CHAPTER 24.0 QUALITATIVE METHODS

Note: Significant components of this chapter come from (Bradley, 2006; Clifton & Handy, 2003; Goulias, 2003; Grosvenor, 2000; Mehndiratta, Picado, & Venter, 2003; Weston, 2004). Material has been reviewed and updated by Els Hannes, Davy Janssens and Geert Wets.

This chapter explains the added value of integrating qualitative methods in travel surveys. The introduction briefly frames some general aspects of qualitative research. Distinct steps in a research process structure the remainder of this chapter. First, questions and contexts most applicable for qualitative methods are addressed. Next, its actual use, role and timing in travel surveys are discussed. Sampling and data collection issues are treated subsequently, followed by a brief account on qualitative analysis and presentation of research outcomes. To finish, some quality questions in qualitative research are dealt with. Throughout this chapter, numerous references point at both valuable general methodological sources and specific examples of actual surveys of this type.

24.1 Introduction

Originating in the social sciences, the notion “qualitative research” is an umbrella term, covering multiple data collection methods (e.g., in-depth interview, focus group conversation and observation), different analysis approaches (e.g., discourse analysis, content analysis and grounded theory) and a variety of research objectives (e.g., exploration, description, theory development and action research).

Nevertheless, these varying research practices share some common characteristics. First of all, research questions in qualitative approaches focus on an in-depth understanding of the subject at stake. “Why?” and “how?” are central in this type of inquiry, not the traditional, objective and quantitative: “what?”, “who?”, “when?”, “where?”, “how much?” or “how often?” Second, basic data are usually unstructured and rich in detail, such as verbal accounts, pictures and observational data. Sample sizes tend to be rather small. With small sample sizes and hard-to-quantify data, obviously, statistical data analysis is impracticable. Thus, a third distinguishing feature in qualitative research is its inductive approach of data analysis and its different presentation of outcomes.

In this account a pragmatic stance towards different methodological approaches is taken: since different methods produce different types of findings, researchers should simply use methods that suit their needs best. Still, it is important to mention that there is an underlying theoretical debate between positivist and anti-positivist camps influencing the acceptance or rejection of certain research methods. Goulias (2003) frames this discussion in the context of transport studies. Clearly, a fundamentalist attitude hinders integration of research methods.

Compared to quantitative, positivist scientific efforts, qualitative research constitutes a rather marginal phenomenon. This is especially true for the field of transportation research, originating in quantitative applied sciences such as engineering and economics. For instance, in the bibliographic database TRIS Online (NTL, 2009), search terms “travel behavior” and “travel behaviour” generate 4579 records. Further restriction using various search terms related to qualitative methods and subsequent analysis of listed results, shows only 114 unique references report on qualitative approaches to some extent.

A possible explanation of this limited use of qualitative approaches is that these methods are relatively unknown and neglected in mainstream transportation teaching and research practice. If applied, quite often specialized teams treat qualitative research components separately, reflecting traditional research agency structures. And despite small sample sizes, qualitative methods can be time consuming (thus costly), while research outcomes are much harder to define in advance compared to quantitative efforts. Moreover, quality in qualitative research is hard to measure. While quantitative methods can rely on objective statistical verification, qualitative research results rely on subjective interpretation and alternative (contested) readings of “validity” and “reliability”. Added to usual tight research budgets and strict time locks, it is clear why convincing clients to invest in qualitative research can be a real challenge.

Still, qualitative methods are emerging in transportation research, and there is a growing amount of research output. For instance, while the results list of the TRIS Online search mentioned above covers 30 years of qualitative accounts on travel behavior, two third of this output is generated in the last decade. This could reflect a shift in research needs caused by changing transportation policy questions related to travel behavior. While measures of adjusting supply to increasing demand have long dominated both transportation policy and research agendas, growing environmental and health concerns have forced policy makers to make people change their travel choices. Thus, a deeper understanding of individual decision-making with regard to travel behavior is prompted to develop, understand and estimate the impact of travel demand management. As Bradley (2006) shows, in gathering such process data, qualitative methods definitely have a role to play.

24.2 Research Questions in Qualitative Inquiry

A clear distinction between quantitative and qualitative methods is the type of research questions that can be answered by each approach. Denzin and Lincoln (1998, p. 8) put it this way: “The word ‘qualitative’ implies an emphasis on processes and meanings that are not rigorously examined or measured (if measured at all), in terms of quantity, amount, intensity, or frequency. Qualitative researchers stress the socially constructed nature of reality, the intimate relationship between the researcher and what is studied, and the situational constraints that shape inquiry. Such researchers emphasize the value-laden nature of inquiry. They seek answers to questions that stress how social experience is created and given meaning. In contrast, quantitative studies emphasize the measurement and analysis of causal relationships between variables, not processes. Inquiry is purported to be within a value-free framework.”

Which method to choose, depends on research objectives at stake. In travel surveys, this usually relates to increasing understanding of travel-related phenomena. In this respect Grosvenor (2000) points at two essential virtues qualitative approaches can provide: depth and breath. Depth, because underlying motivations and intentional meaning are revealed in its relevant context. Breath, because related issues and their interactions are listed and framed. Furthermore, he suggests that a qualitative approach might be appropriate, if any of the answers to the following questions with regard to the research objectives is ‘yes’:

Do you want depth of insight?

Do you want creativity?

Are you concerned with subtle relationships between the core subject and other (lifestyle) issues?

Are you unsure about the current range of attitudes?

Is the situation changing rapidly within the population you wish to examine?

Are you interested in how ideas are exchanged and developed?

Applied to travel behavior, focusing on an explanation in-depth or revealing an inside perspective is appropriate if one needs to know how people (or specific groups) experience travel. While traditional travel surveys focus primarily on outcomes of travel behavior, here, contexts, motivations and decision making processes are central. At the same time, a deliberate search for breath will uncover the variety of factors, perspectives, characteristics, etc., influencing travel behavior, regardless of their size. For example, think of different meanings adhered to travel, its potential significance in social conduct, various related attitudes or emotions…

Perhaps the best way to illustrate research questions that can be answered using qualitative methods is by pointing at specific examples in literature, referred to throughout this chapter. Note that these instances do not provide an exhaustive overview of all qualitative research conducted in the field of travel behavior. Rather, an arbitrary sample is provided of research in which qualitative methods played a substantial part in developing a better understanding of transportation related issues.

24.3 Timing and Role of Qualitative Methods in the Travel Survey

Theoretically speaking, qualitative methods can flesh out a complete research project, such as in in-depth travel surveys of specific groups. These can be groups that are hard to reach with traditional survey instruments because numbers are small (e.g., the very rich), because specific skills to complete questionnaires are lacking (e.g., illiterates) or simply because they are the usual drop-outs in traditional travel surveys (e.g., the poor). In practice, however, few comprehensive qualitative travel surveys are known to us. Some examples: Handy et al. (2008) explored travel behavior of immigrant groups in California, primarily by means of focus groups. In a similar way, ageing baby-boomers in typical suburban neighborhoods were targeted by Zegras et al. (2008) after segmentation using urban design analysis. Dailey et al. (2007) explored barriers and enablers to cycling in inner Sydney in in-depth focus group conversations. Hjorthol (2005) used in-depth personal interviews to understand motives and frequency of tele-workers in the Oslo region.

More often, qualitative methods are used in combination with quantitative survey techniques. As to timing, three points in the research process can be distinguished: before, parallel to and after a large-scale survey. In each stage, qualitative methods play a specific role.

Early on, qualitative exploration can help to define or refine research questions. This is particularly relevant for new topics or dynamic environments. For instance, Giglierano and Roldan (2001) studied the effects of online shopping on vehicular travel starting with in-depth interviews after discovering a scarcity of prior research on this topic. Besides, exploratory interviews and focus groups are often used to discover the range and wording of meaningful categories that need to be questioned in later, structured data collections. Farag and Lyons, for example, developed an online survey with regard to public transport information use in the UK (2009), based on earlier exploratory interviews and group conversations (2008).

On the other hand, qualitative post surveys are helpful to clarify strange, illogical or unaccountable results of quantitative surveys. This can happen when predefined categories appear to reveal too little differentiation, or response rates in residual categories such as “other” are too high. Also, results might show inexplicable differences with previous or comparable studies. For instance, when travel surveys in Northern California indicated substantial increases in long-distance interregional commuting issues, Lee (1996) further explored this type of travel using focus group conversations.

Finally, qualitative methods can be used at the same time as quantitative surveys. “Mixed method” approaches such as including open ended questions in questionnaires have the advantage of enabling both qualitative and quantitative analysis, but this takes up a lot of time. On the other hand, using interviews or focus groups parallel to large scale questionnaires offers a real voice to respondents. It’s probably the best way to “let the data speak”. For instance, in a two stage survey approach Mackett (2003) examined why people use their cars for short trips. First, respondents were asked to keep a two-day travel diary. From these, short trips by car were identified for detailed discussion at the second stage.

24.4 Qualitative Sampling

In quantitative research random sampling is used in order to be able to generalize results. Qualitative researchers on the other hand, try to build a sample that includes cases selected with a different research focus: to gain in-depth understanding. Therefore, cases are usually carefully chosen. This is ‘purposive sampling’. Depending on specific research goals different strategies exist, but according to Maykut (1994), the most prominent and useful strategy might be ‘maximum variation’ sampling. Here, cases are sought out that represent the greatest difference in that phenomenon. In an account on qualitative survey techniques to explore travel related decisions, Mehndiratta et al. (2003) argue that the sample should be divers with respect to factors hypothesized to affect the travel decisions under study.

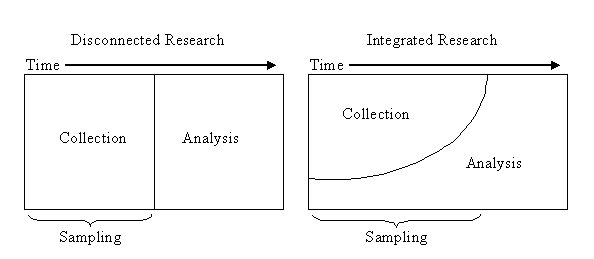

Furthermore, with regard to sample size, the latter stated that four or five individuals sharing each key characteristic should be included in the sample. According to these authors, this typically results in sample sizes that range between ten and twenty people. Indeed, it is a well known fact that sample sizes in qualitative research are smaller than in quantitative surveys. However, much less noted is the fact that in qualitative research, data collection (thus building the sample) and data analysis can be intertwined in an ongoing process until ‘saturation’ in understanding is achieved. This is until typical ‘breath’ and ‘depth’ goals of qualitative methods are met when adding new cases stops leading to new information or additional insights. Ezzy (2003) calls this an integrated research process (see also Figure 24.1).

Figure 24.1 Relationships between data collection and data analysis (Adapted from Ezzy, 2003, p. 62)

Finally, to locate and address respondents, qualitative researchers can use the ‘snowball method’ where one research participant or setting leads to another. An actual application of this method (and previously mentioned purposive sampling) in the field of travel behavior can be found at Hannes et al. (2008). In an exploration of mental maps in daily travel, most important known explanatory characteristics causing variety in daily activity travel behavior are taken into account when selecting the sample: age, sex, education, occupation, driver’s license, possession of car, marital status, household size, parenthood, residential location and mainly used transport mode. Each key characteristic in its own right was represented by 4 to 5 respondents, while avoiding clusters of characteristics as much as possible (e.g. both man and women are present in the sub-sample without a driver’s license). This results in a total sample of 20 respondents. Respondents without a driver’s license and households without private cars were selected to start within the circle of acquaintances of the researcher. Then, according to the snowball method, acquaintances of acquaintances were addressed, gradually filling the predefined matrix of respondents’ characteristics.

24.5 Qualitative Data Collection Methods

In qualitative inquiry primarily unstructured data are gathered: conversations, texts, pictures, etc. Generally speaking, three types of data collection methods can be distinguished: collecting existing documents (1), observation (2), and organizing and recording interviews and conversations (3).

24.5.1 Natural Documents

Existing documents can be private diaries, blogs, internet forum conversations, news, commercial announcements… Some clear drawbacks are that important contextual information is lost, no additional in-depth can be collected if necessary and the origin of the documents might be insecure. A clear advantage on the other hand is that data collection cost can be low because all material is readily available. Besides, ten Have (2004) argues that these ‘natural documents’ are produced as part of current societal processes and not for the purpose of the research project in which they are used. Such data are not affected by interview effects for instance. So far, we haven’t encountered any qualitative research related to travel behavior relying on natural documents.

24.5.2 Observation

Observation as data collection technique is rare in travel behavior research as well. According to Clifton and Handy (2003) the observation of participants in the context of their daily lives could mitigate problems such as self-selection bias, recall and memory issues and behavior modification. They explain that the approach has a rich tradition in ethnographic urban studies, but only one concrete example in the field of transportation is mentioned (op. cit. Clifton & Handy, 2003, p. 11): “Niemeier combined surveys with participant-observer techniques to study the travel patterns of welfare mothers. She conducted surveys at Job Fairs, then followed-up by spending a day with each of a few of the survey respondents, traveling with them throughout the day”. A general methodological introduction on ethnography and field methods can be found in ten Have (2004).

24.5.3 Interviews and Conversations

Without a doubt interviews and conversations are the best known and most often used data collection methods in qualitative travel behavior research. With regard to the actual interview questions, protocols can range from (semi) structured methods such as an ordered list of open ended questions, to unstructured free conversation about a certain topic. As far as the interview setting is concerned, this can be a one-to-one discussion between interviewer and respondent, or a so-called focus group. This is a group conversation with several respondents, a moderator and an observing researcher. There are numerous general methodological accounts on interviewing and focus group research. For instance, Seidman (2006) offers a comprehensive guide to personal interviews. Bloor et al. (2000) discuss how to set up a focus group research in practice and Puchta and Potter (2004) detail how moderators can guide the interaction in focus group conversations.

Related to travel behavior, a discussion and examples of the use of open-ended interviews can be found at Mehndiratta et al. (2003). In the same field, Clifton and Handy (2003) offer a brief methodological account on the application of focus groups and personal interviews, together with a number of examples. One classic and influential model is mentioned explicitly: the HATS (Household Activity-Travel Simulator) developed by Jones et al. (1983). Here, qualitative techniques such as exploratory interviews with households lead to the development of a semi-structured interview technique using a display board to assess the interaction and interdependencies amongst household members in scheduling and executing activity travel behavior. To date, this method inspires household travel surveys (e.g. Stopher and Greaves, 2007) and (Clark and Doherty, 2009).

During face-to-face interviews or conversations, researchers can take notes to store elicited information. These notes can describe observations, such as context, responses to questions, important statements and non-verbal communication. Methodological notes can reflect lessons learned from using the protocol, while theoretical or analytical notes represent emerging insight and preliminary ideas with regard to research outcomes. To relieve observation burden and keep as much information as possible, conversations are usually recorded by voice or video-recorders. Afterwards, audio-files are converted into text files in a process called ‘transcription’. Typing out interview sessions word for word is a cumbersome task (according to Seidman (2006), it takes 4 to 6 hours to transcribe a 90 min. tape), but such verbatim data files are necessary to enable coding and further analysis.

24.5.4 E-research

In the past decades, technological revolution enabled the rise of new data collection methods or ‘e-research’ (Anderson & Kanuka, 2003), such as online focus groups (Rezabek, 2000) and e-mail interviews (Meho, 2006). Clearly one of the advantages of such methods is the avoidance of time-consuming transcription because basic data are text files. But, a major drawback for qualitative research questions is that important contextual information is lost as well. Detailed methodological discussions can be found at the above mentioned authors. In general, it is clear that online research tools can complement rather than replace traditional techniques. Therefore, chosen strategies should be geared to actual research goals and questions. In the field of travel behavior to date there are no genuine qualitative online or internet-based surveys, at least to the best of our knowledge. At most, some open-ended questions are included in traditional web-based questionnaires with predefined categorical answers, (e.g., Klöckner, 2004).

24.6 Qualitative Analysis

While data collection methods are usually quite well explained in reports on qualitative research, descriptions of data analysis often remain brief and hazy. Interviews or focus groups are carried out en then, out of the blue, research findings are presented as if some magic spell generated the outcome. In reality, the analysis process in qualitative research is one of the most difficult steps to undertake. Coding of unstructured data, classifying codes, connecting and synthesizing findings requires a lot from the researcher: creativity and knowledge (to see the theory), meticulousness (to manage a large amount of unstructured data), patience and persistence (to systematically compare, check and double check), introspection and self-criticism (to re-examine critical steps in an iterative analysis process), empathy (to take the perspective of respondents) and a verbal disposition and facile pen (to show results and common findings). For good reason, Wilson (1998, p. 199) notices sharply: “Everyone knows that the social sciences are hyper complex. They are inherently far more difficult than physics and chemistry, and as a result they, not physics and chemistry, should be called the hard sciences. They just seem easier, because we can talk with other human beings but not with photons, gluons, and sulfide radicals.”

24.6.1 Approaches in Qualitative Analysis

Roughly speaking, in general methodological sources on qualitative analysis, (e.g., Bryman, 1994; Dey, 1993; and Ezzy, 2003) two types of analysis can be distinguished: discourse analysis and content analysis. Discourse analysis is concerned with texts and speech as social practice. It pays attention to content in talk, such as topics and meaning, as well as form, such as grammar, structure and cohesion. For further methodological details, see Wodak and Meyer (2001). An application related to travel modes can be found at Guiver (2007), but overall, this type of analysis is rare in travel surveys.

Indeed, the majority of qualitative analysis in travel behavior is some sort of content analysis. Here too, two distinctive strands exist: grounded theory (an inductive approach) and the use of predefined coding schemes (a deductive approach). In analysis using a grounded theory approach, theoretical accounts with regard to the research object emerge from the data (Goulding, 2002). Unlike deductive content analysis approaches, there is no pre-existing theory taken into account. Development of coding schemes is an ongoing process during the analysis. A travel related example is the work of Gardner and Abraham (2007).

The use of coding paradigms on the other hand allows researchers to use a predefined scheme in the coding process, such as conditions, contexts and interactions (Strauss & Corbin, 1998), processes (Becker, 1998) or a table or matrix (Miles & Huberman, 1994). A concrete example related to reasons for car driving is shown by Handy et al. (2005). They develop a framework for exploring the boundary between choice and necessity and then use this framework to guide in-depth interviews and characterize patterns of excess driving.

24.6.2 Coding Qualitative Data

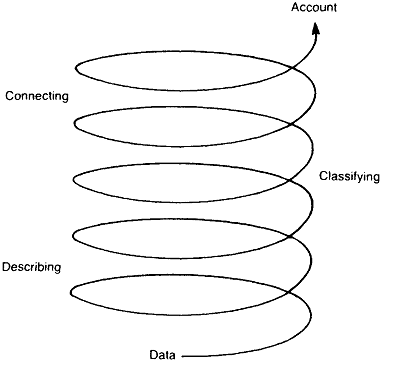

In a case for qualitative methods in transportation research, Weston (2004, p. 2) states: “The key to analysis is coding the data”. The process of labeling, categorizing and sorting data serves to summarize and synthesize observations into concepts and theories. Strauss and Corbin (1998) distinguish 3 steps: ‘open coding’, ‘axial coding’ and ‘selective coding’. Initial ‘open coding’ means breaking down, examining, comparing, conceptualizing and categorizing data. ‘Axial coding’ refers to a set of procedures whereby data are put back together in new ways after open coding by making connections between categories. Finally, ‘selective coding’ means selecting the core category, systematically relating it to other categories and filling in categories that need further refinement and development. Various aspects of analysis are presented sequentially as though analysis proceeds straight through the various coding steps. However, analysis is an iterative process that can be better represented by a spiral (Dey, 1993), see Figure 24.2.

Figure 24.2 Qualitative Analysis as an Iterative Spiral (Dey, 1993, p. 55)

To enhance the qualitative analysis process, specialized software is developed, so-called CAQDAS (Computer Aided Qualitative Data Analysis Software). This software does not automate coding and analysis processes per se, but it facilitates systematic coding, organization and retrieval of documents and data presentation to a large extent. Thus the use of CAQDAS can improve both quality and pace of qualitative analysis. Lewins and Silver (2006) offer a concise overview and comparison of different available software packages. Besides, specialized workshops, such as organized by Lim (2009) can help to learn more about computer-aided qualitative research.

24.7 Presentation of Qualitative Research Results

When qualitative methods are part of an exploratory pre-test, for instance to determine categories to use in large-scale instruments, the outcome of the research process can be a simple list of codes or categories. But, when a written report is needed, it is important to carefully think through the presentation of research results. General methodological elaborations of this stage of the qualitative research process are offered by Margot et al. (2005) and Woods (1999), among others.

In general, typical exemplary verbatim quotes from interviews or conversations are used to demonstrate and illustrate findings. See for instance Hine and Scott (2000) for an example in the field of travel behavior research. Furthermore, developed theory can be presented in lists (usually coding lists), schemes, causal networks or matrices. For instance, Stanbridge et al. (2004) presented results of 11 in-depth interviews with regard to travel considerations in the residential relocation process in a ‘residential relocation timeline’, complemented by typical quotes. Hannes et al. (2009a) draw causal networks to structure and present findings and quotes with regard to daily activity travel decisions. In another paper, they show how a quantitative application, (a Bayesian decision network) can be derived from a qualitative account on travel behavior routines (Hannes, Janssens, & Wets, 2009b).

24.8 Quality in qualitative research

How is quality in qualitative research assessed? Obviously, traditional scientific ‘objectivity’ and quantitative measures such as ‘validity’ and ‘reliability’ are untenable in this context. Therefore, Lincoln and Guba (1985) propose distinct standards for qualitative research such as ‘credibility’, ‘transferability’, ‘dependability’ and ‘confirmability’. But, opponents argue that such a willful secession is harmful for the acceptance of qualitative approaches. A third, moderate view stresses the fact that qualitative researchers should aim at objectivity, but procedures for checking validity and reliability can be adapted to the specific character of the research. Important points of attention in this respect are: ‘thick description’ (researchers should detail all the aspects of the research, including sampling and method of analysis), ‘reflexivity’ (give an account on personal and theoretical perspectives and detail researchers’ role), ‘triangulation’ (test by multiple methods or data sources) and ‘member validation’ (feedback results to respondents). In addition, checklists for quality or validity of qualitative research such as developed by Seale (1999) or Maxwell (1996) offer useful points of attention when considering qualitative approaches, also in travel behavior research (Weston, 2004). Moreover, such systematic checks can help to judge the value of qualitative accounts.

In summary, qualitative methods can be critical complements to quantitative survey methods, including:

identification of categories and multiple choice options to provide in closed-ended questions;

assess user-friendliness of survey instruments and develop and pretest different survey designs;

analysis and categorization of answers to open-ended questions and specifications of residual categories;

additional, specific surveys targeting groups that tend to drop out in traditional surveys;

in-depth understanding of unusual, unexpected, inexplicable survey results;

…

And, of course, they are very useful on their own, for any research question starting with “why?” and “how?”, whenever an in-depth understanding of phenomena is required. Their optimal application depends on one’s study objectives.

REFERENCES

Anderson, T., & H. Kanuka (2003). E-Research: Methods, Strategies, and Issues (1st ed.). Athabasca, Canada: Allyn & Bacon. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from http://www.e-research.ca/index.htm.

Becker, H. S. (1998). Tricks of the Trade: How to Think about Your Research While You're Doing It (1st ed., p. 239). University Of Chicago Press.

Bloor, M., et al. (2000). Focus Groups in Social Research. Sage Publications Ltd.

Bradley. (2006). Process Data for Understanding And Modelling Travel Behaviour. In P. Stopher & C. Stecher (Eds.), Travel Survey Methods: Quality and Future Directions (pp. 491-510). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Bryman, A. (1994). Analyzing Qualitative Data (1st ed., p. 232). Routledge.

Clark, A. F., & S. T. Doherty (2009). Activity Rescheduling Strategies and Decision Processes in Day-to-Day Life. In Proceedings of the 88th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board CD-Rom. Washington: Transportation Research Board.

Clifton, K. J., & S. L. Handy (2003). Qualitative Methods in Travel Behaviour Research. In P. Jones & P. Stopher (Eds.), Transport Survey Quality and Innovation (1st ed., pp. 283-302). Pergamon.

Daley, M., C. Rissel & B. Lloyd (2007). All Dressed Up and Nowhere to Go?: A Qualitative Research Study of the Barriers and Enablers to Cycling in Inner Sydney. Road & Transport Research: A Journal of Australian and New Zealand Research and Practice, 16(4), 42-52.

Denzin, N. K., & Y. S. Lincoln (1998). Entering the Field of Qualitative Research. In Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry (1st ed., pp. 1-34). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.

Dey, I. (1993). Qualitative Data Analysis: A User-Friendly Guide for Social Scientists (1st ed., p. 300). London: Routledge.

Ezzy, D. (2003). Qualitative Analysis: Practice and Innovation (1st ed., p. 200). Routledge.

Farag, S., & G. Lyons (2008). What Affects Use of Pretrip Public Transport Information?: Empirical Results of a Qualitative Study. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2069(-1), 85-92. doi: 10.3141/2069-11.

Farag, S., & G. Lyons (2009). Public transport information (non-)use empirically investigated for various trip types. In Proceedings of the 88th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board CD-Rom. Washington: Transportation Research Board.

Gardner, B., & C. Abraham (2007). What drives car use? A grounded theory analysis of commuters' reasons for driving. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 10(3), 187-200. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2006.09.004.

Giglierano, J., & M. Roldan (2001). Effects of online shopping on vehicular traffic. Mineta Transportation Institute. Retrieved from http://ntl.bts.gov/lib/11000/11800/11825/OnlneShopping.pdf.

Goulding, C. (2002). Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide for Management, Business and Market Researchers (1st ed., p. 186). Sage Publications Ltd.

Goulias, K. G. (2003). On the Role of Qualitative Methods in Travel Surveys. In P. Jones & P. Stopher (Eds.), Transport Survey Quality and Innovation (1st ed., pp. 319-329). Pergamon.

Grosvenor, T. (2000). Qualitative Research in the Transport Sector. Resource Paper for the Worshop on Qualitative/Quantitative Methods. In Proceedings of an International Conference on Transport Survey Quality and Innovation, May 24-30, 1997. Grainau, Germany: TRB Transport Research Circular E-C008: Transport Surveys: Raising the Standard. Retrieved November 30, 2008, from http://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/circulars/EC008/workshop_k.pdf.

Guiver, J. (2007). Modal talk: Discourse analysis of how people talk about bus and car travel. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 41(3), 233-248. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2006.05.004.

Handy, S., Weston, L., & Mokhtarian, P. L. (2005). Driving by choice or necessity? Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 39(2-3), 183-203. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2004.09.002.

Handy, S. L., Blumenberg, E., Donahue, M., Lovejoy, K., Shaheen, S. A., Rodier, C. J., et al. (2008). Travel Behavior of Immigrant Groups in California. Intellimotion, 14(1), 3-9.

Hannes, E., Janssens, D., & Wets, G. (2008). Destination Choice in Daily Activity Travel: Mental Map's Repertoire. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2054(-1), 20-27. doi: 10.3141/2054-03.

Hannes, E., Janssens, D., & Wets, G. (2009a). Does Space Matter?: Travel Mode Scripts in Daily Activity Travel. Environment and Behavior, 41(1), 75-100. doi: 10.1177/0013916507311033.

Hannes, E., Janssens, D., & Wets, G. (2009b). Mental Map of Daily Activity Travel Routines. In Proceedings of the 88th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board CD-Rom. Washington: Transportation Research Board.

Have, P. T. (2004). Understanding Qualitative Research and Ethnomethodology (1st ed., p. 216). Sage Publications Ltd.

Hine, J., & Scott, J. (2000). Seamless, accessible travel: users’ views of the public transport journey and interchange. Transport Policy, 7(3), 217-226. doi: 10.1016/S0967-070X(00)00022-6.

Hjorthol, R. J., & Timmermans, H. J. P. (2005). The Relations Between Motives and Frequency of Telework: A Qualitative Study from the Oslo Region on Telework and Transport Effects. In Progress in Activity-Based Analysis (1st ed., pp. 437-456). Oxford: Elsevier.

Jones, P. M., Dix, M. C., Clarke, M. I., & Heggie, I. G. (1983). Understanding Travel Behaviour. Alderschot, Hampshire: Gower Pub Co.

Klöckner, C. A. (2004). How Single Events Change Travel Mode Choice - A Life Span Perspective. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Traffic and Transport Psychology. Nottingham. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from http://www.psychology.nottingham.ac.uk/IAAPdiv13/ICTTP2004papers2/Travel%20Choice/Klockner.pdf.

Lee, R. (1996). Exploration of Long-Distance Interregional Commuting Issues: Analysis of Northern California Interregional Commuters Using Census Data and Focus Group Interviews. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1521(-1), 29-36. doi: 10.3141/1521-04.

Lewins, A., & C. Silver, (2006, July). Choosing a CAQDAS Package. Working Paper, 5th edition, Surrey, UK. Retrieved November 19, 2008, from http://caqdas.soc.surrey.ac.uk/ChoosingLewins&SilverV5July06.pdf.

Lim, J. (2009). Computer-Aided Qualitative Research 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from http://www.merlien.org/events/program.php?cf=18.

Lincoln, Y. S., & E. G. Guba, (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry (1st ed., p. 416). Sage Publications, Inc.

Mackett, R. (2003). Why do people use their cars for short trips? Transportation, 30(3), 329-349. doi: 10.1023/A:1023987812020.

Margot, E., et al. (2005). On Writing Qualitative Research (2nd ed.). London: Falmer Press.

Maxwell, J. A. (1996). Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach (illustrated edition.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Maykut, P. (1994). Beginning Qualitative Research: A Philosophical and Practical Guide (1st ed., p. 194). Routledge.

Mehndiratta, S. R., R. Picado & C. Venter (2003). A Qualitative Survey Technique to Explore Decision Making Behaviour in New Contexts. In P. Jones & P. Stopher (Eds.), Transport Survey Quality and Innovation (1st ed., pp. 303-317). Pergamon.

Meho, L. I. (2006). E-Mail Interviewing in Qualitative Research: A Methodological Discussion. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57(10), 1284-1295. doi: 10.1002/asi.20416.

Miles, M. B., & M. Huberman (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourceboo (2nd ed., p. 352). Sage Publications, Inc.

NTL. (2009). National Transportation Library - Integrated Search. Retrieved February 13, 2009, from http://ntlsearch.bts.gov/tris/index.do.

Puchta, C., & J. Potter (2004). Focus Group Practice. Sage Publications Ltd.

Rezabek, R. J. (2000). Online Focus Groups: Electronic Discussions for Research. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(1), 20.

Seale, C. (1999). The Quality of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications Ltd.

Seidman, I. (2006). Interviewing as Qualitative Research (3rd ed.). New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Stanbridge, K., G. Lyons & S. Farthing (2004). Travel behaviour change and residential relocation. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Traffic and Transport Psychology. Nottingham. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from http://www.transport.uwe.ac.uk/staff/tp221r%20-%20final.pdf.

Stopher, P. R. & S. P. Greaves (2007). Household travel surveys: Where are we going? Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 41(5), 367-381. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2006.09.005.

Strauss, A. C. & J. Corbin (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research: Second Edition: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (2nd ed., p. 336). Sage Publications, Inc.

Weston, L. M. (2004). The Case For Qualitative Methods In Transportation Research. In Proceedings of the 83rd Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board CD-Rom. Washington, D.C.

Wilson, E. O. (1998). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (p. 384). New York: Vintage books.

Wodak, R., &M. Meyer (2001). Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis (First Edition.). Sage Publications Ltd.

Woods, P. (1999). Successful Writing for Qualitative Researchers (1st ed., p. 158). Routledge.

Zegras, P. C., et al. (2008). Comparative Study of Baby Boomers’ Travel Behavior and Residential Preferences in Age-Restricted and Typical Suburban Neighborhoods. In Transportation Research Board 87th Annual Meeting. Retrieved from http://pubsindex.trb.org/paperorderform.pdf.