CHAPTER 3.0 OPTIONS FOR TRAVEL SURVEYS

Note: Significant components of this chapter come from Joanne Pratt, Martin Lee-Gosselin and Shanna Burbridge

This chapter describes the different types of travel surveys, the general types of survey data typically sought in each type of travel survey, and the available survey methods currently being used for each type of travel survey.

3.1 The Types of Travel Surveys

This manual discusses the most common types of travel surveys used to learn more about (and to model) the behavior of users of highway and transit facilities. Each of the survey types provides a unique perspective for input into travel demand models, so the selection of the appropriate travel survey type should be based on the development or revision plans for the models themselves.

3.1.1 Household Travel/Activity Surveys

Traditionally, the most important building block for urban and regional travel demand models has been the household travel survey. In a household travel survey, respondents are contacted in their homes and are queried about their household characteristics, the personal characteristics of members of the household, and about details of recent travel experiences of some or all household members.

Household travel surveys have been conducted in the United States for more than 40 years, but because of the extensive effort required, most regions have conducted only one or two of these surveys. The first generation of household travel surveys are characterized by those conducted in the 1960s to address the requirements of the FHWA’s 3 C planning process. These surveys were conducted by sampling households in the region and sending survey staff to the households to solicit cooperation and to conduct interviews. In some cases, the survey workers left survey materials, including travel diaries for each household member for an upcoming period of time and then returned to collect the travel information, but usually the surveys asked respondents about recent past travel.

Usually, the primary focus of the household survey was to assemble origin-destination data based on fairly coarse zone systems. The U.S. Department of Transportation’s sample size recommendations for household surveys ranged from one dwelling unit out of 25 for study area populations over one million people, to one dwelling unit out of five for study area populations under 50,000 people. The same guidelines set the range of “minimum sample sizes” to between one out of 100 dwelling units for the largest areas, to one out of 10 dwelling units for the smallest areas.

Most planning agencies developed their four-step transportation demand models primarily from the data that they gathered in their 1960s household surveys. In many cases, these models continued to rely on the 1960s household survey data for the next 20 to 30 years.

The first generation in-home survey method was considered to be the acceptable procedure for household travel surveys throughout the 1970s and the first part of the 1980s, though significantly fewer major household survey efforts occurred in this period than the preceding period.

During the 1980s, planners began to recognize the need for updated household travel data. However, the new household survey methods that survey designers employed were significantly different than the earlier efforts. In the past several years, most household travel surveys have been conducted by using telephone or mail surveys or some combination of the two. In addition, typical sample sizes measured as a percentage of the survey universe have been reduced to one-quarter to one percent of study area dwelling units. This decrease in sample size has lead to very little decrease in the overall accuracy of the survey results because the newer surveys rely on more efficient stratified sampling techniques and because modelers generally apply disaggregate modeling techniques to develop origin-destination data, rather than rely solely on the survey data. Collecting travel data through diaries instead of through recall techniques is now common practice, and many recent surveys have redefined the diary unit from the simple trip to more detailed elements of the trip, or to activities that can be related to trip making.

Several factors contributed to the development of the second generation of household travel surveys in the U.S. The most important factor was the need to reduce the high costs-per-interview and logistical difficulties of the in-home interview. Advances in commercial market research allowed transportation planners to develop alternative approaches. At the same time, developments in travel model research and inadequacies in traditional travel models have lead planners to consider issues such as trip-chaining, activity-based modeling, and time-of-day modeling.

Despite the changes, the household travel or activity survey remains the best source of regional trip generation and distribution data for most regions. It is highly likely that household travel and activity surveys will be central to the development of microsimulation-based modeling systems, like TRANSIMS.

In addition to being used for developing, revising, and updating regional modeling efforts, household travel surveys are being used in the following ways:

· Some transit agencies use household travel surveys to conduct surveys of transit users and non-users in their regions. The surveys are used to estimate transit market share and to assess differences between actual transit users and potential users.

· Agencies have performed household travel surveys in advance of major infrastructure projects to help assess the potential demand and to determine the level of public support.

· Agencies sometimes perform household travel surveys simply to increase their understanding of travel in their regions, and to be able to address specific questions that policymakers may raise.

3.1.2 Vehicle Intercept and External Surveys

Vehicle intercept survey data are used by travel demand modelers for three purposes:

· To provide origin-destination data and other data on trips that come into or go out of the model study area for modeling internal-external and external-external trips (external survey);

· To provide origin-destination data and other data for auto travelers in a particular corridor for sub-area and small area models; and

· To provide origin-destination data and other data for auto travelers crossing important internal cordons, screenlines, and cutlines that can be used for travel model validation.

Unlike the household surveys, these surveys rely on intercepting or observing people in the course of travel. These surveys are conducted by stopping vehicles and then interviewing drivers or distributing mailback questionnaires to them, by observing vehicle license plates and then recontacting the owners of the vehicles, or by tracking vehicle through GPS technology. Traditionally, these surveys have focused on gathering information on the particular trip being made at the time of the intercept with little emphasis on other information. Chapter 7.0 describes the typical procedures used in the collection of vehicle intercept and external surveys.

3.1.3 Transit Onboard Surveys

Transit onboard surveys are similar to the vehicle surveys in that they are intercept surveys and use a choice-based sample population (to be eligible for the survey, the respondent has both decided to travel and to use the particular mode of interest). Transit onboard surveys are generally conducted for two reasons:

· To provide modelers with transit trip origin-destination data and transit rider characteristics, which in many regions is very difficult to obtain from the household survey because transit trips may make up a very small proportion of total trips; and

· To provide transit planners with ridership data that will allow them to analyze changes in service.

Generally, transit onboard surveys collect trip-specific travel data and some limited respondent information. Often, planners are interested in surveying both users and non-users (or infrequent users) of transit services. This is generally accomplished by using a combination of transit onboard surveys and either household travel survey techniques or vehicle intercept survey techniques. Chapter 8.0 describes the issues related to transit onboard surveys.

3.1.4 Commercial Vehicle Surveys

Travel demand modeling for commercial vehicles is somewhat primitive compared to passenger travel modeling. However, the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act's (ISTEA-1991) intermodal planning requirements have added to the importance of commercial vehicle data collection. Some information on commercial vehicle travel can be obtained through household surveys and vehicle intercept surveys, but the only way to accurately analyze the universe of commercial vehicle trips is through a commercial vehicle survey.

Commercial vehicle surveys are used primarily to obtain origin and destination data for trucks, taxis and other commercial vehicles. Recent efforts have also begun to obtain more detailed trip purpose and truck contents information. This information can be used in the development of disaggregate urban commodity flow models. Chapter 9.0 discusses commercial vehicle surveys.

3.1.5 Workplace and Establishment Surveys

Establishment surveys are used to collect travel information about trip attraction sites. These surveys generally collect traveler characteristics and trip origin and destination data. Typically, workplace surveys are designed as intercept surveys where respondents are surveyed as they enter or leave their workplace or another establishment. In some cases, workplace surveys are centrally distributed to employees by employers or employer transportation management agencies. In these cases, the survey method is more of a general population survey, like the household survey.

A special application of the workplace/establishment survey is the special generator survey. Special generator land uses are unique to a region (such as an airport, university, or large shopping mall), or they attract and produce significantly more trips than would be indicated by their employment, square footage, or land area. Since trip rates to and from these sites might be significantly different, surveys of trips to and from these locations can be especially useful. Chapter 10.0 presents descriptions of workplace, establishment, and special generator surveys.

3.1.6 Hotel/Visitor Surveys

In many parts of the country, a large percentage of the daily regional travel is conducted by visitors or tourists to the region. In some of these areas, planners have sought, or are seeking, to develop visitor travel demand models. The household travel or activity survey could be used to account for some of this travel if data are collected from visitors staying in local residents’ homes. However, visitors staying in hotels, motels, or other lodging would elude the household survey, and there are likely to be significant differences between the travel patterns of those visitors staying with residents and those who pay for their accommodations.

Visitor travel could theoretically be surveyed by one of the intercept methods discussed in Chapters 7.0 and 8.0 (transit onboard or vehicle intercept), but collecting the needed trip generation information with these survey methods would be practically impossible. To obtain the necessary visitor data, some metropolitan areas have conducted hotel visitor surveys. A description of this survey method is presented in Chapter 11.0.

3.1.7 Parking Surveys

The latest generations of travel demand models have recognized the importance of parking supply, costs, and subsidies on travel decisions. When detailed parking information is needed, parking surveys are sometimes used. During a parking survey, fieldworkers conduct interviews with, or distribute questionnaires to people as they enter or leave parking facilities, or leave questionnaires on the windshields of parked cars.

Parking surveys are similar to workplace/establishment surveys in that travelers are usually surveyed at the attraction end of their trips, but parking surveys generally seek to collect more detailed information about parking and access issues. Parking survey procedures are presented in Chapter 12.0.

3.1.8 New Types of Surveys

This section needs to be written from these thoughts shared by Joanne Pratt: for "new types of surveys" - it needs up to date info – need to add sources like GPS, Cell Phone, Laptops, Blackberry’s and their role in data collection – for GPS, Martin & Elaine would be the resource for information, for Laptops, Sean Doerghty gave families laptops to fill out their plans for travel – for Cell phone, Joanne remembers that at an Austin conference a couple years ago (may have been a TRB conf, held at Hyatt in AUS), a Japanese researcher had a paper on using cell phone to collect data changes in travel distances as people made arrangements by cell to meet for dinner, then made changes in their plans also by cell – he was capturing travel plans at the source. For cell phones, you literally have a GPS and keyboard in one tool. 3.2 Selecting the Proper Types of Travel Surveys

The selection of the proper types of surveys to use in developing or enhancing travel models should be based on the type of data and sample size required for the models, each survey type’s survey population, the data available from each type of survey, and the cost and complexity of fielding the survey. The cost and complexity of the survey type is related to the actual marketing research techniques needed to complete the survey effort.

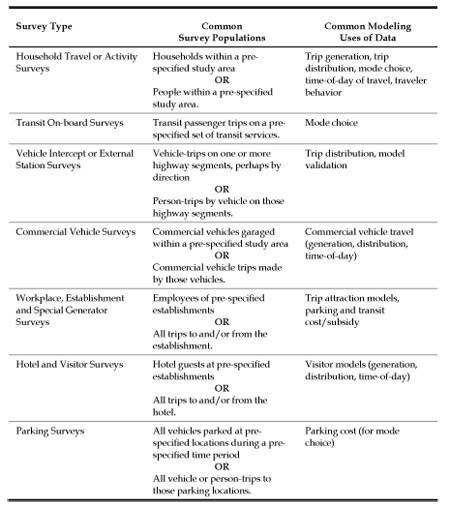

3.2.1 The Modeling Uses of Survey Data and the Survey Populations

Table 3.1 shows the most common survey population or populations and the most common data uses for each type of travel survey considered in this Manual. In selecting the most important and cost-effective travel surveys for modeling purposes, the analyst needs to determine whether the survey type will truly reach the most appropriate population or universe. For instance, it is important to note that the survey populations for the intercept surveys are not the travelers, but instead are the trips themselves. Conversely, the general population surveys, such as the household survey, have populations which are based on the trip-making unit, not the trip . These distinctions can have important implications on the models that are developed with these survey data, particularly when the two types of data are combined.

Table 3.1 Common Survey Populations and Modeling Uses of Different Travel

Usually expansion data can be collected in the survey (or along with the survey) that will allow the modeler to weight the survey results to a different survey universe, but the cost of obtaining these data need to be considered in deciding whether a particular survey type makes sense. For instance, the analysis of vehicle intercept surveys generally requires high quality vehicle count and classification data to expand the survey results.

The most appropriate type of travel survey depends on the data needs of the surveyor. Usually, travel modeling analysis requirements dictate the types of surveys that are needed. Household travel surveys are particularly relevant for current travel models. These surveys can provide information on the number and distribution of trips being made and the travel modes being selected by individuals within households, as well as the household and the individual’s characteristics.

The other survey types (such as activity surveys) can provide specific data that modelers want or need to develop or enhance travel models. The detailed model plan will determine the data needs, and therefore the survey types that are needed.

Of course, there are reasons other than travel model development/enhancement for conducting travel surveys. For instance, transit onboard surveys are often conducted for developing new transit routes or modifying existing ones. Vehicle intercept surveys are commonly used in site impact planning. Surveys developed for different reasons can be, and often are, used in travel modeling efforts, so it is extremely helpful to design and coordinate these surveys with this in mind.

3.2.2 Travel Survey Data

Travel surveys can be used to collect several kinds of information from respondents, including:

· Factual information about themselves or their households or other affiliations (socioeconomic, demographic, employment data);

· Behavioral travel information about one or more trips or travel-related activities (revealed preference travel data);

· Test-of-knowledge information (data used to determine respondents’ familiarity with a particular subject);

· Attitudinal information and perceptions (data from ratings, rankings, or comparisons of actual or hypothetical subjects);

· Opinion information (data gathered from open-ended responses);

· Stated response travel information (stated preference data compiled from tradeoff analyses and other hypothetical choice exercises); and

· Longitudinal information (data gathered from the same or similar respondents over a period of time).

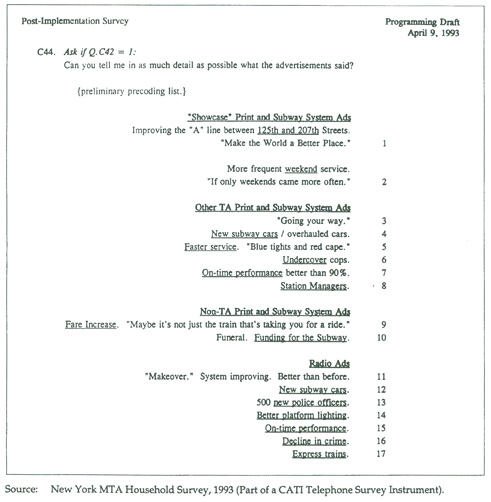

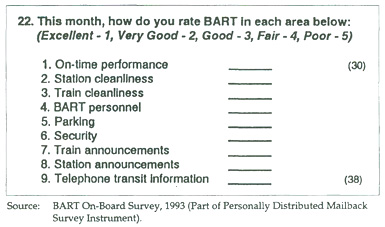

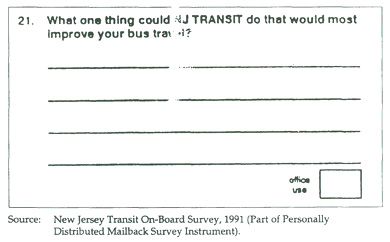

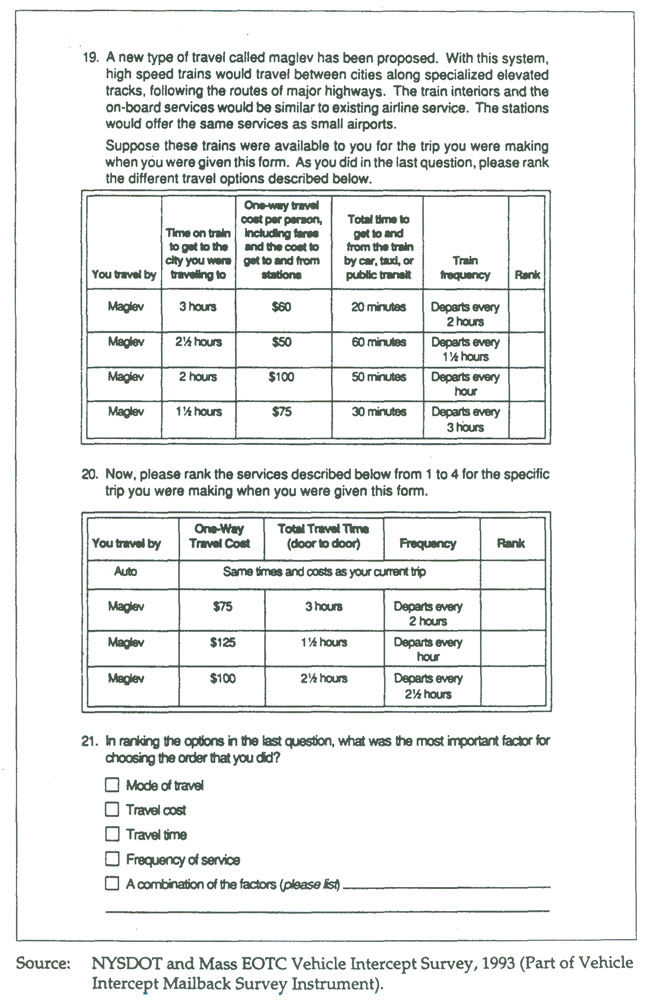

Figures 3.1 through 3.6 show example portions of travel surveys seeking each of the first six of these data types. The seventh type of data, longitudinal information, can actually be any of the first six types, but tracked over a period of time through successive surveys.

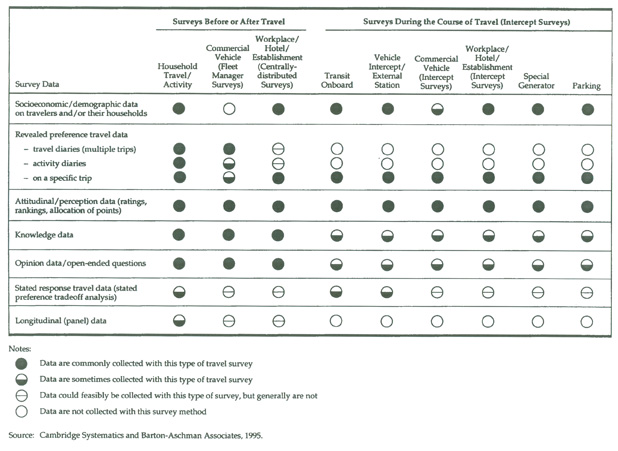

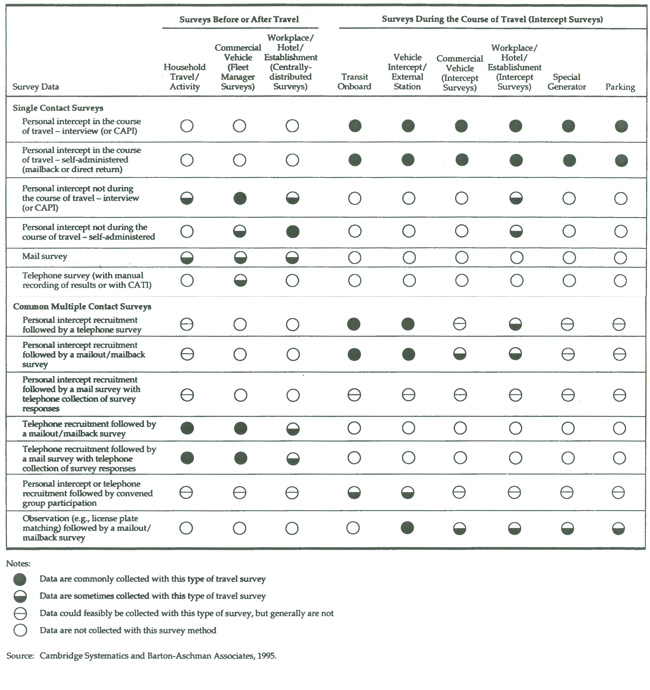

Each type of survey is well-suited to obtain certain types of these data. Figure 3.7 summarizes the kinds of data that each type of survey has been or could be used to collect.

Traveler and household information is commonly obtained from all the survey types, except surveys of freight movement. The best types of surveys for collecting large volumes of these data are the household travel/activity survey and the workplace survey with centrally-distributed questionnaires. These survey types are based on samples of the individuals for which the socioeconomic/demographic data are being collected, rather than the trips that they are making, so frequency weighting can be averted. In addition, when a great amount of these data are needed, the intercept survey methods may be practically inadequate. The two most common survey methods for intercept travel surveys, short interviews of travelers in the course of their travel, and personally distributed mailback questionnaires, have limited lengths so it is difficult to include many socioeconomic or demographic questions in these surveys. Sometimes, the intercept survey types are used as an initial recruitment followed by a household travel/activity survey to obtain the more detailed data.

Revealed preference travel data can be obtained from any of the survey types, but the individual survey types are particularly well-suited for collecting certain types of travel behavior data. Household surveys are commonly used to obtain detailed travel and activity diary data. The ability to contact each household member and the ability to use more complicated questionnaires with this type of survey make it the best choice for collecting household diary data. Commercial vehicle surveys can also be used to obtain diary-type information, but generally the sampling units in these surveys are the vehicles, rather than people or households. Diary data are generally not collected using the other types of surveys because of the length and complexity of the questions, and because not all household members can be easily contacted through these methods.

The other types of surveys are usually used to collect information on the specific trips that respondents were making when they were intercepted or observed. The household and commercial vehicle surveys sometimes also request data on specific individual trips, such as work trips for households, or the last trip of a particular type for a commercial vehicle, but these data are generally obtained with diary-type questions.

Figure 3.1 Example Factual Information Questions

Figure 3.2 Example Travel Behavior Questions

Figure 3.3 Example of Test-of-Knowledge Question

Figure 3.4 Example of an Attitude/Perception Question

Figure 3.5 Example of an Opinion Question

Figure 3.6 Examples of Stated Preference Questions

Figure 3.7 Types of Survey Data Available from Different Travel Surveys

Attitudinal/perception questions are commonly asked on all types of travel surveys. These questions are used to obtain quantitative data that support policy decisions, but the data are generally not used in formal demand models. Test-of-knowledge and opinion data provide less quantitative information to support policy decisions. These data are most easily obtained on longer surveys, since questions of these types often need to be preceded by fairly lengthy descriptions to which individuals are asked to respond. Open-ended opinion questions are sometimes asked at the end of transit onboard, vehicle intercept, and other intercept surveys. The questions are often used to simply allow interested respondents the opportunity to “sound-off.” Some surveyors believe that this opportunity encourages individuals to respond to the entire survey. However, in many cases, these open-ended responses are not even entered or coded.

Increasingly, travel surveys are being used to obtain stated response data (usually stated preference data). These types of data are being obtained in household surveys and in transit onboard and vehicle intercept surveys, but any type of travel survey could be used to obtain them.

Finally, longitudinal data have been and are being obtained in household travel/activity surveys. These data may provide those analyzing it with unique travel behavior insights, including the measurement of how household travel patterns change over time and the determination of the relationship between travel and residential choice.

In the following chapters, specific data items commonly collected by each travel survey type are tabulated and discussed.

3.2.3 Available Survey Methods for Travel Surveys (comment from Joanne Pratt : Maybe under sec 3.2.3 you could note that Technology has greatly contributed to new survey types and that the mobile generation should be addressed)

3.2.4 Personally Administered Interviews

The most traditional survey method is the face-to-face interview, in which trained interviewers approach potential survey respondents, request their participation, and ask them the survey questions. Personally administered travel interviews can take place in one of four ways:

· In-home Interviews – Respondents are contacted and interviewed about past and/or future travel they have conducted. Until the 1970s, this survey method was commonly employed for household travel surveys.

· Personal Intercept Interviews – Respondents are contacted and interviewed in the course of their travel. Transit onboard, vehicle intercept, and some establishment surveys employ this method.

· Workplace Interviews – Respondents are contacted and interviewed at work. Some commercial vehicle and workplace surveys use this survey method.

· Central Location Interviews – Respondents are contacted and interviewed at public locations, including shopping malls that attract a representative sampling of a travel survey’s population of interest. This method is not yet common for travel surveys, but its use is increasing in other surveying fields.

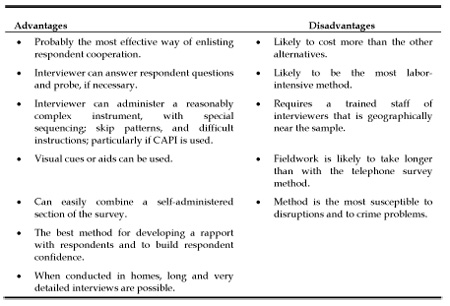

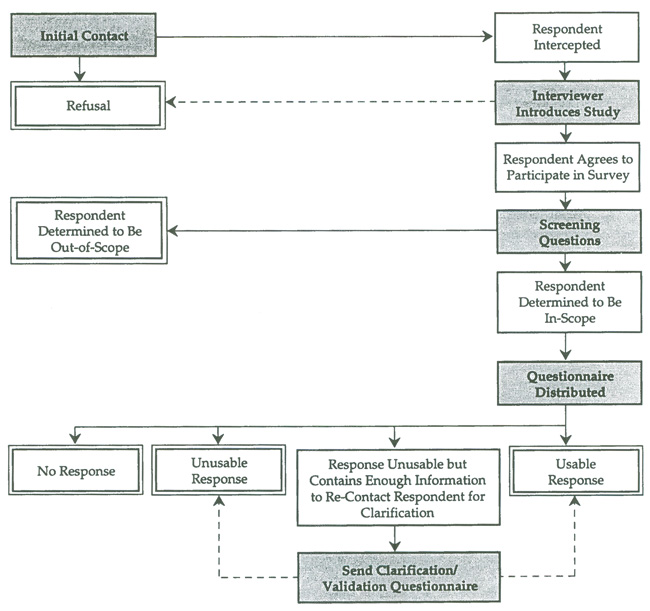

The survey fieldwork procedures for the different personally administered survey methods and for different travel survey types vary, but in all cases the process for interviewing each potential respondent is similar to that which is shown in Figure 3.8.

As Figure 3.8 shows, the first step in the personally administered survey field process is to contact the respondent. This might involve a fieldworker knocking on a person’s door for in-home surveys, greeting a transit rider on a bus or at a station for onboard surveys, or stopping a vehicle at an interview station for vehicle intercept surveys. At this point, the potential respondent can immediately refuse to speak with the interviewer or else he or she could find out what the interviewer wants.

Figure 3.8 Process Diagram for an Example Personal Interview Survey

The interviewer introduces the study, and the respondent could agree or refuse to participate. For many studies, some respondents that agree to participate are not in the survey population of interest for one reason or another, so they need to be screened out. Screening questions can be as simple as: “Are you waiting for bus number 5?” or “Are you the head of the household?” or more complicated, such as a series of questions about the geography of a person’s current or recent trips. Depending on the respondent’s answer to the screening questions, the interviewer may terminate the interview. If the respondent is determined to be in the survey population of interest, then the interview would be conducted. At this point, the interview could be completed, or the respondent could break it off or refuse to answer the key questions that are needed for the responses to be usable.

Table 3.2 summarizes the most commonly cited positive and negative aspects of personally administered interviews when compared to other survey methods. The ways that these advantages and disadvantages affect particular travel surveys are discussed in later chapters.

Table 3.2 Personal Interviews

3.2.5 Self-Administered Surveys Distributed by Intercept Methods

A common variant to personal interviews in travel surveys is the personal distribution of self-administered surveys to respondents. The respondents are asked to complete the survey and to return it in some way, usually by mail or by dropping it in a conveniently located collection bin. Figure 3.9 shows an example of a survey process for this method. The intercept, recruitment, and screening of respondents is essentially the same as for the personal interview method, but rather than interviewing the respondent, the fieldworker simply hands them a questionnaire to complete without follow-up.

Figure 3.9 Process Diagram for an Example Intercept/Self-Administered Survey

A number of outcomes are possible: the respondent could complete the questionnaire and return it as requested, she or he could simply never return the questionnaire, or she or he could return the questionnaire in unusable condition. If a returned questionnaire is unusable but provides respondent address or telephone information, it might be possible to recontact the respondent for additional information to make the response usable.

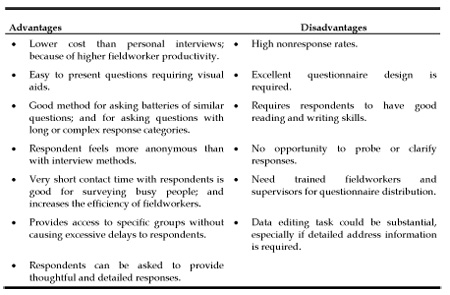

The advantages and disadvantages of this survey method with respect to other methods are summarized in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3 Self-Administered Surveys Distributed by Intercept Methods

3.2.6 Self-Administered Surveys Distributed to Groups

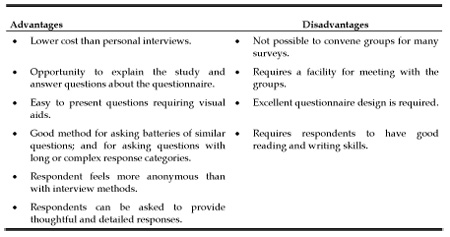

For some survey efforts, it is possible to assemble groups of respondents to complete self-administered surveys. This survey method seeks to combine the advantages of personal interview surveys, such as having the opportunity to explain the questionnaire and answer respondent questions, with the advantages of personally distributed self-administered surveys, including the ability to ask questions with long sets of response categories or questions that require extra response time. This survey method is sometimes used to survey hard-to-survey groups, including ethnic groups and special-interest groups. Table 3.4 describes the advantages and disadvantages of group surveys.

3.2.7 Telephone Interviews

In the past 15 years, the telephone interview survey has become an extremely popular surveying tool, both for transportation surveys and for other types, as well. As the cost of survey fieldwork has risen, telephone surveys have become more cost-effective (though less flexible in terms of content) than traditional in-home interviews. Telephone interviewers can contact several households in the time it takes a field interviewer to travel to one particular home, and telephone interviewers can be supervised much more effectively than field interviewers.

Telephone surveys are limited in that only households with land-line telephones can be contacted. Nationally, approximately 93 percent of households have telephones, but this percentage varies from city to city. Households without phones are more likely to be composed of ethnic minorities, be poorer, and have lower auto ownership rates than households with phones (Cohen et al., 1993). Since such households are likely to make fewer trips and are less likely to use an automobile for trips, telephone surveys may bias survey results to some degree. Additionally, in recent years there has been an increased prevalence in cellular telephone use. Many households have chosen to not have a land-line telephone, but prefer using their cellular as their primary source of telephone communication. As cellular telephone numbers are not as yet widely available in public directories, this trend raises additional questions about the validity of phone surveys and the potential for leaving out segments of the population.

There are ways to address the potential bias resulting from non-telephone households. If they can be identified, households without phones can be interviewed in person. Alternately, households which share demographic or other characteristics with non-telephone households can be oversampled. The U.S. Census Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) can be used to identify these characteristics.

There are two types of telephone surveys. In the first, a sample of telephone numbers is drawn from available telephone number lists (either published directories or lists from previous survey efforts). In the second type, the sample of numbers is drawn from a random list of numbers. This is known as a random-digit-dialing (RDD) survey.

Table 3.4 Self-Administered Surveys Distributed to Groups

Working off available telephone number lists or directories greatly enhances the likelihood that an attempted call will be to a working phone at a private residence, and in most cases allows the surveyor to know the address of the respondent before calling them (this is particularly useful for survey efforts with specific study areas or studies with geographic area quotas or targets). However, the rate of unlisted telephone numbers in the U.S. is high and increasing. Table 3.5 shows the percentage of households with telephones and the percentage of phone numbers that are unlisted for 100 metropolitan areas.

Table 3.5 Unlisted Rates of the Top MSA Markets for 1989

Many travel surveyors are willing to accept that a telephone survey will be unable to include five to 15 percent of the households in an area because the households have no phones (or use cellular telephones rather than land-lines), but most surveyors balk at the idea of excluding up to half the households in a region from a survey sampling frame. For this reason, RDD surveys are more commonly used in travel surveys than surveys with directories. Some travel surveyors have used a combination of the two approaches to maximize the efficiency of the listed approach, while compensating for the potential bias with RDD surveys.

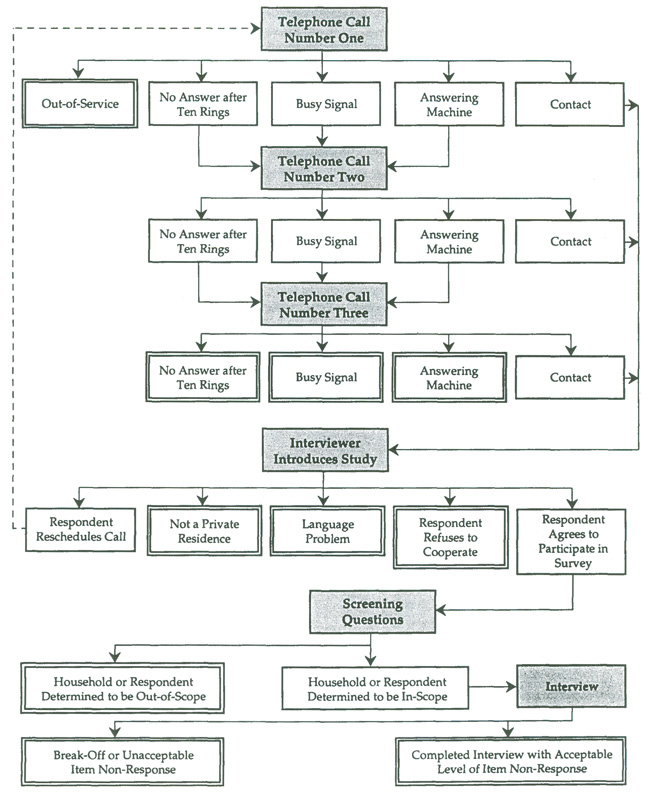

Regardless of whether a listed approach or an RDD approach (or a combination of the two) is adopted, the process for conducting individual telephone surveys is similar to that shown in Figure 3.10. The process diagram assumes that the telephone survey was designed with the following parameters:

· Up to three attempts will be made to a single telephone number (typical telephone travel surveys allow for between five and 10 attempts);

· Interviewers hang up if there is no answer after 10 rings; and

· Interviewers do not leave messages on answering machines.

The most common general methods used for surveying the public in the U.S. are:

· Personally administered interviews;

· Self-administered surveys distributed by intercept methods;

· Self-administered surveys distributed to groups;

· Telephone interviews; and

· Self-administered mail surveys.

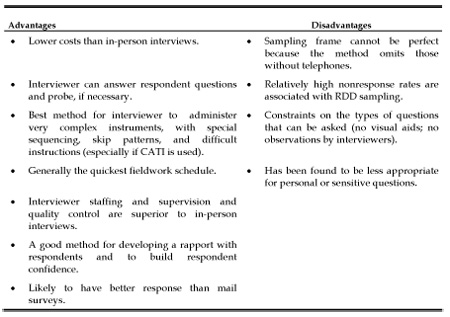

Table 3.6 discusses the key advantages and disadvantages of the telephone interview for travel surveys.

Figure 3.10 Process Diagram for an Example Telephone Survey

Table 3.6 Telephone Interviews

Each method has its strengths and weaknesses, and each is the optimal choice for certain circumstances. Some survey methods are more reasonable than others for certain travel survey types. This section outlines the steps of the different survey methods and discusses the advantages and disadvantages of each one.

3.2.8 Mail Surveys

Mail surveys are commonly used for travel surveys because of their low cost and resource requirements; and because of their simplicity. A mail survey in its most simple form requires obtaining a complete address list from a source, such as a utilities customer database, sending self-administered surveys to the households, and then simply waiting for replies. Travel surveyors have found that response levels can be enhanced through the use of pre-notification letters and follow-up letters and questionnaires.

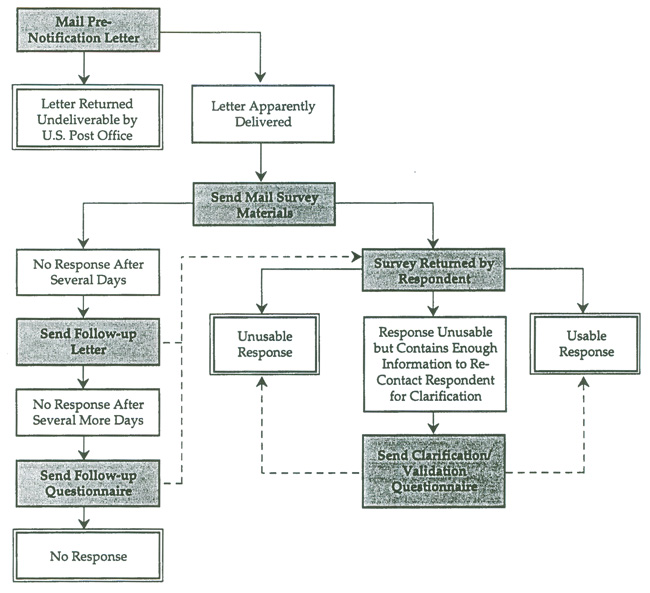

Figure 3.11 shows the process for an example mail survey. In this survey, a letter is sent to each potential respondent alerting them to the fact that they will be receiving a mail survey in a few days. Immediately following the letter, the surveying organization sends the mail survey to all the addresses, except those for which the prenotification letters were returned undeliverable. Once the survey materials have been sent, the surveyor simply waits for responses. After approximately seven days, households that have not responded are sent a follow-up letter reminding the respondents of the questionnaire, and after a few more days, those who still have not responded are re-sent the questionnaire.

Figure 3.11 Process Diagram for an Example Mail Survey

All the surveys that are returned by respondents are coded and reviewed. The surveyors then send letters requesting additional information from respondents whose questionnaires require clarification. Mail surveys can be difficult due to the higher rates of non-response experienced. For this reason, it is important that mail surveys over sample the frame in order to ensure adequate data collection.

Table 3.7 summarizes the positive and negative aspects of self-administered mail surveys.

3.2.9 Combinations of Survey Methods

In travel surveys, the basic survey methods are often used in combination with one another to try to capture the benefits of more than one method. For instance, the most common approaches for conducting household travel/activity surveys combine telephone and mail survey techniques. This can be done either by first conducting a mail survey and following up with a telephone call, or by identifying participatory households through a telephone survey and following up with a mail survey. Additionally, it is becoming more common for surveyors to first utilize a mail or telephone survey, followed up by an in person interview or "focus group" activity.

Figure 3.12 shows the survey methods that are generally used for the different travel surveys.

Table 3.7 Self-Administered Mail Surveys

Figure 3.12 Survey Methods Used for Different Travel Surveys

REFERENCES

Axhausen, K.W., Travel Diaries: An Annotated Catalogue, University of London Centre for Transport Studies Working Paper, November 1994.

I don’t have the photo editing software to divide this up picture properly to keep the title bar and cut the data list.

Table 3.5 (page 2)

Table 3.5 (page 3)