CHAPTER 4.0 MANAGEMENT AND QUALITY CONTROL

Note: Significant components of this chapter come from Chapter 4 of the FHWA Travel Survey Manual. Material has been reviewed and updated by Laurie Wargelin and Sudeshna Sen.

All travel surveys will be imperfect, but effective management and strict quality control procedures will greatly enhance the accuracy and validity of the survey results. This chapter briefly describes some of the management issues that are common to most survey types. Specific procedures for maintaining quality standards for each specific type of travel survey are described in the following chapters.

4.1 Travel Survey Quality; Quantity; and Resource Tradeoffs

Richardson, Ampt and Meyburg claim that:

“The essence of good survey design is being able to make tradeoffs between the competing demands of good design practice in several areas (such as sample design, instrument design, conduct of surveys, and data weighting and expansion) so as to arrive at the most cost-effective, high quality survey that meets the needs of the client within budget constraints” (Richardson, Ampt and Meyburg, 1995).

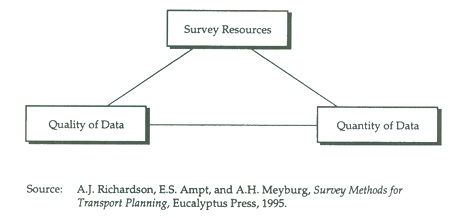

These authors make use of a concept called the “Architects Triangle”; as shown in Figure 4.1. In survey design, the quality and quantity of data and the cost of data collection are traded off against each other. The goal of survey designers is to produce the optimal mix of the three elements.

As the authors point out, survey budgets are generally set prior to the survey effort, so the survey team is usually in the position of making set investments in the quantity and quality of data. The quantity of data in surveys is a function of the number of survey respondents and the amount of information gathered per respondent. The quality of survey data is related to the selected survey method, the fieldwork procedures, instrument design, and the representativeness of the chosen sample. It is ineffective to collect as much information as possible to the exclusion of ensuring that the collected data are representative of the population. On the other hand, it is not usually possible to invest in expensive survey quality control procedures without decreasing sample size (and increasing the uncertainty of many parameter estimates).

Figure 4.1 Richardson’s, Ampt’s and Meyburg’s “Architect’s Triangle”

4.2 Maintaining Quality in the Travel Survey Process: Total Survey Design

Recognizing that the critical elements of the success of almost any survey implementation process are the preset resource (time, staff, and budget) limitations and the necessary tradeoffs between quality and quantity concerns, many surveyors endorse the concept of “total survey design” (Dillman, 1978). Total survey design is defined by two principles:

· Each task of the survey design and implementation is interrelated with all the other tasks, and design decisions made in one task need to be consistent with the decisions made in the other tasks.

· The overall usefulness of the survey effort is limited by the weakest element of the design. It is ineffective to invest large resources into one element of the survey if the same quality levels cannot be maintained in the other survey elements.

Dillman has developed these total survey design concepts into a detailed mail and telephone survey methodology. Many survey efforts have been based on Dillman’s specific approach, including travel surveys in Southeastern and Southwestern New Hampshire (Marshall et al., 1992). But regardless of whether these specific procedures are used, the basic principles of total survey design should apply to all travel survey design efforts.

Travel survey researchers have been known to spend several person-months developing, testing, and revising a survey instrument, only to have it fielded by poorly trained, unsupervised fieldworkers. Similarly, it is common for an agency to specify in an RFP (request for proposals) a low level of sampling error for a survey, but not set limits on any not so easily quantified sources of error, such as non-response.

This is not to recommend that one should simply give up on trying to produce high quality survey instruments or on demanding high levels of precision. Rather, total survey design means that the entire process and each of the many areas where errors and biases can creep into the design should always be considered.

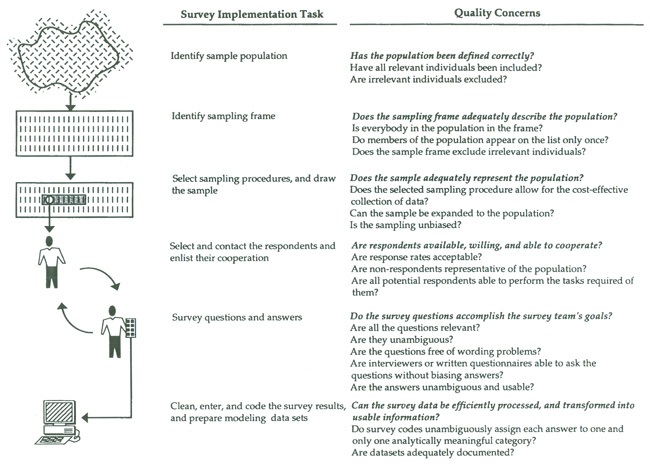

Figure 4.2 summarizes the many aspects of the survey implementation process that survey designers should consider. If each of the quality concern questions can be answered, “yes,” the survey effort is likely to be quite successful. More likely, the answer to many of the questions will be “I don’t know” or “no.” The challenge is to minimize the negative effects of these problems with the limited available resources. The survey team should determine the weak links in the implementation process, and if possible, divert resources to those areas. Considering all aspects of the implementation process together will help the survey team to avoid misspending resources on problems which are insignificant, in the greater scheme of things.

4.3 Management of Travel Surveys

The budgeting, staffing, oversight, scheduling, and coordination needs for each travel survey effort differ, but a few general recommendations can be made.

4.3.1 Survey Costs

Although travel survey costs are often reported, the total cost to an agency of conducting travel surveys is often quite difficult to calculate. Typical travel surveys are collaborative efforts between client agencies and contractors. The contractor cost can be calculated, but often the internal costs of an agency are not determined on a project-by-project basis. In addition, the division of labor between the client agencies and the contractors is different for every effort, so the cited costs often include different components. Often, when survey designers apply “rules-of-thumb” in budgeting survey efforts, they find their actual costs are quite different.

The best approach for predicting the costs of a proposed survey effort is to build it up from specific anticipated labor, facility, and material costs. Appendix A provides some simplified survey cost calculation worksheets for different types of surveys.

Figure 4.2 Travel Survey Quality Concerns

4.3.2 Managers and Supervisors of Fieldworkers

To a large extent, the management of a travel survey will depend upon the management environment of the sponsor agency. By now, many organizations have moved beyond rigid chains-of-command, so generalizing about the best organizational and management plans for a specific effort or diagramming the best organizational structure for a survey project is difficult.

However, regardless of the overall structure of the project, there are a number of key management tasks that need to be accomplished. First and foremost, the project will need a proactive hands-on Project Manager. This person will have the day-to-day responsibility for coordinating the activities of submanagers and for keeping the data collection effort on track to achieve the study objectives. Even if most of the survey work and data analysis will be performed by consultants, the sponsoring agency project manager should expect to spend a substantial portion of her or his time on the project. Almost invariably, even with careful planning, anticipated survey procedures and methods will need to be modified as the survey effort progresses.

The second key individual in a travel survey effort is the Survey Manager. Often, this person is the Project Manager for the survey contractor or an independent consultant specializing in survey research. This person will be responsible for all phases of the survey effort, with a particular emphasis on the specific data collection tasks. The Survey Manager will direct field supervisors and fieldworkers, and monitor the progress of the survey work on a continuing basis.

The third manager required in the survey effort is a Travel Demand Manager. Because the outputs of the travel survey project will be travel modeling data, it is extremely important that an individual or individuals with a strong sense of the impending modeling tasks be included in the survey design and implementation process. This person will be a key contributor to the design of the survey, the sampling, and the development of survey instruments, and it will be his or her responsibility to ensure that the survey effort produces the desired modeling inputs. In addition, this manager should have input into the data cleaning and coding tasks, and should direct the programming work. The Travel Demand Manager could be an agency staff member or a transportation planning consultant.

For smaller surveys, these managers need not be committed to the project full-time, but larger efforts will easily consume all of their time (and perhaps some Deputy Manager time, as well). For smaller efforts, the three management positions may be filled, theoretically, with one or two people, but this practice is not recommended for two reasons. First, there will be busy periods where the amount of work at particular critical points in the survey development will be overwhelming. Second, the quality of the survey effort will be enhanced by having more managers reviewing the ongoing work, especially if the managers are looking at the data collection effort from different perspectives as a Survey Research Manager and a Travel Demand Manager would.

Each specific survey task will require one or more field supervisor and several staff members to actually perform the work. Some of these workers may be able to work on more than one task if the tasks occur at different points in time, but generally it is better for staff members to become specialists in particular tasks. A major advantage of contracting the survey work to a specialist firm is the level of staff specialization that these firms can provide.

4.3.3 Oversight Committees, Peer Review Panels and Expert Advice

A number of recent survey efforts have relied upon advice and assistance from knowledgeable planners and surveyors not directly involved with the day-to-day survey development tasks. These outside experts can bring to the project:

· A wider breadth of experience than is available on the survey team;

· Relatively low-cost management consulting advice;

· A “Board of Directors” oversight function for the survey project;

· A sounding board for ideas and potential innovations; and

· A forum to resolve issues on which survey team managers disagree.

One of the most effective quality control mechanisms used in recent travel survey efforts has been the peer review panel, a group of survey and modeling experts that are convened at the key stages of the survey project

to provide advice and guidance to survey managers. Most recent peer review panels have consisted of:

· Key staff members from other MPOs with recent survey experience;

· University professors and consultants with expertise in transportation modeling and travel survey work; and

· State and Federal Department of Transportation staff members.

In addition, peer review panel members could also include:

· Staff members from the sponsoring agency that are not directly involved with the survey effort;

· Staff members from other local transportation agencies; and

· Survey researchers with experience outside of travel surveys.

In addition to, or instead of, the peer review panel, some recent travel survey sponsors have relied on one or more “consultant coaches” to assist with the survey planning and design work. These coaches are typically brought in early in the process to help perform preliminary planning tasks and to help the agency prepare to contract with one or more other consultants to perform the final survey design work and actual data collection.

The use of outside peer review panels and coaches can be cost-effective, because these individuals are used only at key decision points in the survey development process and because they are being asked primarily for advice, rather than for deliverable products.

4.3.4 Schedule

The planning and design of travel surveys can be quite time-consuming. Allocating adequate time for designing the overall survey, including time for resolving unexpected difficulties is essential. Managers of many recent travel survey efforts have found their original schedules to be infeasible once the detailed complexities of the design effort became apparent. Slippage in the design and implementation schedule can be especially damaging in travel surveys that are intended to be season-specific, because in these cases the inability to complete the fieldwork as planned causes a delay of a year before actually fielding the survey.

Therefore, as early as possible in the planning process, it is very important to prepare a realistic survey schedule which anticipates the inevitable difficulties that will occur. Because different agencies have very different funding mechanisms and consultant procurement processes, it is impossible to specify the amount of time needed to fully plan and implement a travel survey, but for large efforts, such as household travel surveys, it is not uncommon for agencies to begin the preliminary planning process one year to 18 months in advance of the fieldwork.

Because even simple travel surveys have many interrelated and parallel tasks, use of computerized CPM or PERT scheduling techniques is recommended. These methods allow the survey team to identify the key milestones in the design and implementation process, as well as crucial deadlines.

4.3.5 Coordination

Many agencies and private companies can be involved in travel surveys in a particular region or state. Agencies should maintain channels of communication with all relevant organizations from the inception of any survey effort. This is especially true if more than one agency will be sponsoring travel survey work. Travel demand modelers from the separate agencies will be able to use the survey data much more effectively if the survey efforts are coordinated.

At the beginning of the survey effort, the sponsoring agency should contact:

· All affected state agencies;

· Local and regional planning officials;

· Local and regional elected officials;

· Local and state police;

· Federal agencies that may be involved;

· Local transit providers;

· Active public interest groups; and

· Chambers of commerce/business groups (for workplace/establishment surveys).

In addition, the sponsoring agency may want to consider contacting the news media if the advance publicity is felt to be important. Alerting the media of the survey effort may increase the level of cooperation, reduce the number of complaints about the survey, and head off any potential negative press once the survey effort is undertaken. Coordination issues for each survey type are discussed further in the following chapters.

4.4 Ethical Issues in Travel Surveying

Managers of travel surveys and surveying and demand modeling contractors should be aware that they have a number of ethical (and legal) responsibilities to each other, to their staff, and most importantly, to respondents and potential respondents.

4.4.1 Responsibilities of Agencies and Contractors to Each Other

The responsibilities of planning agencies and contractors to one another should be described as clearly as possible in a formal contract. Both parties should have a clear understanding of their responsibilities under the agreement and those of the other party prior to any work being conducted. Potential problems (and potential remedies) should be identified, and the responsibilities of each party under various outcomes should be assigned.

4.4.2 Responsibilities to Fieldworkers

The agency or firm conducting the survey has certain obligations to the survey fieldworkers, including:

· Providing the basic employer obligations for the state and region;

· Adequately preparing fieldworkers for the survey effort by explaining the effort and their responsibilities to them; and

· Dealing with fieldworkers’ safety-related and personal security-related concerns.

The first obligation is straightforward, and requires little explanation. The need to adequately prepare fieldworkers for the survey effort is important to the analyst because of the potential for incomplete or incorrect data, but it is also important to fieldworkers. Fieldworkers should have a clear idea of their and fellow workers’ and supervisors’ responsibilities so that the potential for conflicts is minimized. In addition, fieldworkers may be put in the position of describing the survey goals and procedures to potential respondents or to police officers or other interested parties. Fieldworkers should not have to worry that they might have to provide deceptive, misleading, or inaccurate information.

The third general obligation to fieldworkers is especially important in travel surveys where fieldworkers are often asked to interact with moving vehicles or to spend time in and around high crime locations. The agency or firm conducting surveys must respect fieldworkers’ assessments of the safety and security of the planned survey procedures, and should be willing to take added steps to allay the fieldworkers’ concerns. In this respect, we offer the following guidelines:

1. Fieldworkers should be told explicitly that the job does not require them to go somewhere under circumstances that they feel are unsafe. Forcing fieldworkers into situations with which they are uncomfortable is likely to be unproductive in any case because if the fieldworkers are overly concerned about their safety or personal security, they will not do their best jobs. Reasonable precautionary measures, such as additional traffic control for roadside surveys and providing interviewer escorts for transit onboard surveys and home interview surveys, should be reviewed with fieldworkers and supervisors.

2. Fieldworkers should be briefed (and rebriefed) on safety procedures and on sensible procedures for reducing the risk of crime.

3. Fieldworkers should be allowed to visit survey sites prior to deciding whether the safety and security procedures are adequate. Doing so may allow fieldworkers to more easily object to the proposed work, but from the survey management viewpoint it is far better to have the concerns voiced before the day of the actual survey work.

Ideally, the survey agency or firm will be able to make modifications to the proposed survey procedures that address any fieldworker concerns about safety and security. If reasonable modifications are not successful in reducing the level of concern in a fieldworker, the fieldworker should be replaced. If at all possible, the agency or firm should make an effort to re-assign the fieldworker to a different task. In such cases it is imperative that the survey manager advise any potential replacement fieldworkers of the specific safety and security concerns of the original worker.

4.4.3 Responsibilities to Respondents and Potential Respondents

Travel surveyors must take steps to ensure that respondents are not deceived, that respondents’ privacy rights are not abused, and that the standard social research protections for participants are maintained. The most often cited types of deception with surveys are the use of survey techniques to disguise sales efforts and the use of survey techniques in campaigns to collect names and addresses for direct marketing firms. Fortunately, travel surveys are not typically subject to these types of deception because the sponsoring agencies usually are not trying to sell products or services.

It is generally acknowledged that these types of sales activities are detrimental to the survey field, and should be condemned, but other questionable survey activities often escape criticism. Well-meaning survey managers can easily violate the rights of respondents in an effort to maximize the amount of useful data from the survey. Common problems are (Aaker and Day, 1990)(Akaah and Riordan, 1989):

· Failing to provide the respondent with information about the sponsorship of the study;

· Failing to provide the respondent with information about the contracting firm conducting the survey;

· Misleading respondents about the time needed for the survey;

· Providing respondents with inaccurate information about gift or monetary incentives;

· Failing to tell respondents about potential follow-up surveys;

· Using techniques to observe or identify respondents without their knowledge (such as hidden tape recorders in telephone interviews, one-way mirrors, and ultraviolet ink identification codes on seemingly anonymous mail surveys);

· Failing to take steps to ensure that privacy is maintained throughout the survey analysis; and

· Careless storage and/or disposal of returned questionnaires.

To avoid these problems, Fowler suggests that all survey respondents be provided with the following information before being asked any questions:

1. The name of the organization carrying out the research, and for intercept and telephone surveys, the interviewer’s name.

2. The sponsor of the study.

3. An accurate, though brief description of the purposes of the research.

4. An accurate statement of the extent to which answers are protected with respect to confidentiality, bearing in mind that some states may not allow agencies to protect respondents’ confidentiality as much as other states do.

5. Assurance that cooperation is voluntary, and that no negative consequences will result to those who decide not to participate.

6. Assurance that respondents can skip any questions they do not wish to answer.

Today’s travel surveys generally provide the first four pieces of information, but only a few surveys explicitly provide the fifth and the sixth due to the fear among surveyors that these assurances invite non-response and due to the fact that most respondents will be familiar enough with surveys to understand that they have the right to refuse to answer all or certain questions. If the suggested guidelines are not explicitly followed, interviewers should, at a minimum, be instructed to accept refusals (and item-related refusals) without question and not to push respondents into revealing information which they are uncomfortable providing.

Protecting respondents’ privacy is an increasingly important issue for travel surveys. Some surveys ask respondents to provide work schedules for all household members, travel times and school locations for young children, specific home and work addresses, and detailed vehicle data, among other information. Because these data could easily be used against the respondents, it is incumbent upon the surveying firm or agency to safeguard the data.

Travel survey data and returned forms should be treated as confidential business information by those who collect and analyze them. Fowler suggests that the following precautions be used (Fowler, 1988):

1. All people who have access to the data or a role in the data collection should be committed in writing to confidentiality.

2. Links between answers and identifiers should be minimized. Analyses not requiring names and addresses should be performed on datasets without these pieces of information.

3. Completed interview schedules and returned questionnaires should not be accessible to people outside the project team.

4. Identifiers should be removed from completed questionnaires if they are made available to people outside the survey team.

5. Individuals who could identify respondents from their profile of answers, such as supervisors in the case of a survey of employees, should not be permitted to see the actual questionnaire responses.

6. The link between identification numbers and sample addresses and telephone numbers in data files should be minimized.

7. During analysis, researchers should be careful about presenting data for very small categories of people who might be identifiable.

8. Upon completion of the modeling work, the project manager is responsible for seeing that the completed instruments are destroyed or are securely stored on a continuing basis.

REFERENCES