CHAPTER 23.0 GPS SURVEYS

Note: Components of this chapter come from papers or reports written or presented by Dr. Jean Wolf, Michel Bleimer, Mark Bradley and other GeoStats managers.

For more than a decade, transportation planners and modelers have been waiting for large-scale GPS-based household travel surveys in which GPS data logging devices are used to passively collect objective and accurate travel details with seemingly little respondent burden. Since the first test sponsored by the U.S. Federal Highway Administration in Lexington Kentucky in 1996, slow yet steady progress has been made, with efforts made around the globe, towards this goal.

This chapter describes the three primary applications of Global Positioning System (GPS) technology in household travel surveys and the basic elements of a GPS study. The specific GPS study approach and methodology selected for a given regional, statewide, or national household travel survey should be based on the specific objectives of the overall study and the various primary and secondary uses identified for the GPS dataset.

23.1 GPS Study Options

The majority of GPS-enhanced travel surveys conducted in the United States has involved the deployment of passive GPS logging devices in tandem with travel diaries. The primary purpose of this approach has been to audit trip reporting using diary and computer-assisted telephone (CATI) methods to calculate trip rate correction factors for the larger study sample. If the goal of the GPS component is not to audit traditional reporting methods but rather to replace them, then there are two options available. Both of these methods involve using a GPS logger to capture the core trip details (such as origin and destination location, trip start and end times, travel routes and distances). Then, the completion of these details are provided either by GPS-based prompted recall methods (in which the processed GPS trip data is provided back to the participant by CATI, CAPI, or CASI methods) or by sophisticated algorithms that impute many of the missing variables using other available information.

23.1.1 GPS for Trip Rate Validation and/or Correction of Reported Travel

In this ‘traditional’ application, the focus of the effort is on reported trip rate validation. To meet this object, a sub-sample of households participating in a household travel survey are provided with travel diaries for recording their travel for a 24-hour period and with a GPS data logging device. On the assigned travel day(s), household members record their travel and activities in a diary or log while simultaneously capturing GPS data either in household vehicles (if an in-vehicle study) or by household members of age 16 and older (if a person-based study). The analysis focuses on a comparison of the diary data (typically obtained through a telephone interview, a personal interview, or from the diaries themselves) and the trips detected in the GPS data (obtained through software processing). The results of this comparison can be used to generate customized trip rate correction factors based on certain types of trips (such as short stops made for discretionary purposes) that tend to be under-reported and/or on socio-demographic characteristics of persons or households who most often under-report travel. These correction factors can then be applied to the larger non-GPS sample.

23.1.2 GPS-based Prompted Recall Travel Survey

In a GPS-based prompted recall travel survey, household members under the age of 16 are provided traditional diaries and their details are collected by telephone, personal interview, or diary return. Household members of age 16 and older (if a person-based study) or household vehicles (if in-vehicle study) are equipped with passive GPS data loggers for the assigned travel period. Trip detection algorithms are used to identify possible trip ends and the respondents are presented with trip summaries and maps of the detected travel to confirm the GPS-based trips and to collect supplemental information about those trips which cannot easily be obtained from the GPS data (such as parking fees and size of travel party). This feedback loop can be implemented by web, by telephone, or by mail. One variation of this approach has been implemented on handheld devices (such as personal digital assistants (PDAs) or mobile phones) with the prompted recall component implemented either at the end of each trip or end of each travel day.

23.1.3 GPS-Only Travel Survey

In a GPS-only travel survey, household members under the age of 16 are provided traditional diaries and their details are collected by telephone, personal interview, or diary return. Household members of age 16 or older (if a person-based study) or household vehicles (if in-vehicle study) are equipped with GPS for the assigned travel period. Trip detection algorithms are used to identify possible trip ends. Up to this point, the methodology is similar to the prompted recall approach. However, instead of re-contacting the respondents, sophisticated algorithms impute many of the missing variables using other available information.

Due to technology limitations in earlier GPS studies, vehicle-based approaches were the primary method of obtaining objective, passive travel data. Given major enhancements in wearable (or battery operated) GPS data loggers in the past few years, person-based study options are now available. It is worthwhile to note that the same GPS device can be used for either approach.

The use of one approach versus the other can and should be dictated by the study objectives and approach tradeoffs. For example, in the 2007-2008 Washington DC regional travel survey, the primary focus was on vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and so an in-vehicle approach was implemented; whereas the Chicago regional household travel survey wanted to focus on transit users, so a person-based GPS approach was implemented.

Vehicle-based approaches may result in better information regarding transportation supply-side information (such as route choice, roadway speeds, etc.), but do not capture other travel behavior aspects such as mode choice. Person-based approaches may show significant promise in capturing mode choice, but are subject to other limitations such as higher respondent burden (associated with the need to carry and charge the device) and quality (wearable GPS data can be scattered or ‘noisy’ due to incorrect usage or significant sky blockage).

23.2.1 Vehicle-based Approach

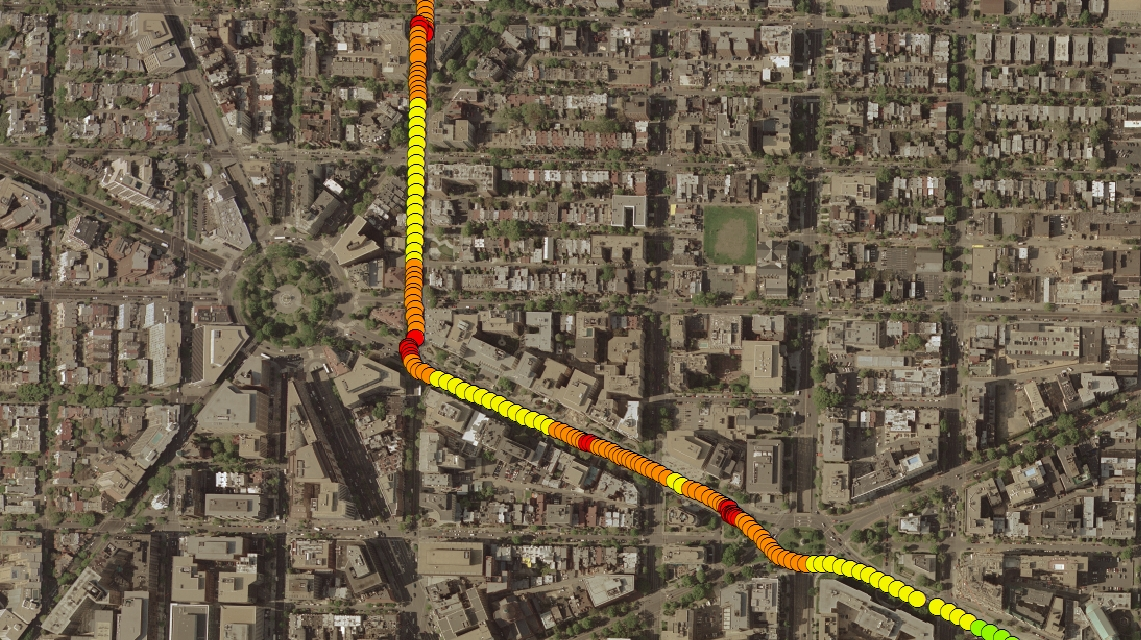

In-vehicle GPS household travel survey efforts to date have shown that respondent burden is minimal as the devices do not need user interaction and they remain in the vehicle, with a clear sky view and reliable power supply, resulting in consistent quality and coverage. Vehicle-based data is easier to process given the higher quality position information and the fact that vehicles travel on roads that exist in GIS networks. Figure 1 shows a vehicle GPS trace through Washington DC.

Figure 23.1 – Sample of Vehicle-Based GPS Data

Although in-vehicle approaches are more suitable to longer duration deployments (given minimal respondent burden and power supplied by the vehicle itself), household travel survey designs using this approach have historically restricted their duration to one or two days. This constraint was driven by higher equipment and data processing costs, and the need for quick equipment turnaround times necessary to support the target GPS sample size. Consequently, these factors have restricted the primary analysis of the data to focus only on a single benefit – that of trip rate auditing. However, given significantly lower equipment and data processing costs, recent in-vehicle GPS studies are opting for longer duration periods (typically one week).

23.2.2 Person-based Approach

In the person-based studies (also referred to as wearable studies) performed to date in the US, all household members of age 16 and older have been provided with wearable devices. Respondent burden is higher than a vehicle-based approach because participants have to regularly or periodically recharge the devices and must remember to wear or carry them (usually by means of clip or lanyard).

GPS data collected in wearable studies tends to be a little messier given the continuous power supply and the ability to collect points while indoors. This scatter in the GPS data requires better software algorithms to remove the noise in the data. In cases where participants forget to carry the device or to recharge the unit, the lack of GPS data cannot be easily distinguished from non-travel behavior. If more than one person in a household receives a GPS device, it is feasible that devices can be inadvertently swapped in the midst of data collection, especially during multi-day data collection periods.

On the other hand, wearable GPS augments to household travel surveys have provided GPS data that have been invaluable in exploring non-motorized or transit travel behavior. Figure 2 shows GPS data collected by a university student who used transit to commute to campus and then walked from class to class. Finding ways to increase participation levels and improving the ease of use and recharging method (or providing a longer battery life) could greatly improve the realized benefits of a wearable GPS approach.

Figure 23.2 – Sample of Person-Based GPS Data

23.3 GPS Data Logger Selection

Costs for GPS data loggers have declined significantly over the last few years, with available devices ranging from basic, inexpensive units (e.g., less than 100 USD) to more costly units that have extra features such as larger storage capacities and better battery/storage management via vibration sensors (which can cost in excess of 250 USD). Although the cost of GPS devices used to be a large cost component of these studies, this is no longer the case. Studies conducted during the past few years with the inexpensive devices have shown that they are reliable and durable—and are suitable for use in household travel surveys. Examples of early generation and late generation GPS data loggers can be seen in Table 1.

Table 23.1 Example GPS Data Loggers

<><><><>

Early Generation | Modern Devices |

|

|

Some studies have tested the use of mobile phones with imbedded GPS to collect GPS data passively; however, these tests have also been limited. This approach faces several challenges, including:

1. If phones are provided to participants, then it may be difficult to get the devices back since they offer an important feature (voice or text messaging). Phones can be expensive, especially with the monthly subscriptions required, and the costs associated with device losses could be a concern. Also, some participants may already have their own phone, so they may not need or want a second phone.

2. If applications are provided to participants to use on their own phones, then software and hardware technical support may be required for a wide range of devices. This approach may also be perceived as invasive, and self-selection bias could be high.

Ultimately, the selection of the device (and device features) will be driven by other study design elements, specifically the study approach itself. For example, a user interface and/or wireless data transfer functionality may be needed if prompted recall methods are desired with short recall time frames, or a simple passive logging device may be fine for either the GPS trip rate auditing or GPS-only approach.

23.4 Other GPS Study Elements

Beyond the study approach, instrumentation approach, and device selection, there are many other elements of a GPS study to be considered when designing the study. This section reviews some of these elements.

23.4.1 Sample Size

For trip rate auditing purposes, the GPS subsample has typically been 5% to 10% of the main sample size. Early pilot studies using GPS-based prompted recall methods or GPS-only methods have had limited sample sizes due to the research nature of the study. However, several recent travel surveys have sought to conduct large-scale GPS components. Among the first large-scale GPS applications is the 2007-2008 French National Travel Survey, which sought one adult volunteer to undertake a GPS component in each of 1,500 households. The Activity-Time Use Survey in Halifax, Nova Scotia, included a GPS component covering 2,000 persons (also one adult in each household). The 2009-2010 Cincinnati household travel survey is scheduled as a 100% GPS study in which all household adult members will be instrumented with wearable GPS devices for three to four days of data collection. The New York City metropolitan area travel survey may have a 10% GPS-based prompted recall sample (1500 GPS households) and the upcoming Jerusalem travel survey is planned as a 100% GPS-only study (both of which are also scheduled for the 2009-2010 timeframe).

23.4.2 Deployment Period

Since most travel surveys collect travel diary data for one 24-hour period of travel, many of the GPS augments to date have also deployed GPS devices for one day. However, variability of travel patterns has always been a concern of one-day travel surveys. Given that a significant portion of the cost of the GPS component goes to equipment leasing and deployment, as compared to the minimal costs associated with processing additional days, consideration is being given to the deployment of GPS devices for more than one day of data collection. In fact, GPS studies conducted in the past few years have begun extending the deployment period from two days up to one week.

Historically, household travel surveys conducted in the United States with a GPS component used in-vehicle equipment to capture vehicle trips and a deployment team that visited the homes in-person to deliver and install the GPS equipment. As the technology has transitioned to smaller, battery-powered units and as the costs of these units has declined, the management, logistics, and labor costs associated with in-person deliveries has increased. Thus, the equipment delivery and retrieval process is transitioning to shipping methods. Of course, shipping methods can easily result in substantial equipment loss as some households may not be motivated to return equipment (even if it has no use to them). Even with these equipment losses, however, shipping methods are still proving to be more cost-effective when all cost components are included.

In some GPS studies, incentives have been offered to GPS participants to encourage participation as well as equipment returns (especially when shipping methods are used for deployment). Results to date indicate that the use of cash incentives does help with both goals.

Once the GPS data is collected by study participants, it is typically downloaded and stored in a project database. At that stage, it is time to convert the GPS point data into trips. Researchers and practitioners in this field have been developing, testing, and refining software that process GPS points, collected by travel survey participants, into meaning travel information. Initial software algorithms focused on the identification of trip ends within these data streams, with more recent activity in this area focused on the imputation of trip details such as travel mode and trip purpose. Trip rate validation studies do not require the imputation of trip details, prompted recall methods may or may not require these details (since they could collect them from the participants), and GPS-only methods definitely require imputed details.

These algorithms can be quite dependent on local or regional transportation infrastructure and transportation options, geographic information system datasets (such a road and transit networks, points of interest, and land use databases), and on the logging rules and variables of the GPS devices. Information collected by study participants during the recruit interview can be leveraged to greatly increase the level of confidence / accuracy of imputed details. This information may include work and/or school addresses for all household members, typical work or school commute travel modes, and presence / usage patterns for bicycles and vehicles.

23.5 Cost Sharing or ‘Repurposing’ Opportunities

GPS data collected in household travel surveys can provide value to transportation modelers, planners, engineers and decision-makers. Typically, the GPS role in a household travel survey is designed for a single purpose with specific parameters that ensure certain objectives are achieved (i.e., trip rate audit). There are a range of other uses of GPS data collected in household travel surveys to support model development, transportation planning, and related areas. Many of these uses can be captured within a single study, thereby maximizing the benefits of the GPS data collection effort while offering cost sharing opportunities among the different user groups.

Model Calibration and/or Validation of Trip Rates, Distances, and Times: Trip rate auditing has historically been the primary focus of GPS add-ons to household travel surveys. GPS data can help identify unreported trips and can be used to generate accurate trip distances and trip travel times. These same accurate trip distance and time data can be used to support model calibration and/or validation through the generation of TAZ to TAZ travel time matrices. These matrices can then be used for comparison to forecasted travel times from the macroscopic model.

Route and Destination Choice Analysis: Route and destination choice analyses are important for understanding respondent flexibility in travel and opportunity for activity. As transportation modeling improvements continue to be implemented around the country, the value of this information may increase. Route choice analysis can also support the supply side as alternative routes and cut-through routes are identified. When combined with land use and other point-of-interest (POI) data, activity opportunity and destination choice within a defined area can be identified.

Mode Choice Analysis: The application of wearable GPS devices in travel surveys can result in the collection of detailed information about multi-modal and non-household vehicle modes of travel. Travel times by mode segment, wait times, and transfer times can all be collected automatically, along with transit system access and egress paths, travel times, and distances.

Model Network Development: Many planning agencies invest significant funds in conducting speed studies to develop network free flow and congested speed estimates. Typically these values are not applied on a unique link-by-link basis but aggregated through look-up tables of link class (road classification) and area type (land use) combinations. GPS data obtained from a household travel survey subsample can provide this information even with limited sample sizes and for walk, bike, and transit speeds as well as the traditional auto focus. For this application, GPS households must be well-distributed in the region with a significant sample size so that the collected trips cover a wide range of road classifications.

Congestion Management: There are several other transportation planning applications for GPS data outside of model development. Congestion management plans in Atlanta, Phoenix, and St. Louis have relied on probe vehicle GPS data for years to identify the location and intensity of congestion on regional transportation systems. GPS data from household travel survey can also serve this purpose. It is likely that sample size and/or deployment period duration will be significant factors in the possible application of GPS in this context, as multiple trips across corridors of interest would be needed. Multi-day GPS studies are particularly useful because regular trips (such as those to and from work and school) can be evaluated to identify average travel time and reliability/variability over time.

Many transportation planners and engineers are focusing on operational improvements strategies to maximize low-cost, high-impact efforts. GPS household travel survey data can provide significant insight into the performance of intersections, turning movements, and signal coordination. Inherent in the GPS trace is information about stop time and control delay for any turning movement conducted by the respondent. An evaluation of multiple GPS traces can start to identify the time “cost” for each movement observed. Identifying bottlenecks and ranking network performance at the intersection and corridor level can provide great assistance in prioritizing transportation improvement projects.

Emissions Modeling: GPS data can be used in emissions modeling to develop and evaluate driving profiles. Emissions models need speed data to generate accurate estimates of vehicle emissions. The driving profiles provide the fraction of time respondents spend at different speed bins. Both Mobile 6.2 and the new MOVES models can use this information to generate estimates. Many regions also use a link-based emissions assessment that is based on the average speed of a road network link and the road volume. GPS can provide the average speeds as well as the variability, thereby giving planners more options for improving emissions estimates. GPS data also provides measurement of time between engine starts. This value is used in estimating the intensity of cold start emission events.

Physical Activity Research: Health researchers have been very active in transportation planning in recent years due to the clear impact of travel behavior on physical activity (and obesity). People who become car-dependent not only have an impact on traffic congestion, but may also have limited physical activity. Wearable GPS devices combined with activity monitors (or accelerometers) have been deployed for multi-day periods in many studies to quantify the levels of physical activity and travel for different populations of interest.

Inclusion of a physical activity component in a household travel survey can serve health research needs as well as provide data for transportation modeling and regional planning needs. The relationship between physical activity and transportation planning is clear, and this knowledge is useful in the development of strategies that promote non-motorized travel. Beyond this, understanding the relationship between physical activity and travel mode should factor into the design of livable communities and other built environment planning activities.