynamics of information accumulation (Hensher, 1986). Two-wave panel and RCS designs have severe weaknesses due to the limited observation before-and-after any change and the inability to distinguish between quite different underlying models for the data (Hensher, 1986).22.2 Types of Longitudinal Surveys Traffic counting (traffic flow) are techniques which constitute important longitudinal (repeated cross-section) data sources. Because of their very specialized nature, they are not discussed in this section.It is convenient to differentiate time series and longitudinal data. According to Hensher (1986), time series usually refer to periodic data bases used by economists studying the macro-economic relationships. Time series data commonly defines time as the unit of analysis, whereas longitudinal data defines the unit of analysis as the individual or household.Time series can be formed by registers, records or direct observations (Kish, 1987). Registers refer to data kept for some administrative use (population, taxes, etc.)Longitudinal data need not to be generated solely by over-time designs. Retrospective reports and prospectively focused behavioral aspirations (the latter from a single cross-section survey) can provide longitudinal data without longitudinal design. 22.2.1 Repeated cross-sections/samples, time sampling Repeated cross-sectional (RCS) designs measure the travel behavior or attitudes of the population over time by repeating the same survey on two or more occasions (Tourangeau et al, 1997). During each time period, a separate but comparable sample of units is drawn from the population and asked to complete the survey. Each sample member completes the survey once, unless they are selected by chance into more than one sample.Because the field procedures, survey instruments, and samples are comparable from period to period, designs of this type allow for comparisons among and between measurement periods. They are ideally suited for assessing period trends in behavior at the population or other aggregate levels, and are often used to monitor changes in the population as a whole or in various subgroups within the population, such as those defined by demographic background characteristics.However, they provide no direct information on change at the level of the individual sample member since each measurement period relies on a distinct sample of households or individuals. Like one-time cross-sectional surveys, they measure cross-sectional variation in travel behavior, but at two or more periods in time instead of at one.Hensher (1986) argues that the interest is specifically in identifying the processes associated with explaining changing preferences and values, an RCS design may be more suitable. Advantages: - Comparisons over time can be made within homogeneous groupings. - Helps to avoid “panel conditioning”, a situation where a panel member becomes familiar enough with the questions that he begins to alter his behavior and/or his survey responses. - Helps to avoid panel attrition problems due to apathy, burden, etc. Disadvantages: - Unable to measure changes from an individual perspective. - Cannot aggregate data for an individual over time. 22.2.2 Pseudo-panel analysisThe pseudo-panel approach is a relatively new econometric approach to estimate dynamic demand models. A pseudo-panel is an artificial panel based on (cohort) averages of repeated cross-sections (Dargay, 2002). The cohorts are defined based on time-invariant characteristics of the households and extra restrictions should be imposed on pseudo-panel data before one can treat it as genuine panel data. Using the cohort data over a number of periods, one could distinguish long run and short run effects while allowing for heterogeneity between the cohorts. In this way, one is able to overcome the deficiencies in both the static models and aggregate time series.Continuous surveys22.2.3 Panel surveysThis survey type repeats measurements on the same set of individuals or households over time.Advantages:· Ability to capture detailed behavioral changes over time.· Can estimate net changes with greater accuracy than when using a repeated crosssection design.· Sample can be aggregated over time by combining data from several waves.· Can measure gross change while repeated cross-sections can measure only net changes.· Contributing patterns to the decision process can be observed.· Expense can be spread over a long period of time – easier to fund.Disadvantages:· Response bias is created due to attrition of the survey sample between waves. This can potentially lead to misleading conclusions.· Panel conditioning and fatigue can occur through time. Conditioning occurs when respondents are repeatedly subjected to the same survey over time. Fatigue can occur when the survey is too long and burdensome.22.2.3.1 Before-and-after panel surveysBefore-and-after designs are commonly used in Transportation surveys to study the impact of transport services and policy on travel behavior, attitudes, and safety (Tourangeau, 1997). In studies of this type, the phenomenon of interest is measured before and after a change in services or policy to assess the impact of the change. Examples of such studies include:a) Assessments of the impact of new legislation on travel behavior (e.g., reduction in trip frequencies following the passage of telecommuting laws), b) Evaluations of the effects of improvements to the transportation system (e.g., reductions in fatality and injury rates following the construction of roadside barriers), and c) Examinations of the impact of new technologies on traffic flow patterns and attitudes (e.g., changes in travel behavior and attitudes following the introduction of changeable message signs or Advanced Traveler Information Systems).It is important to distinguish between before-and-after and multi-period (more than two survey waves) RCS or panel surveys. The latter consist of more than two survey waves. As it is explained later, only multi-wave surveys allow us to track medium and long-term dynamics. 22.2.3.2 Multi-period panel survey

Surveys consisting on three or more waves of data collection from the same individuals are considered as multi-period panel surveys.

22.2.3.3 Cohort panel surveys

Cohort studies focus on population sub-groups that have experienced a certain event in a given period - for example, birth cohort, marriage cohort, divorce cohort. 22.2.3.4 Panel surveys with refreshmentsThe need to introduce new respondents into the sample arises in the course of a panel survey in order to (Kitamura, 1990): a) properly reflect changes in population characteristics; b) make up for the loss of households due to attrition, and c) to provide a reference group to account for panel conditioning effect.22.2.4 Split panel surveysA split-panel design combines a panel sample with a RCS survey (Kish, 1987). Therefore, a new sample is recruited coinciding with each panel survey wave. The panel yields individual changes, and the non-overlapping samples can be accumulated into larger samples; and the combined sample provides the partial overlaps best for current estimates and for net changes. One important advantages of the split-panel design is the possibility of carrying out methodological comparisons and checks of the panel against the changing samples.Advantages: - Provides the best estimate of net change. - Incorporates the benefits of panel surveys and the large sample size of cross-sectional surveys. - Parameter estimations can be made for a distinct point in time using the non-panel group. Disadvantages: - The expense is high due to the many samples. - Two separate surveys must be conducted at the same time. 22.2.5 Rotating panel surveysMixed designs are possible to take advantage of the benefits of each of the three basic survey strategies. A rotating panel design limits the time a respondent participates in the survey, and new respondents are recruited every survey wave. Any two consecutive samples results in intentionally partial overlap. In this case, the sample size remains stable over time and the representativeness of the results is maintained.Advantages: - The potential bias due to non-response, conditioning, and stagnation is minimized. - More precise estimates at a distinct point in time are given than with a repeated cross-section. - This is a better design for comparison of mean parameter estimates over time than with a repeated cross-section. Disadvantages: - Not useful for the aggregation of samples over time. 22.3 Attrition and Other Specific Sources of Bias

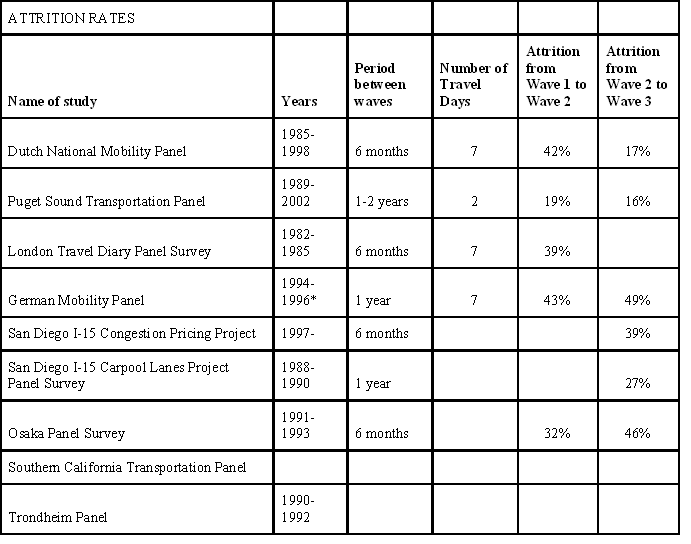

Longitudinal designs (especially a panel) have all the sources of bias associated with design, execution and data analysis of a single cross-section plus extra sources.The most important of the specific source of bias in a panel survey is attrition (loss of respondents after each survey wave). Other bias come from panel conditioning (effects of the panel on the answers and/or behaviour of respondent) and stagnation (sample is no longer representative of the population).22.3.1 Definition and causes of attrition in panel surveysThe hard core of panel attrition is defined by unit non-response of eligible persons or households that occurs after the first wave of a panel (Rendtel, 2002). Kitamura (1990) gave a similar definition for attrition as the dropping out of panel participants in later waves of survey. The concept of non-response is usually used only for cross-sectional surveys and for the first wave of panel surveys.The reason for the unit-nonresponse from the second survey wave may have different sources:-Failure in tracing mobile respondents.-The field agency did not get into contact with the target person.-The target person may be ill and therefore not able to respond.-The target person is no longer willing to cooperate-There are some losses in a panel that should be distinguished from panel attrition:-Demographic losses due to death.-People no longer belong to the sampling-frame and move abroad or into institutions.-Losses induce by sampling design: rotation groups with restricted participation length or “non-sample” persons who are not followed if they separate from the “sample” persons.There are cases where attriters return to participation. Such a participation pattern is often called “temporary drop-out”. However, the reasons for the occurrence of these are quite different:-Persons who are ill and unable to participate recover.-The field agency starts a second try after non-response in the previous panel wave.-The field agency tries to convert attriters after a longer interval of non-participation.

The design of the panel survey also affects the attrition rates. The Dutch National Mobility Panel (DNMP) was a general purpose panel survey that begun in 1984. The respondents filled in a seven-day travel diary twice a year, except in the fourth and in the eighth waves (van Wissen and Meurs, 1989). After the first year of data collection, about 42 percent of the original respondents abandoned the panel. One of the reasons for this attrition was because the second survey wave was carried out using mail (except the refreshment respondents selected in that wave who were interviewed in person). If all households that failed to send the required information in the second wave had cooperated if approached personally, the conditional probability of attrition in wave 3 would have been of 30 percent (Meurs and Ridder, 1997).The London Travel Diary Panel Survey was implemented to provide information on the travel patterns of people within the Greater London area (Terzis, 1988). From 1982 the survey was conducted twice a year up to autumn 1985. Respondents were asked to complete a recruitment questionnaire and a 7-day trip diary. Face-to-face interviews were used only in the first wave, while a postal mail was utilized from the second one. The attrition rate in the second wave was higher than the non-response in the first wave: 38.7 percent and 20 percent, respectively (Stokes and Goodwin, 1988). In a two-wave panel survey of commuter route choice behavior in Los Angeles, California (Abdel-Aty et al., 1994), 944 respondents were recruited using random-digit telephone dialing. Twelve months later, almost 40 percent of the members of the original panel could not be reached for computer-aided telephone re-interviews. The primary cause of attrition was the inability to locate or re-contact first-wave participants. Only 3.0 percent of the first-wave respondents declined continued membership in the panel.22.3.2 Effects of panel attritionPanel attrition causes two problems: the reduction of the effective size of the panel sample diminishes the precision in parameter estimates; in addition, if attrition is non-random, any result from the analysis of the survivors sample will be biased. The first problem can be easily corrected increasing the initial sample size. However, experience shows that attrition is almost always non-random. Attrition bias can be ignorable if the resulting variable of interest is independent of the attrition process. Otherwise it can cause serious problems in the interpretation of the results. Characteristics of Attriters:-Low income-Low education-Smaller household-Single-adult household-Childless household-Retired person household-Household without vehicles-Household without drivers-Relatively young household-Participation in few wavesGolob & Meurs (1986) noted that low-income families, one-person families, families formed by retired persons and households without cars or without drivers tended to drop the DNMP more frequently. Also notable was the association between the number of reported trips and attrition: the mean household weekly trip rate was 51.5 for the households that remained in the panel and 39.3 for the households that did not. The mean weekly trip rate per diary was, respectively, 22.3 and 19.0 for the two groups.The Puget Sound Transportation Panel (PSTP) was a general purpose transport panel survey initiated in 1989 (Murakami and Watterson, 1990, 1992; Murakami and Ulberg, 1997). Five survey waves were carried out with an annual frequency. Households were contacted by phone and family members over 15 years old completed a 2-day trip diary they received by mail. About 19 percent of the original respondents did not participate in the second survey wave. This attrition rate was maintained in the following survey waves, so that about 37 percent of households from wave 1 abandoned the survey and almost half (45 percent) of the original wave 1 household did not make it through the completion of wave 4. This confirmed the tendency reported in other surveys, that low-income households, single-adults households, childless households and relatively young households tended to drop out after the first wave. In addition, considering the usual mode of travel, both SOV (single-occupant vehicles) and transit households had a lower rate of attrition than carpool households. The German Mobility Panel (GMP) was a national rotating panel where each panelist completed a seven-day trip diary (Lipps and Chlond, 2003). The respondents stayed in the panel during three waves and then they were replaced due to conditioning effects. The attrition rate in the second wave was 43.1 percent for the first rotation group in 1995. Although the second rotation group presented a higher attrition rate in its second wave in 1996 (56 percent), the number of abandonments in the second wave tended to decrease in successive rotation groups. Thus, the attrition rates for the third, the fourth and the fifth rotation groups were respectively 27.1 percent, 33.3 percent and 22.1 percent. Persons aged 18-25 and those who presented a slightly lower number of trips tended to abandon the panel.In the San Diego I-15 Carpool Lanes Project Panel Survey, telephone surveys were conducted three times during 1988 through 1990 at approximately one-year intervals (Golob et al., 1997). It was found that younger respondents and those who work away from the CBD tended to leave the panel. Also, those respondents who chose to rideshare, commuted during both morning and afternoon peak periods, and rated I-15 mainline traffic conditions as good in the first wave, tended to participate in the subsequent panel waves. However, the panel sub-sample appeared to be statistically representative in terms of its ride-share behavior and perception of traffic conditions.Hensher (1986) also found that attrition was related to occupational status, driving license holding and various measures of vehicle use in the Automobile Demand Project. Brownstone and Chu (1997) showed that the attrition process in the Southern California Transportation Panel, a study of commute behavior, was correlated with the commute mode choice.Kazini et al. (2000) described panel attrition about 33 percent per wave in the San Diego I-15 Congestion Pricing Project. Attriters were characterized by slightly lower income and shorter commuting distance.The Trondheim Panel was carried out to monitor the impact on travel behaviour of an electronic toll ring. Polak (1999) described an attrition rate of 38.3 percent and found that attrition was significantly related to a wide rage of socio-demographic factors: households with more workers and children, higher levels of car ownership and higher educational attainment were more likely to continue in the panel. Conversely, households with lower incomes are more likely to drop out.And in the South Yorkshire Panel, a general travel behaviour and public transport use study, somewhat less than half the original sample remained in the panel after three waves. Polak (1999) found that attrition in this case was substantially independent of socio-demographics. However, attrition seemed to be strongly related to the history of a household’s panel participation, with a household’s participation in more than two waves leading to a significantly diminished probability of its attrition.22.3.3 Survey Strategies to Deal with AttritionThe reduction of attrition rates can be achieved through several survey strategies: establishing a good initial contact, selecting, training and motivating interviewers, getting a stable relationship between interviewers and panelists, ensuring the currency of the data base records during the panel, communicating frequently with panel members, designing effective tracing mechanisms, and using incentives. Finally, the use of refreshment samples helps both to keep a panel representative of the general population and to compensate for selective or random attrition. 22.3.4 Correcting Attrition Bias22.3.4.1. Types of Attrition ProcessesIn the general case, the attrition process depends on both observed and unobserved variables. This is called non-ignorable missing data mechanism. Little and Rubin (1987) defined the attrition process through an indicator of the observability of each variable. Their likelihood-based approach consists of using joint probability density function of the observed variables in the sample and the indicator of the observability of each variable.The choice of appropriate method of addressing attrition bias is dependent on the process generating the missing values (Dorssett, 2003):Missing-on-observables (MO): there is no unobserved variable that affects both the variables of interest and attrition. Attrition must not depend on the change of the dependent variables before the attrition occurs.Missing-on–unobservables (MU): there are unobserved variables that affects both the variables of interest and the attrition. Changes of the dependent variables have an impact on attrition.In the first case, an observed variable related to attrition has to be found to explain as much as possible the unexplained variation in the regression analysis of the dependent variable. For example lagged values of the variable of interest could be a good candidate. In this case, the more common approach is to use multiple imputation methods. Alternatively, weighting by inverse sample probabilities can be used to restore the sample representativeness.In the MU case, a variable that affects attrition and that has no effect in the regression equation has to be found. Only those variables coming from field-work that were determined by the field agency and are not under control of the respondents are suitable for this purpose. However, these variables usually do not vary across respondents and are not independent from the variable of interest. For instance, changing interviewing modes are frequently encountered in household surveys. However, they are usually based on respondents’ characteristics to achieve a maximum response rate. Different field works modes should be allocated by an experimental design with random assignment to treatments to get useful information.22.3.4.2 Econometric Approaches for Correcting Attrition BiasHausman and Wise (1979) developed a two-step procedure for the non-ignorable case that is in the spirit of Heckman’s sample selection model (Heckman, 1979). This involves estimating the probability of dropping-out and using the results to construct an adjustment term that can be included as a regressor in the outcome equation to correct for the selected nature of the resulting sample. This requires an assumption about the form of the joint distribution of the errors in the selection and outcome equations. As mentioned before, credible implementations also require a suitable instrument: a variable that influences attrition, not outcomes.The multi-wave attrition model of Ridder (1990) is a straightforward extension of the sample selection model. It uses a random effects model for the regression equation and the response model. Meurs and Ridder (1997) used a random effects stochastic censoring model and exploratory methods to estimate the size of the attrition bias in the DNMP. Kitamura & Bovy (1987) developed an econometric model of travel behavior with data from the DMPS. The model system consisted of trip equations for the first and the second survey waves and a probit attrition probability model. Sample weighting factors were built from the latter model. These weights fully utilized the information that the survey results offered and may be preferred over the typical method where observations are weighted according to sample distributions of a few socioeconomic or demographic variables. In addition, these weights reflected unexplained mobility and reporting errors from the first wave. Golob et al., (1997) used an ordered-response probit model used to describe attrition during the three-wave panel survey to evaluate the San Diego I-15 carpool lanes project. A weight was formulated for each respondent and for each wave as the reciprocal of the probability that a respondent would participate in that wave. Kitamura et al., (1993) developed a joint model of choice and attrition behavior using a simultaneous equations system. The estimation of the two-equation system allows the computation of attrition probabilities for each panel participant. To compute joint weights for the PSTP, a bivariate probit model of initial choice behavior was estimated. The model indicated that initial choice and attrition behavior were independent of each other. Attrition probabilities could, thus, be computed as univariate binary probits. Winter (1983) and Hensher and Bodkin (1986) have investigated attrition bias using a model based on the binary logit model and concluded that household socioeconomic and demographic variables alone (the typical x-variables) are not adequate descriptors for determining panel dropout probability and a basis for replacement. While these variables may ensure a representative panel in term of such variables it does not do so in terms of behavioral variables that relate to the real issues under study (for example, vehicle use and ownership in the automobile panel). Hensher (1987) incorporated the fully range of types of influence on participation using a discrete-choice model specification. This model can produce participation probability weights for participating respondents that ensure a representative panel.- (Soft) non-response- Panel effects: conditioning/fatigue/seam effects22.3.5. Panel conditioning, fatigue and seam effects22.3.5.1 Panel conditioning and fatigueThe fact of participating in a panel survey may influence the respondent’s perception, attitudes, or even behavior itself (Kitamura, 1990). Repeated exposure to similar questionnaires may affect responses. For example, respondents may recall their earlier responses and attempt to be consistent in repeated surveys. This is called panel conditioning or time-in-sample effect (Tourengeau et al, 1997).Panel fatigue may be viewed as a special case of panel conditioning in which a decline in reporting rate and accuracy is observed in later waves of a panel survey.Fortunately respondents tend to forget the issues that were raised in an interview. So one way to counteract panel conditioning is to give the panel members enough time to forget about the last interview (with the same question). This may be realized by bringing down the interviewing frequency or by changing (part of) the questionnaire for every measurement (van den Pol, 1987). Panel conditioning bias may also be corrected by acquiring a large (unconditioned) refreshment sample and using it as a reference group. 22.3.5.2 Seam EffectAnother kind of reporting error may affect panel surveys that collect information about the entire period between rounds of data collection. In such surveys, respondents might be asked to report the amount they earned in each month since the prior interview. In these types of designs, there is a tendency for respondents to report changes as occurring at the beginning or end of the time interval between rounds rather than at other times covered by the interview. Changes in salary, for example, seem to cluster in the first month covered by the interview. This pattern of reporting is called the seam effect; it reflects the effect of faulty memory for when changes took place (Kalton and Miller, 1991).22.3.6. StagnationOver time, the profile of the panel may no longer fit that of the population as a whole. For example, the group is constantly aging and income characteristics will likely change. As panels are updated, care must be taken to ensure that the update process is statistically sound. Methods must be used that efficiently maintain a representative panel.22.4 Duration of Longitudinal SurveysThe total duration of a longitudinal survey should be long enough to pick up behavioral changes (Hensher, 1986). This period varies according to the topic under study. As a general rule, the period of each wave should be directly related to the variability of the choice process under study; for example, one year for a study of the dimensions of auto demand; hourly for city traffic flows; and monthly for recreational travel. If the time between observations does not correspond to the actual causal lags, the longitudinal design may be insensitive to important causal interactions (Hensher, 1986). Short intervals between survey waves relative to the frequency of behavioral changes will lead to redundant data in which few changes will be observed. On the other hand, if intervals are too long, some behavioral changes will be over-looked (Kitamura, 1990). To overcome this problem a possible solution is to have a flexible period between survey waves. The Osaka panel survey (Iida et al, 1992) used increasing intervals between survey waves from 1.5 months to one year to study the effects of travel time information system on driver behavior. They assumed that the speed of change decreased as time went by. Another consideration affecting the spacing between rounds is the memory burden imposed by the data collection. Some panel surveys collect a continuous record for the entire period between rounds. In such cases, it is important to keep the spacing between rounds relatively short to reduce the impact of forgetting on the accuracy of the data. Additionally, the higher the frequency of survey waves, the more likely is to appear fatigue effects. On the other hand, when a respondent is interviewed frequently there is little chance that the field work agency will lose track of its respondents because of removals. Taking the previous components together, the attrition rate in one year will generally be at its lowest if the interviewing frequency is about once a year (without considering other factors). Both a weekly interview as well as a reinterview after say ten years will have higher attrition rates.As mentioned before, some panel effects depend on what respondents remember about the last interview. So the interval between interviews should be large enough to forget the issues of the last interview. The length of this interval depends on the issues themselves. Of course, forgetting about the last interview is not the same as not being influenced by the last interview. Panel effects can also emerge if the last interview was forgotten. 22.5 Definition of the Unit of Analysis22.5.1 IntroductionWith any study design, it is necessary to specify a sampling unit. Most personal travel surveys use households as their sampling units. Other possible units for travel longitudinal surveys include persons or housing units.When the sampling unit is a person it is usually clear whether or not to retain the individual in the panel. Generally, persons who leave the population (for example, by moving out of the study area or by becoming institutionalized) are dropped from the sample, but all others are retained. This is the kind of unit of analysis used in cohort panels, where the sample is not refreshed as time goes by; only the initial sample is studied over time.The issues surrounding the definition of the sample unit can get a little complicated when the sampling unit is a family or household. The complication arises because there is no uniformity in definition of the family across different surveys, a family or household, although all are concerned with living together and eating together, sometimes with the pooling of funds. A family or household may also change over time and one must decide which units to keep in the panel. If the unit of analysis is a family, rules for inclusion and exclusion to the panel need to be established. Families may be split because divorce, children born and family size increases, children grow up and leave the family to form another one, etc. Panel sample design should establish rules to consider these situations, assuring that the sample is representative in each wave using refreshment and replacement techniques. The following aspects should be taken into account: · Which changes in families’ composition will lead to be excluded as a panel member? · Definition of operational rules to be followed to determine which households, families or individuals are panel member in each survey wave, and definition of retrospective questions to be asked to those individuals that start their membership mid-panel. 22.5.2 Cross-section familiesA cross-section family definition is determined at one point in time. It is assumed that the family composition does not vary during the research period when retrospective questions are used. It is possible to carry out a longitudinal analysis of a family travel behavior to use a cross-section definition of such a family. For example, panel data can be constructed from a simple interview by asking people to recall previous events. This works best for major events but it is likely to introduce recall biases. 22.5.3 Longitudinal families A longitudinal definition of the family implies to consider only the information collected from families whose composition has remained more or less stable during the research period. If the research period is short, less than a year, the number of families that has changed their composition is small, so this strategy is correct. If the research period is long, a relative large proportion of data will not be included in the analysis. But the information provided by families that has changed their composition is usually the most interesting. There is a need to define a set of rules to maximize the number of initial families that stay in the panel sample. Some of these rules include the following (Dicker and Casady, 1985): · Two families will be considered as one unit of analysis if they share the same individual of reference, or the spouse of the individual of reference. · If the family that includes the individual of reference, or the spouse of the individual of reference, splits into two, the family with more children will be the unit of analysis. · If the application of the previous rule results in two families with the same number of children, then the unit of analysis will be the family with more number of members. · If none of the previous rules are applicable, then it is recommended to join the families randomly. Following this strategy, a family will end its panel membership when its size is reduced to one. And a family will start its panel membership when an individual joins another(s) individual(s). 22.5.4 Dynamic familiesA dynamic family definition considers not only possible variations in the composition of the family, but also the possibility of an increase in the number of families that are members of the sample over the panel survey. A usual strategy for the dynamic family is to collect data about all individuals living in the same household, assuming that at least one of those people had been interviewed in the first survey wave (and the rest of the people fulfill the criteria to be member of the population of study). For example, if a family is formed by a couple in the first wave, and in the second wave they are divorced, the two new families will be included in the sample. Similarly, if an individual joins a family that is a panel member, in the following wave data will be collected from that new member. But if that new member leaves the family, he/she will not be a panel member any more, unless he/she joins a family that already is a panel member. It is also possible that a household splits into two over time. In this case, the new two households will be panel members. This is a very successful strategy to collect data from individuals who leave the initial family/household unit and create a new one. Information from the people sharing the new family/household also is gathered. But the process of tracing and collecting data from those individuals is expensive. 22.6 Survey Methods Many of the advantages of a longitudinal design rest on the assumption that identical measures will be collected at several points in time (Hensher, 1986). This is essential in mapping out the changes in states and characteristics of respondents. Thus, survey methodology design should be homogeneous across all survey waves. The most important survey method that differs from RCS is that methods to improve retention (or reduce attrition) are necessary.Several survey strategies are possible including: · establishing a good initial contact, · selecting, training and motivating interviewers, · getting a stable relationship between interviewers and panellists, · communicating frequently with panel members, · designing effective tracing mechanisms, and · using incentives. · Finally, the use of refreshment samples helps both to keep a panel representative of the general population and to compensate for selective or random attrition. 22.6.1 The Importance of the Initial ContactKitamura (1990) pointed out that in a panel survey as much relevant information as practicable must be collected upon initial contact in order that attrition biases can be corrected later. Hensher (1987) emphasized that the provision of a contact address of a respondent’s close friend or relative during Wave 1 is invaluable for respondent tracing. To optimize response at subsequent waves, the interviewer at the first wave should record all information that may be of help in locating the respondent’s address and in calling at an appropriate time (Morton-Williams, 1993).22.6.2 Selection and Training InterviewersA panel design requires heavy methodological investment in both respondents and interviewers prior to the initial data collection effort (Hensher, 1986). The rewards are received in terms of increased cooperation in the subsequent survey waves. 1. Interviewers for longitudinal surveys may require additional training. Interviewers should understand the special requirements of longitudinal studies, including techniques for obtaining contact information to help locate respondents in the future. Results of earlier panels of a longitudinal survey should be shared with interviewers to increase their interest and motivation (Morton-Williams, 1993). Using well educated and well trained interviewers can result in very low attrition rates. Cundill and Airey (1990) report that only 6 percent of households did not participate in 3 waves of a face-to-face survey completed in 1983, 1986, and 1989. 2. Retaining interviewers over the course of the longitudinal survey has benefits. The retention of many interviewers as possible across all survey waves is convenient to save training costs. Techniques to retain interviewers are similar to techniques to retain respondents: such as letters of appreciation, lottery tickets, or other incentives (Hensher 1986). 3. Continuity between individual interviewers and respondents results in improved rapport and contributes to respondents continuation in the survey. (Morton-Williams, 1993; Van Wissen and Meurs, 1989, and Hensher, 1986).4. The ability of the interviewer to report past survey information, even if the interviewer is not the same person also helps to build the rapport (Hensher, 1986). Respondents felt that such knowledge was evidence that it has been made use of the data supplied earlier and not evidence of a break of confidentiality. 22.6.3 Recruiting RespondentsWhen recruiting respondents for a longitudinal survey, respondents are asked not only to participate in a survey, but in several surveys over time. Lower recruitment ratios are expected in panel surveys than in other type of surveys. The highest possible response is important at the first wave: non-contacts and refusals should be reduced to the minimum by full use of such tactics as sending advance letters, making many calls at the addresses of those hard to contact, reissuing non-contacts and refusals to other interviewers, sending letters to non-contacts and refusers, and so on (Morton-Williams, 1993). The German Mobility Panel (MOP) used a complex recruitment process described below (Kuhnimhof and Chlond, 2003). The objective was to recruit reliable respondents who would participate in a three year period. It consisted of five stages: 1. Commercial market research CATI. Participants in a general-purpose commercial survey were asked about their willingness to participate in another similar study. 2. Stratified Sampling. A stratified sample by household type and car availability of those who were recruited in the first step were carried out to balance socio-demographic biases. 3. MOP-recruitment CATI. The stratified sample was contacted. They learnt for the first time about the MOP survey, and were asked to participate in it. 4. Mailing of further MOP-Information and written declaration of participation. 5. MOP-Participation 22.6.3.1 Internet panels as a potential source for longitudinal survey samplesThere are now many voluntary consumer panels. In some cases, people are provided with Internet service in exchange for their participation in research (Sudman and Blair, 1999). Since their participation will be electronically captured, it can be fed into massive databases that allow tracking and cross-referencing. The motivation for such cyber panels will be a factor related to the increasing interest in highly targeted populations. Research companies will be able to screen these panels rapidly for respondents who meet very exacting requirements. Problems with respondent bias in voluntary, non-representative samples (Rebecca Yalch, TRB January 2008 presentation) Jon Krosnick Stanford project to get a random sample of U.S. population to avoid bias. (Change, LinChiat & Krosnick, Jon A., 2008 “National Surveys Via RDD Telephone Interviewing vs. the Internet: Comparing Sample Representativeness and Response Quality) 22.6.4 Follow-up/tracing Panel MembersTo improve the ability to find panel members over time, the survey questionnaire should include the name and phone number of someone outside the immediate household who would always know where the panel member was. This technique was used in the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics (Duncan, Juster & Morgan, 1987)Another technique to find more current addresses is to mail correspondence using first-class mail, with “Address Correction Requested” printed on the item. Items returned from the Postal Service with new addresses could then be used to update the panel member data base (Murakami and Ulberg, 1997).If survey waves are spaced in 1-year intervals, it is important for mid-wave communication in the form of thank you notes, greeting cards, project summary sheets, and copies of articles in the press about the project (Kitamura, 1990; Tourangeau et al., 1997, Hensher, 1986). These techniques help maintain current address information, and remind respondents that they are part of the research team. On-going telephone contact can be critical to a survey with a relatively high burden. In the Toronto Panel Survey (Miller and Crowley, 1989) 76 transit riders were asked to complete “trip record sheets” for two weeks before and two weeks after a service change. For those who could be contacted by phone, the attrition rate was less than 9 percent. In contrast, the attrition rate among those panelists who could not be contacted by telephone was 75 percent. Today, telephone numbers and email addresses are highly portable, so that finding panel members may be slightly easier, if these contact fields are included. The more widely spaced the waves, the more important are thorough, ingenious search procedures to find panel members. Tracing methods have included “the use of telephone directories, marriages, license registers, military locator services motor vehicle registrations, employers, parents, friends, previous neighbor and current occupants of the sample members’ previous addresses” (Duncan and Kalton, 1987). Personal attention to potential attriters (drop outs) may be necessary to maintain some panel members. Hensher (1986) reports that a direct contact by the study director can convince the respondent of the importance of their participation. In some cases, this may require a personal letter. 22.6.5 IncentivesThe incentives used in the PSTP appeared to be more effective in increasing first wave response rates than in reducing attrition (Murakami and Ulberg, 1997). Households that received no financial compensation in Wave 1 had a higher retention rate in Wave 2 (83.7 percent stayers in Wave 2) than households in the other incentive categories (about 80 percent stayers in Wave 2). In the Toronto Panel Survey two incentives were used (Miller and Crowley, 1989): a lottery ticket to encourage participation in the initial interview given in advance at the transit stop and financial incentives to encourage continued participation in the panel survey. This involved entering all active panel members in a weekly cash lottery. Six winners were selected from this group each week and sent checks for the amounts won. One $50 and five $10 were awarded each week.On the other hand, incentive payments at all waves have been found to reduce data quality (Jones et al., 1986).Although a number of authors indicated the convenience of using incentives (Tourangeau et al., 1997, Morton-Williams, 1993), the effects of incentives and panel instrument updating are still unknown and merit further investigation. 22.6.6 Refreshment SamplesAccording to Pendyala and Kitamura (1997) refreshment samples may be used to keep a panel representative of the general population and to compensate for selective or random attrition. Refreshment samples are a rich source of information. However, refreshment samples must be appropriately weighted on the basis of the sample scheme by that refreshment is recruited.Refreshment samples were drawn in waves 3, 5 and 7 of the DNMP, using the same stratified sample design used for the recruitment of panel households in Wave 1. Strata with heavy attrition were overrepresented in the refreshment samples. (Meurs and Ridder, 1997).To avoid attrition bias, it is extremely dubious to simply replace panel members who drop out of the study (Moser and Kalton, 1979). A general problem with this approach is that since such substitutes are, by their very nature, respondents, they may differ from those dropouts they replace. This can be addressed to some extent by targeting the refreshment sample. That is, the refreshment sample can be drawn disproportionately from those who have low response rates or are likely to drop out. However, it was not possible to know how successfully the dropouts were replaced since their outcomes were never observed. Dorsset (2003) overcame this by considering outcomes held in administrative records for an employment panel survey. 22.6.7 Methods of data collection Taking into account the need of comparability across all survey data of the longitudinal survey, using the same data collection in all survey waves is recommended. But different methods of data collection differ in terms of cost, coverage of the population, likely response rates, and data quality, so this is not always possible or desirable. 22.6.8 Data collection instruments, dependent interviewing, updating questionnaires The results from the first wave of the panel should be analyzed prior to the design of the wave 2 instrument (Hensher, 1986). The first wave of any panel is likely to be the most inefficient with respect to data management. Although no questions should be removed where there is any doubt about their changing influence over time, it is likely that certain questions of no definitive value in wave 1 might be removed to help in reducing length (and hence study costs) and assisting interviewers where length is a concern to the respondents. Examples of adjustments are the deletion of unreliable questions, the clarification of meaning, the deletion of questions of marginal value to enable inclusion of an important question omitted in wave 1, and the removal of all optional questions.The process of updating a panel survey questionnaire is constrained by the need to maintain continuity across waves (Goulias et al, 1990). Despite the existing limitations, Goulias et al (1990) showed that it is possible to improve wording and layout in subsequent survey waves based on knowledge of the quality of earlier responses. 22.7 Sampling DesignLongitudinal or panel surveys track households over time, and collect multiple observations on the same households. However, the panel sample design has three panel problems: the tendency of the sample to get out of date and no longer represent the target population; there may be selective drop-out of panel members; and that panel membership may induce biased answers (van de Pol, 1987). Two alternatives can reduce these panel problems.22.7.1 Rotation Panel SamplesIn a rotating panel design, some fraction of households is held over to be revised, with the rest dropped and replaced by new households. The size of the sample is controlled by restricting the duration of panel membership to a fixed period of number of waves or time. Building up a rotating panel may be done group-wise. Suppose it is decided that respondents should not remained longer than W waves in the panel and that the panel should have n respondents once the process is started up. Then, neglecting attrition, at the time of every wave a new panel group is added to the sample of net size n/W. At a wave W the full sample size n is reached and the first panel group is interviewed for the last time. In practice, one has to draw samples of larger size than n/W, because considerable losses are to be expected due to initial nonresponse and attrition.For rotating panels with a panel membership that lasts several years, it may be necessary to update the panel group for changes in the population. Updating rotation can be applied if a procedure to add new population members randomly into the sample frame (or, even better, randomly within relevant strata) is available. In such a case, updating rotation will be implemented by assigning a random key number to every respondent. Now rotating through such a sampling frame is easily performed by selecting key numbers within a certain range for wave 1 and selecting key numbers within a somewhat different, but largely overlapping, range for wave 2, etc.Updating rotation is not only a good method for keeping the sample up to date, but is also a suitable means to spread the response burden in small population. It will prevent a situation where some units are never sampled, while others are sampled every year.Rotating panel samples are especially suitable to get a sample that is quite up-to-date with the population. Also the bias that may be caused by attrition and panel effects is reduced, but not eradicated. This design has a lower inter-wave correlation, so sample size should be greater than in a pure panel (cohort) design.22.7.2 Updating Panel Samples without RotationFor a random sample of adults (within certain strata), their children will be a random sample too, representing the population inflow of youngsters. So adding the children of panel members to the sample is a good method of updating the panel sample for population inflow. This method is called auto-rejuvenation (van del Pol, 1987). The age limit for entering the sample does not have to be zero. Often children will enter the sample when they become of age. Immigrants will however not get into the sample in the first generation. In the long run, a sample of immigrants into the panel study area should be added to the panel to improve population representativeness. At the same time, others in the study leave (emigrants) and others die, so it is impossible to have a perfect sample over time.On the other hand, a good method to maintain the sample when attrition reduces the size and is likely to be a source of bias, would be to add respondents that have the same scores on target variables as the drop-out respondents. Unfortunately, however there is no sampling frame available with target variables in it (and if it existed no further research would be needed). But new respondents based on auxiliary variables that are relevant, such as sex and the social economic status of the neighborhood, can be added to the panel.Using these auxiliary variables for stratifying the sample into strata or segments it may be assured that in every stratum the same proportion of respondents is interviewed as in present in the corresponding population cell. The rationale behind this method, which is known as quota sampling, is the same as the rationale behind post stratification. It is based on the assumption that respondents and drop-outs have the same (multivariate) distribution on target variables within a stratum. If this assumption is valid drop-outs may be replaced by other people from the same stratum without any resulting bias. 22.7.3 Stratification and over samplingStratified sampling is used when sub-populations vary considerably. Stratification is the process of grouping members of the population into relatively homogeneous subgroups before sampling. The strata should be mutually exclusive: every element in the population must be assigned to only one stratum. The strata should also be collectively exhaustive: no population element can be excluded. Then random or systematic sampling is applied within each stratum. Stratified sampling produces a more representative (and thus more accurate) sample than simple random sampling. This is because stratified sampling ensures that the relative proportions of particular groups of interest represented in the sample are the same as for the population. While this increased representativeness comes at the cost of a more complicated sampling design, the gains are usually worth it.Over-sampling a sub-population is sometimes used by a survey to increase the reliability of the results for that group. This is often used to capture adequate samples of rare or uncommon characteristics, for example, single parent fathers, or transit users in the United States. However, over-sampling is expensive because it takes many more telephone calls to locate these uncommon households. Second, the data need to be weighted to compensate for over-sampling.

REFERENCES

Ampt, E.S. and J. de D. Ortúzar (2004) On best practice in continuous large-scale mobility surveys. Transport Reviews 24(3), 337-363.

Armoogum, J., et al. (2004). “Panel Surveys”. Resource paper presented at the 7th International Conference on Travel Survey Methods. Costa Rica, August 1-6.

Bailar, B.A. (1979). “Rotation Sample Biases And Their Effects On Estimates Of Change”. Bulletin of The International Statistical Institute, 48(2), 385-407.

Berri, A., et al. (1998). “Income Elasticities for Transport Expenditures in Canada, France, Poland and the USA: An Analysis on Pseudo-Panels of Expenditure Surveys”. 8th World Conference on Transport Research, Antwerp, Belgium.

Brownstone, D. and X. Chu (1997). Multiply-Imputed Sampling Weights for Consistent Inference with Panel Attrition, Panels for Transportation Planning: Methods and Application, T. Golob, R. Kitamura y L. Long (Eds.), Norwell, M.A.: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Couper, M. and M.B. Ofstedal (2006). Keeping in contact with mobile sample members. Paper presented at the International Conference on Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys, University of Essex, Colchester, UK, July 12-14.

Dargay, J., J.L. Madre and A. Berri (2000). “Car Ownership Dynamics as seen Through the Follow up of Cohorts: A Comparison of France and the UK”. Transportation Research Record, No. 1733.

Dargay, J.M. (2002). “Pseudo-panel Analysis of Household Car Travel”. ESRC Transport Studies Unit. University College London.

Datta, A.R. (2006). Estimating the value of interviewer experience: evidence from longitudinal and repeated cross-section surveys. Paper presented at the International Conference on Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys, University of Essex, Colchester, UK, July 12-14.

Deaton, A. (1985). “Panel Data from Time-Series of Cross-Section”. Journal of Econometrics 30, 109-126.

Dicker, M. and R.J. Casady (1985). An introductory discussion of issues in the methodology of longitudinal family surveys. National Center for Heath Statistics Working Paper.

DiGaetano, R. and M. Brick (1988). Considering sample weights for families and unrelated individual. NMES Memorandum 2-01700, Westat, INC., Rockvlle, MD.

Duncan, G.J., F.T. Juster and J.N. Morgan (1987). “The Role of Panel Studies in Research on Economic Behaviour”, Transportation Research, 21a (4/5), pp. 249-63.

Elliot, D. et al (2006). Sample design for longitudinal surveys. Paper presented at the International Conference on Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys, University of Essex, Colchester, UK, July 12-14.

Ernst, L.R. (1989). Weighting issues for longitudinal household and family estimates. En Panel Surveys, Kasprzyk, D., Duncan, G., Kalton, G., y Singh, M.P. (Eds.). John Wiley & Sons, New York. Pp. 139 – 159.

Fienberg, S.E., and J.M. Tanur (1986). The design and analysis of longitudinal surveys: controversies and issues of cost and continuity” in Survey Research Designs: Towards a better Understanding of the Cost and Benefits (R.W. Pearson & R.F. Boruch, eds.), Lecture notes in Statistics, 38, Springer-Verlag, New York, 60-93.

Gailly, B. (1994). Dispositif des pondération des individus et des ménages de 1985 à 1992. Document PSELL Nº. 63. Luxemburg.

Gaudry, M. (1975). An aggregate time – series analysis of urban transit demand: the Montreal case. Transportation Research, Vol. 9, August 1975.

Golob, T., R. Kitamura and L. Long (1992). Panels for transportation planning: methods and applications. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Goulias, K.G., N. Kilgren and T. Kim (2003). “A Decade of Longitudinal Travel Behavior Observation in the Puget Sound Region: Sample Composition, Summary Statistics, and a Selection of First Order Findings”. Paper presented at 10th International Conference on Travel Behaviour Research, Lucerne, Switzerland, August 2003.

Goulias, K.G., et al. (1992). “Updating a Panel Survey Questionnaire” in ES. Ampt, A.J. Richardson and A.H. Meyburg (eds) Selected Readings in Transport Survey Methodology, Eucalyptus Press, Melbourne, Australia, pp. 209-236.

Haunberger, S. (2006). The effects of interviewers and respondents characteristics on response behavior in panel surveys – a replication analysis. Paper presented at the International Conference on Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys, University of Essex, Colchester, UK, July 12-14.

Hensher, D.A. (1986). “Longitudinal Surveys In Transport: An Assessment”. In New Survey Methods In Transport. Eds. E. Ampt, W. Brog, A.J. Richardson (Vnu Science Press, Utrech) Pp. 77 – 98.

Iida, Y., T. Uchida and M. Nakahara (1992). Panel survey on the effects of travel time information system in Osaka. Paper to the First U.S. Conference on Panels for Transportation Planning, October 25-27, Lake Arrowhead, California.

Jäckle, A. (2006). Dependent interviewing: a framework and application to current research. Paper presented at the International Conference on Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys, University of Essex, Colchester, UK, July 12-14.

Jäckle, A. and P. Lynn (2006). Respondent incentives in a multi-mode panel survey: cumulative effects on non-response and bias. Paper presented at the International Conference on Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys, University of Essex, Colchester, UK, July 12-14.

Jones, C., M.C. Burich and B. Campbell (1986). Motivating interviewers and respondents in longitudinal research design. Paper given at the International Symposium on Panel Studies at American Statistical Association, Washington D.C.

Kalton, G. and M. Miller (1991). The seam effect with social security incomein the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Journal of Official Statistics, 7(2), 235-245.

Kasprzyk, D., et al. (Eds.) (1989). “Panel Surveys”. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Kuhnimhof T. and B. Chlond (2003). Selectivity and Non-Response in the German Mobility Panel: Selectivity Impacts on Data Quality due to Non-Response in Multi-Stage Survey Recruitment Processes. Workshop on Item Non-response and Data. Quality in Large Social Surveys. Basel, Swirtzerland.

Kuhnimhof, T., B. Chlond and D. Zumkeller (2006). Nonresponse, Selectivity and Data Quality in Travel Surveys - Experiences from Analyzing the Recruitment for the German Mobility Panel“, in: Transport Research Board (Hrsg.), Travel Survey Methods, Information Technology and Geospatial Data, Transport Research Record, No. 1972, 2006, ISBN 0-309-09981-1, S. 29-37.

Kish, L. (1987). Statistical Design for Research. J. Wiley, New York.

Kish, L. (1985). “Timing of Surveys for Public Policy”. Australian Journal of Statistics, 28 (1), pp. 1 – 12.

Kish, L. (1965). Survey sampling. John Wiley and Sons, NY.

Kitamura, R. (1990). “Longitudinal Surveys”. Selected Readings in Transport Survey Methodology, Ampt, E.S., Richardson, A.J. and Meyburg, A.H. (Eds.), Edited proceedings of the Third International Conference on Survey Methods in Transportation, Washington, D.C. January 5-7.

Kitamura. R. (1990). Panel analysis in transportation planning: An overview. Transportation Research Part A, Vol. 24, nº 6, pp. 401-415.

Kitamura, R. and P.H.L. Bovy (1987). Analysis of Attrition Biases and Trip Reporting Errors for Panel Data. Transportation Research Part A. Vol. 21A, No. 4/5, pp. 287-302.

Lynn, P. and H. Laurie (2006). The use of respondent incentives on longitudinal surveys. Paper presented at the International Conference on Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys, University of Essex, Colchester, UK, July 12-14.

Ma, J. and K. G. Goulias (1997). Systematic self-selection and sample weight creation in panel surveys: The Puget Sound Transportation Panel case, ,Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, Volume 31, Issue 5, September 1997, Pages 365-377.

Madre, J.L. (2003). “Multi-Day and Multi-Period Data” in Stopher, P.R. and P. Jones, Transport Survey Quality and Innovation, Elsevier, England.

Meurs, H., L. van Wissen and J. Wisser (1989). “Measurement Biases in Panel Data”. Transportation, 16, pp. 175 – 194.

McCray, T., et al. (2002). “The Design of a Panel Survey on the Organization of Spatio-Temporal Behaviour in the Quebec City Region”. International Colloquium SSHRC-MCRI & NCE-GEOIDE “The Behavioural Foundations of Integrated Land-Use and Transportation Models: Assumptions and New Conceptual Frameworks”, Quebec, 16-19 June.

Moons, E. and G. Wets (2006). Setting up a continuous panel for collecting travel information: discussion on methodological issues. Paper presented at the International Conference on Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys, University of Essex, Colchester, UK, July 12-14.

Morton-Williams, J. (1993). “Interviewer Approaches”. SCPR, Social and Community Planning Research, Dartmouth Publishing Co: Aldershot.

Moser, C.A. and G. Kalton (1979). Survey Methods in Social Investigation, 2nd Ed., Heinemann Educational Books: London.

Murakami, Greaves and Ruiz (2005). Moving panel surveys from concept to implementation. In P. Stopher and C. Stecher (Eds.) Travel Survey Methods: Quality and Future Directions, Elsevier, Oxford, UK, pp. 399-412.

Murakami, E. and C. Ulberg (1997), The Puget Sound Transportation Panel, Panels for Transportation Planning: Methods and Application, T. Golob, R. Kitamura and L. Long (Eds.), Norwell, M.A.: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 159-192.

Pendyala, R.M. and E.I. Pas (1997). Multiday and multiperiod data for travel demand analysis and modeling. Resource paper prepared for Workshop 5 of Transport Surveys: Raising the Standard, International Conference on Transport Survey Quality and Innovation, Grainau, Germany, May 24-30.

Pendyala, R and R. Kitamura (1997). Weigthing methods for attrition in choice based panels. In T. Golob, R. Kitamura and L. Long (eds) Panels for Transportation Planning: Methods and Applications. Kluwer Norwell, MA: Academic Publishers.

Purvis, C.L. and T. Ruiz (2003). “Standards and Practice for Multi-Day and Multi-Period Surveys”. In P. Stopher. and P. Jones (Eds.), Transport Survey Quality and Innovation, Elsevier, Oxford, UK, pp. 271-282.

Roorda, M.J. and E.J. Miller (2004). “Toronto Activity Panel Survey. A Multi-Instrument Panel Survey”. Paper presented at the 7th International Conference on Travel Survey Methods. Costa Rica, August 1-6.

Ruiz, T. (2002). Attrition in Transportation Panels: a Survey. Paper presented at the 7th International Conference on Survey Methods in Transport, Playa Herradura, Costa Rica, August.

Ruiz, Timmermans and Polak (2008). Analysis of Attrition and Reported Immobility in the Madrid-Barcelona Corridor Panel Survey. Paper presented at the 8th International Conference on Survey Methods in Transport: Harmonisation and Data Quality, Annecy, France, May 25-31.

Ruiz, T. (2001). A review of general and mobility panel survey methodology: some findings. Paper presented at the 6th International Conference on Survey Methods in Transports, Kruger Park, South Africa.

Stopher, P., et al. (2006). A pilot survey of a panel approach to evaluating travelSmart initiatives. Road & Transport Research: [A Journal of Australian and New Zealand Research and Practice]; Volume 15, Issue 2; June 2006; 21-34.

Stopher, P. (2008). The Travel Survey Toolkit: Where To From Here? Keynote Paper presented at the 8th International Conference on Travel Survey Methods, Annecy, France, May.

Stopher, P. and Greaves (2007). Guidelines for samplers: measuring a change in behavior from before and after surveys. Transportation, Vol. 34, nº 1, pp. 1-16.

Sudman, S. and E. Blair (1999). Sampling in the twenty-first century. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27, 22, pp. 269-277.

Tourangeau, R., M. Zimowski and R. Ghadialy (1997). “An Introduction to Panel Surveys in Transportation Studies”. Federal Highway Administration, Chicago, IL 60615.

Trivellato, U. (1999). “Issues in the Design and Analysis of Panel Studies: a Cursory Review”. Quality and Quantity, 33, 339 – 352.

Van de Pol, F. (1987). “Panel Sampling Designs”. In Analysis Of Panel Data. Proceedings Of The Round Table Conference On The Longitudinal Travel Study, May 14-15, 1987. Netherlands Ministery Of Transport And Public Works, Project Bureau For Integrated Transport Studies. The Hague, The Netherlands. September.

Van Wissen, L.J.G. and H.J. Meurs (1989), “The Dutch Mobility Panel: Experiences and Evaluation”, Transportation, 16, pp. 99-119.

Zumkeller, D., et al. (2006). Long-distance travel in a longitudinal perspective – The INVERMO approach in Germany. TRB 85th Annual Meeting Compendium of Papers CD-ROM.

|

|

|

| | | |

|